Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Prev Med Public Health > Volume 57(3); 2024 > Article

-

Original Article

Classification of Healthy Family Indicators in Indonesia Based on a K-means Cluster Analysis -

Herti Maryani1

, Anissa Rizkianti1

, Anissa Rizkianti1 , Nailul Izza2

, Nailul Izza2

-

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2024;57(3):234-241.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.23.497

Published online: May 5, 2024

- 1,197 Views

- 107 Download

1Research Center for Population, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta, Indonesia

2Research Center for Public Health and Nutrition, National Research and Innovation Agency, Surabaya, Indonesia

- Corresponding author: Herti Maryani, Research Center for Population, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jl. Jend. Gatot Subroto 10, Jakarta 12710, Indonesia E-mail: hert001@brin.go.id

Copyright © 2024 The Korean Society for Preventive Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Objectives:

- Health development is a key element of national development. The goal of improving health development at the societal level will be readily achieved if it is directed from the smallest social unit, namely the family. This was the goal of the Healthy Indonesia Program with a Family Approach. The objective of the study was to analyze variables of family health indicators across all provinces in Indonesia to identify provincial disparities based on the status of healthy families.

-

Methods:

- This study examined secondary data for 2021 from the Indonesia Health Profile, provided by the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia, and from the 2021 welfare statistics by Statistics Indonesia (BPS). From these sources, we identified 10 variables for analysis using the k-means method, a non-hierarchical method of cluster analysis.

-

Results:

- The results of the cluster analysis of healthy family indicators yielded 5 clusters. In general, cluster 1 (Papua and West Papua Provinces) had the lowest average achievements for healthy family indicators, while cluster 5 (Jakarta Province) had the highest indicator scores.

-

Conclusions:

- In Indonesia, disparities in healthy family indicators persist. Nutrition, maternal health, and child health are among the indicators that require government attention.

- The goal of health development is to raise everyone’s public awareness, willingness, and ability to live healthily in order to achieve the highest level of public health. This goal is achievable if health development begins with the family unit [1]. A family approach allows the in-depth mapping of health problems through home visits. The Healthy Indonesia Program with a Family Approach (HIPFA, also known as PIS-PK) was founded from this initiative.

- The implementation of PIS-PK aimed to improve family access to comprehensive health services, including promotive and preventive services as well as basic curative and rehabilitative services. PIS-PK supported the attainment of district/city minimum service standards and national health insurance, as well as the goals of the Healthy Indonesia Program. According to Ministry of Health Regulation (Permenkes) Number 39 of 2016, to measure family health status, the Ministry established 12 major indicators, grouped into 3 categories: maternal and child health, communicable and non-communicable diseases, and health behavior [2]. The more indicators a family could fulfill, the closer it would be to meeting the criteria for a healthy family. As a result, the level of public health in that region would also be higher.

- A 2013 study on basic health research (Riskesdas) used the concept of healthy family indicators to evaluate residents’ health status in different regions and prioritize health problems requiring intervention [3]. The indicators derived from the collection of family data have also been used by public health centers (Puskesmas) in preparing proposed activity plans and were included in the routine Puskesmas report [4]. Though the indicators have been an important component in the process of planning and evaluating regional health programs, indicator values have not been evenly distributed across Indonesia. Several studies have found that a regional disparity persists, particularly in the provinces of Papua and West Papua when compared to other provinces in the islands of Java-Bali, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi [5,6].

- To improve how program priorities are determined for each region in Indonesia, we analyzed healthy family indicators according to regional classifications. This process determined which provinces had poor health quality and would require immediate interventions.

- The objective of the current study was to analyze variables of family health indicators across all provinces in Indonesia and identify provincial disparities in the health status of resident families. The results may be useful as a reference for the government in policy-making to improve the health status of communities through family units and to advocate for increasing the health budget in each province.

INTRODUCTION

- This study examined secondary data for 2021 from the Indonesia Health Profile, provided by the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia [7], and from the 2021 welfare statistics by Statistics Indonesia (BPS) [8]. Cluster analysis, a multivariate method of grouping objects according to their characteristics, was applied to the data. Within a cluster, objects have a relatively homogeneous level of similarity, while their characteristics are markedly different or heterogeneous compared to other clusters.

- The 2 main approaches for cluster analysis involve hierarchical and non-hierarchical methods. This study employed a nonhierarchical method for classifying objects, in which the number of clusters to be formed was predetermined. This non-hierarchical approach has the advantage of analyzing larger samples more efficiently, and it has only a few flaws regarding outlier data, distance measures, and irrelevant or imprecise variables. The k-means algorithm, a frequently employed cluster analysis technique, was used to determine a temporary cluster center that was updated until termination criteria were met. For optimal cluster analysis results, the researchers compared the output of non-hierarchical methods (k-means) and hierarchical methods such as complete linkage, which was used to measure the distance between clusters relative to the farthest object. For the current study, clusters of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 were formed. The optimal number of clusters was determined using the pseudo F-statistics criterion. In addition, the researchers calculated the internal cluster dispersion (ICD) rate to determine the optimal cluster analysis technique.

- Health family indicators are used to determine whether a family is deemed healthy or not. The Healthy Indonesia Program considered 12 primary indicators for determining a family’s health status, including nutritional program indicators for maternal and child health, indicators for the control of communicable and non-communicable diseases, and indicators for behavior and environmental health. Table 1 describes the 10 variables that were analyzed.

- Ethics Statement

- Permission to use the dataset was obtained from the Ministry of Health. Since this study was a secondary analysis of the Indonesia Health Profile and individual considerations such as names and addresses were not included, the ethical approval was not required.

METHODS

- Characteristics of Healthy Family Indicators

- Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the family health indicators across Indonesia. Participation in the National Health Insurance program had the highest average compared to the other indicators, and the use of family planning methods had the lowest average value.

- The large variance values in this analysis arose from the wide data distribution and significant deviations from the mean. For instance, the variance of the X3 indicator (monitoring toddler growth) was 297.94, with a mean of 62.30%. This variance included provinces with values as low as 2.10%, which are considerably below the average. The significant disparity in average values among provinces contributed to the large variance values.

- The researchers compared hierarchical and non-hierarchical analytical approaches to determine the best clustering technique. By using pseudo F-statistics criteria, we calculated the optimal number of clusters between 2 and 6. Table 3 shows the results of the analysis, indicating that 5 was the optimal number of clusters, with the highest k-means value (15.1931). We determined that cluster analysis using the non-hierarchical method (k-means) was superior because the pseudo F-value was greater than in the hierarchical method.

- The next step in determining the appropriate clustering method was to examine the ICD rate, which quantifies the level of dispersion within a cluster. Lower ICD values reflect better grouping results. The ICD rate of the hierarchical method was 0.3411, and that of the non-hierarchical method was 0.3230. The non-hierarchical k-means method had a lower ICD rate than the hierarchical method, meaning that the k-means method performed better in classifying Indonesia’s 34 provinces based on healthy family indicators.

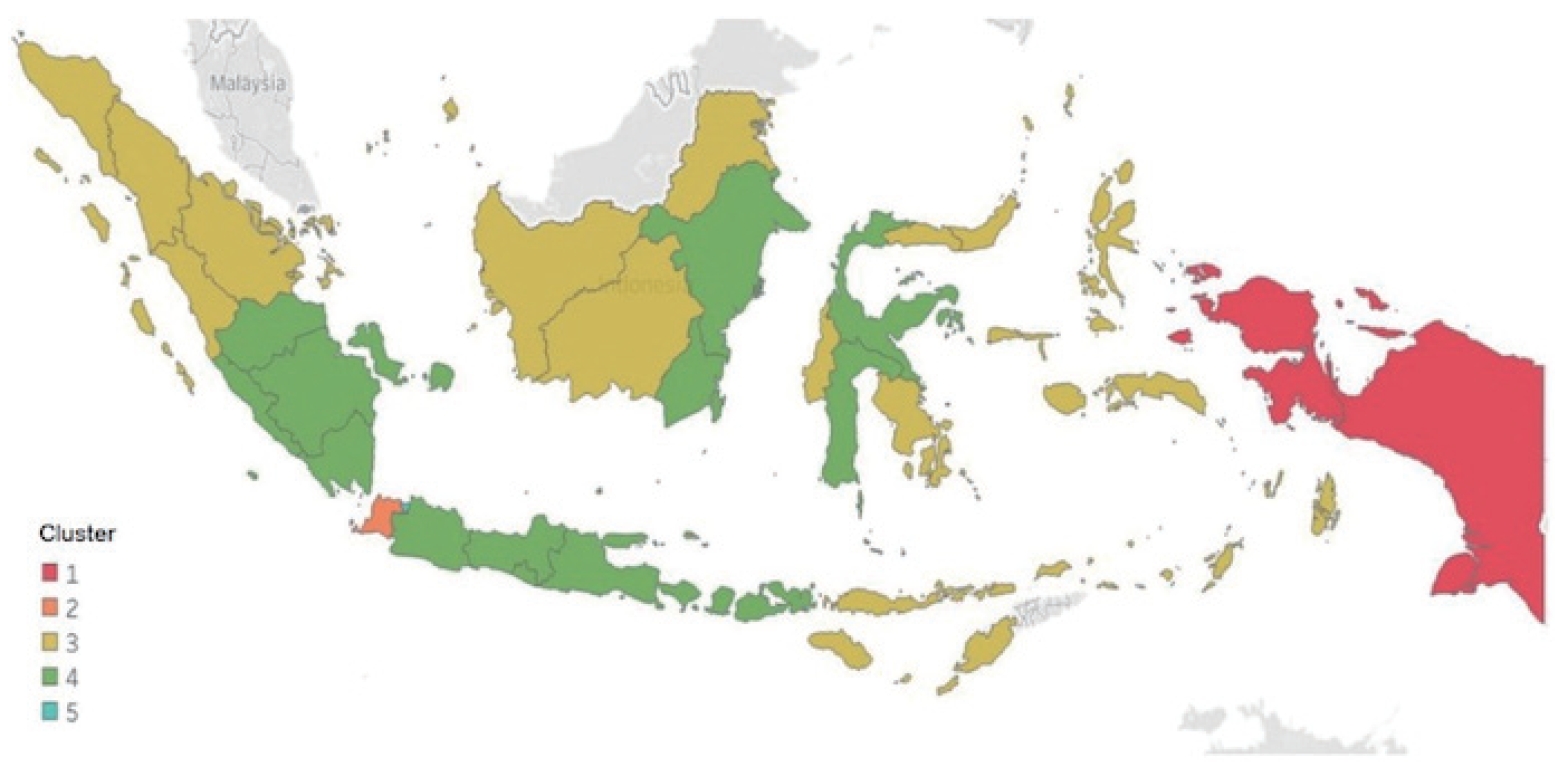

- Figure 1 displays the results of k-means cluster analysis, along with the number of cluster members. Cluster 1 contained 2 provinces, clusters 2 and 5 had 1 member province each, and clusters 3 and 4 had 15 provinces each. The provinces corresponding to cluster 1 represented the eastern region of Indonesia, specifically the Papua and West Papua provinces. These 2 provinces exhibited the lowest healthy family indicator scores in comparison to the other clusters. The provinces located on the islands of Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi were categorized into clusters 3 and 4, exhibiting comparable achievement scores for healthy family indicators. However, variations existed among these scores in terms of toddler growth, exclusive breastfeeding, and basic immunization. Aside from the provinces of Banten and DKI Jakarta, the majority of provinces located on the island of Java were included in a single cluster.

- Cluster Interpretation

- Table 4 shows the average values of each cluster’s healthy family indicators. Cluster 1 had the lowest average scores for healthy families in 6 indicators, whereas it had the highest average value for the X1 indicator (family planning methods). The mean values varied in cluster 2, such that it had the highest average score for 3 indicators and the lowest average score for the X6 indicator (sanitation access).

- Clusters 3 and 4 shared similar characteristics, except for a few indicators with higher average values in cluster 4. Cluster 4 also had the lowest average score among clusters for the X1 indicator.

- In comparison to the other clusters, cluster 5 members had the highest healthy family indicator scores overall. The majority of the indicators in cluster 5 had the highest averages; of the 10 indicators analyzed, 6 of them had the highest average value.

RESULTS

- Our analysis found disparities across provinces in the indicators for nutrition, maternal health, and child health. West Papua and Papua (cluster 1), for example, had the lowest average coverage, which means that the Papua region requires massive development in all aspects of healthy family indicators. In general, children in Papua typically encounter challenges in various aspects of their development, including language acquisition, fine motor skills, adaptive behavior, personal-social interactions, and gross motor abilities [9]. It has been shown that the monitoring of young children’s growth and development in Papua remained poor, influenced by various external factors, including the physical environment, social environment, and maternal upbringing [9]. In addition, Papuan children in the midland and mountainous terrain areas are more likely to have inadequate nutrition [10].

- Poor access and inadequate provision of healthcare services could have accounted for the disparities in this region. The unfavorable geographical conditions exacerbate the challenges, particularly in the eastern region of Indonesia [11]. In Ghana, geographical discrepancies have contributed to the lower coverage for a continuum of care among poor women and children [12]. Similarly, disparities in monitoring child growth are more consistent within and across geographical regions in Africa [13].

- Inadequate hygiene practices due to a lack of sanitation and clean water could also have contributed to lower average coverage of healthy family indicators, particularly in cluster 2, representing Banten Province. This association is supported by the fact that 15% of households in Banten currently lack access to sanitary latrines. Persistent disparities in access to proper sanitation facilities result in inadequate hygiene practices [14]. Proper sanitation facilities, such as toilets and latrines, are essential for maintaining good health because they allow people to dispose of their waste appropriately, preventing the contamination of their environment and reducing the risk of diarrhea and other infections. Moreover, people with lower levels of formal education are more likely to defecate openly and show a reluctance to construct and maintain hygienic latrines, due to a lack of necessary knowledge and awareness about proper sanitation practices [15].

- Another important finding was that cluster 4, containing the regions of Java, Bali, Nusa Tenggara, Sumatra, and Sulawesi, had a lower rate of utilization of family planning contraceptives than other clusters. It has been demonstrated that attitudes towards family planning were a strong predictor for the low uptake of contraceptive methods in these regions. Having more children is generally seen as a parental investment because many Indonesian parents remain committed to the old local proverb, “Banyak anak, banyak rejeki” (“more children mean more blessings and luck”) [16]. In addition, the use of contraception was significantly lower among couples intending to have more children, having a lack of awareness of family planning, showing more limited decision-making processes, and having limited access to desired contraceptive methods [17]. Recently, the family planning program has become less rigorously observed, although the implementation has been considered successful for more than 50 years [18].

- The study’s findings support the ongoing importance of knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about contraceptive use in Indonesia. Despite the low utilization of long-term methods of contraception, this method has been identified as a viable approach to reducing the number of pregnancies [19]. In South Sumatra, promotional activities by health cadres have affected the use of long-term reversible contraception (LARC) [20]. Other significant predictors for the use of LARC methods included age, educational level, and access to family planning services, as reported in East Java [21].

- The results of this analysis are in line with several studies in Indonesia showing that inequality has been identified as a key constraint in healthcare. Jakarta, as the largest metropolitan city in Indonesia, has a more developed healthcare system [22]. In this study, Jakarta (cluster 5) had the most noteworthy achievements for all indicators, including delivery of care in health facilities. As noted in previous studies, there are more obstetrics and gynecology specialists and hospitals per capita in Jakarta than in other regions of Java [23], and these institutions are supported by a well-developed health infrastructure [24].

- Though the government strives for the highest possible standard of health for all women in the country, disparities persist. Inequities may occur in the provision of delivery services within healthcare facilities as a consequence of disparities in health development [23,25]. To reduce this gap, the government has promoted the expansion of health insurance coverage, which was found to have a positive association with improving equitable access to maternal healthcare services in Indonesia [26]. Previous studies have shown that women with health insurance coverage were more likely to use antenatal care (ANC) [27,28]. Other factors, such as educational level, number of children, place of residence, and distance to healthcare facilities, were also found to be predictors of ANC utilization [29,30]. Furthermore, women from ethnic minorities and disadvantaged groups were less likely to use maternal healthcare services, including ANC visits [31,32].

- Apart from social protection programs, the decentralization of health services to the districts does not appear to have improved the range of services available to many Indonesians, especially in the eastern regions. Multiple programs designed to expand access to maternal and child healthcare services, water, and sanitation still have not reached many households across the country. Increasing the health budget may not be sufficient in itself to address the problem [33]. Therefore, more emphasis should be placed on cultural barriers, geographical barriers, and the development of the healthcare workforce in disadvantaged areas. Midwives, for example, have a potential role in improving maternal health, since they are more accessible to the community and have good compliance to standard ANC practices [34].

- Given that the family unit plays a significant role in shaping, maintaining, and restoring the health of individual residents, the concept of a healthy family should be evocative and improve the empowerment of family and community. The main social functions of the family have been characterized as religion, social culture, love and affection, protection, reproduction, socialization and education, economy, and environmental development [35]. A family-centered approach will facilitate needs-based healthcare and provide viable and long-lasting solutions [36].

- This study has a few limitations. Our analysis may help us to understand the existing disparities in health indicators across Indonesia, although the results are considered superficial. The substantial variations in aggregated data at the district level should be interpreted with caution, however. Further research should improve how indicators are assessed and conduct a more in-depth analysis to detect the causes of disparity. Due to the availability of secondary data, researchers were restricted to analyzing only 10 of the 12 family health indicators. Two variables were not considered: the adherence of hypertension patients to their prescribed medication and the availability of treatment for mental disorders.

- In conclusion, the implementation of the k-means method for cluster analysis provided better results in the classification of Indonesian provinces based on healthy family indicators. As the indicators for nutrition, maternal health, and child health require attention to improve health status within the family unit, it can be suggested that the government consider using indicator scores to prioritize provinces and improve the effectiveness of the PIS-PK program optimization. Further, it is imperative for the Ministry of Health to allocate more resources to the regions exhibiting significantly low levels of healthy family indicators.

DISCUSSION

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

-

Funding

None.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Maryani H. Data curation: Rizkianti A. Formal analysis: Maryani H, Izza N. Funding acquisition: None. Visualization: Maryani H, Izza N. Writing – original draft: Maryani H, Rizkianti A, Izza N. Writing – review & editing: Maryani H, Rizkianti A, Izza N.

Notes

Acknowledgements

| No. of clusters | Hierarchical (complete linkage) | Non-hierarchical (k-means) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 13.5365 | 13.5365 |

| 3 | 12.4696 | 12.4696 |

| 4 | 13.0348 | 13.0348 |

| 5 | 14.0023 | 15.1931 |

| 6 | 13.1418 | 14.6858 |

- 1. Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. Healthy families make Indonesia healthy; 2017 [cited 2024 May 22]. Available from: https://kesmas.kemkes.go.id/assets/uploads/contents/others/Warta-Kesmas-Edisi-03-2017_955.pdf (Indonesian)

- 2. Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. General guidelines for healthy Indonesia program with a family approach: regulation of the minister of health number 39 of 2016 Indonesia; 2016 [cited 2024 May 22]. Available from: https://dinkes.jatimprov.go.id/userfile/dokumen/Buku_Pedoman_PIS_PK.pdf (Indonesian)

- 3. Tjandrarini DH, Dharmayanti I. Achieving healthy indonesia through public health development index and healthy family index approach. Bull Health Syst Res 2018;21(2):90-96. (Indonesian). https://doi.org/10.22435/hsr.v21i2.314.90-96Article

- 4. Murnita R, Prasetyowati A. Analysis of the healthy family index to support health promotion programs. J Indones Health Manag 2021;9(1):1-13. (Indonesian). https://doi.org/10.14710/jmki.9.1.2021.1-13Article

- 5. Nur I, Fitriana L. Grouping provinces in Indonesia based on indicators of healthy families using hierarchical and non hierarchical cluster methods. 2021;2(1):27-36. (Indonesian)

- 6. Maryani H, Kristiana L, Paramita A, Izza N. Disparity of health development in Indonesia based on healthy family indicators using cluster analysis. Bull Health Syst Res 2020;23(1):18-27. (Indonesian). https://doi.org/10.22435/hsr.v23i1.2622Article

- 7. Ministry of Health of Republic Indonesia. Indonesia health profile in 2021; 2022 [cited 2022 May 2]. Available from: https://www.kemkes.go.id/id/profil-kesehatan-indonesia-2021(Indonesian)

- 8. Statistics Indonesia (BPS). Welfare statistics 2021 [cited 2022 May 2]. Available from: https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2021/11/19/36c2f9b45f70890edb18943d/statistik-kesejahteraan-rakyat-2021.html (Indonesian)

- 9. Manongga SP, Littik S. Structural model of Papuan children’s quality of life in different ecosystem zones in Papua. Indones J Multidiscip Sci 2023;2(4):2294-309. https://doi.org/10.55324/ijoms.v2i4.421Article

- 10. Manongga SP, Yutomo L. Determinant factors of malnutrition in Papuan children under five years: structural equation model analysis. Indones J Multidiscip Sci 2023;2(5):2379-2394. https://doi.org/10.55324/ijoms.v2i5.355Article

- 11. Megatsari H, Laksono AD, Ridlo IA, Yoto M, Azizah AN. Community perspective about health services access. Bull Health Syst Res 2018;21(4):247-253. https://doi.org/10.22435/hsr.v21i4.231Article

- 12. Shibanuma A, Yeji F, Okawa S, Mahama E, Kikuchi K, Narh C, et al. The coverage of continuum of care in maternal, newborn and child health: a cross-sectional study of woman-child pairs in Ghana. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(4):e000786. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000786ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Osgood-Zimmerman A, Millear AI, Stubbs RW, Shields C, Pickering BV, Earl L, et al. Mapping child growth failure in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 2018;555(7694):41-47. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25760ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Paramasatya A, Wulandari RA. Correlation of access to sanitation and access to drinking water stunting incidence in toddlers in the region of Serang District in 2022. Jambura J Health Sci Res 2023;5(2):695-706. https://doi.org/10.35971/jjhsr.v5i2.19145Article

- 15. Kosasih AL, Indiani D. Determinants of ownership of healthy latrines in Banten (data analysis from SDKI 2017). Media Nutr Public Health 2022;11(1):102-107. (Indonesian). https://doi.org/10.20473/mgk.v11i1.2022.102-107Article

- 16. Soseco T. Lessons from COVID-19: small and financially strong family. J Popul Indones 2020;49-52. https://doi.org/10.14203/jki.v0i0.577Article

- 17. Saputra W, Saputra D. Efforts to increase active participants of family planning in order to achieve the target of BKKBN strategic plan 2015-2019 in Musi Rawas Regency, South Sumatera Province. J Popul 2018;26(1):3-50. (Indonesian). https://doi.org/10.22146/jp.38688Article

- 18. Idris U, Frank SA, Hindom RF, Nurung J. Family planning (KB) practices and the impact on Papuan women reproductive health. Gac Sanit 2021;35 Suppl 2: S479-S482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2021.10.076ArticlePubMed

- 19. Center for Health Research University of Indonesia. Centre for health research. study of patterns of contraceptive use in East Java Province; 2020 [cited 2024 May 20]. Available from: https://chr.ui.ac.id/archives/7615 (Indonesian)

- 20. Wasilah S, Noor MS, Putri AO, Kasmawardah I, Abdurrahman MH. Training on information communication and family planning education for posyandu cadres to increase the attainment of long-term contraceptive methods in wetland areas. J Adv Community Serv 2022;6(4):1920-1924. (Indonesian). https://doi.org/10.31764/jpmb.v6i4.11657Article

- 21. Purbaningrum P, Hariastuti I, Wibowo A. Factor analysis of the low use of intra uterine device (IUD) contraception in East Java in 2015. J Biom Popul 2019;8(1):52-61. (Indonesian). https://doi.org/10.20473/jbk.v8i1.2019.52-61Article

- 22. Sokang YA, Westmaas AH, Kok G. Jakartans’ perceptions of health care services. Front Public Health 2019;7: 277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00277ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Laksono AD, Sandra C. Ecological analysis of healthcare childbirth in Indonesia. Bull Health Syst Res 2020;23(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.22435/hsr.v23i1.2323Article

- 24. Setyonaluri D, Aninditya F. Demographic transition and epidemiology: demand for health services in Indonesia; 2019 [cited 2024 May 22]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Diahhadi-Setyonaluri/publication/342697972_Kajian_Sektor_Kesehatan_Transisi_Demografi_dan_Epidemiologi_Permintaan_Pelayanan_Kesehatan_di_Indonesia/links/5f017c6092851c52d619b6f0/Kajian-Sektor-KesehatanTransisi-Demografi-dan-Epidemiologi-Permintaan-Pelayanan-Kesehatan-di-Indonesia.pdf (Indonesian)

- 25. Laksono AD, Wulandari RD, Soedirham O. Regional disparities of health center utilization in rural Indonesia. Malays J Public Health Med 2019;19(1):158-166. https://doi.org/10.37268/mjphm/vol.19/no.1/art.48Article

- 26. Anindya K, Lee JT, McPake B, Wilopo SA, Millett C, Carvalho N. Impact of Indonesia’s national health insurance scheme on inequality in access to maternal health services: a propensity score matched analysis. J Glob Health 2020;10(1):010429. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010429ArticlePubMedPMC

- 27. Laksono AD, Rukmini R, Wulandari RD. Regional disparities in antenatal care utilization in Indonesia. PLoS One 2020;15(2):e0224006. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224006ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. Wang W, Temsah G, Mallick L. The impact of health insurance on maternal health care utilization: evidence from Ghana, Indonesia and Rwanda. Health Policy Plan 2017;32(3):366-375. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw135ArticlePubMed

- 29. Yang Y, Yu M. Disparities and determinants of maternal health services utilization among women in poverty-stricken rural areas of China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023;23(1):115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05434-7ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Daka DW, Woldie M, Ergiba MS, Sori BK, Bayisa DA, Amente AB, et al. Inequities in the uptake of reproductive and maternal health services in the biggest regional state of Ethiopia: too far from “leaving no one behind”. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2020;12: 595-607. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S269955ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Bango M, Ghosh S. Social and regional disparities in utilization of maternal and child healthcare services in India: a study of the post-national health mission period. Front Pediatr 2022;10: 895033. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.895033ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Yan C, Tadadej C, Chamroonsawasdi K, Chansatitporn N, Sung JF. Ethnic disparities in utilization of maternal and child health services in rural Southwest China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(22):8610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228610ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Booth A, Purnagunawan RM, Satriawan E. Towards a healthy Indonesia? Bull Indones Econ Stud 2019;55(2):133-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2019.1639509Article

- 34. Paramita A, Andarwati P, Izza N, Kristiana L, Maryani H, Tjandrarini DH. Pregnant women’s preference for antenatal care (ANC) provider: lessons learned to support maternal mortality rate reduction strategies. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2022;53(Suppl 2):254-272. (Indonesian)

- 35. BKKBN. National family planning coordination board performance report (BKKBN) Tahun 2021; 2022 [cited 2024 May 22]. Available from: https://e-ppid.bkkbn.go.id/assets/uploads/files/e90c8-lk-bkkbn-ta-2021-audited_ttd.pdf (Indonesian)

- 36. Ninawati , Sulaeman ES, Tamtomo D. Implementation of context input process product model on healthy indonesia program policy with a family approach. J Health Policy Manag 2022;7(1):34-45. https://doi.org/10.26911/thejhpm.2022.07.01.04Article

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KSPM

KSPM

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite