Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Prev Med Public Health > Volume 57(3); 2024 > Article

-

Systematic Review

Coping Mechanisms Utilized by Individuals With Drug Addiction in Overcoming Challenges During the Recovery Process: A Qualitative Meta-synthesis -

Agus Setiawan1

, Junaiti Sahar1

, Junaiti Sahar1 , Budi Santoso1

, Budi Santoso1 , Muchtaruddin Mansyur2

, Muchtaruddin Mansyur2 , Syamikar Baridwan Syamsir3

, Syamikar Baridwan Syamsir3

-

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2024;57(3):197-211.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.24.042

Published online: May 3, 2024

- 1,712 Views

- 182 Download

1Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia

2Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia

3Faculty of Nursing Science, Universitas Muhammadiyah Jakarta, Jakarta, Indonesia

- Corresponding author: Agus Setiawan, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Building A, Health Sciences Cluster, UI Campus Depok, Depok 16424, Indonesia E-mail: a-setiawan@ui.ac.id

Copyright © 2024 The Korean Society for Preventive Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Objectives:

- Recovery from drug addiction often poses challenges for the recovering person. The coping mechanisms employed by these individuals to resist temptations and manage stress play a key role in the healing process. This study was conducted to explore the coping strategies or techniques that individuals with addiction use to handle stress and temptation while undergoing treatment.

-

Methods:

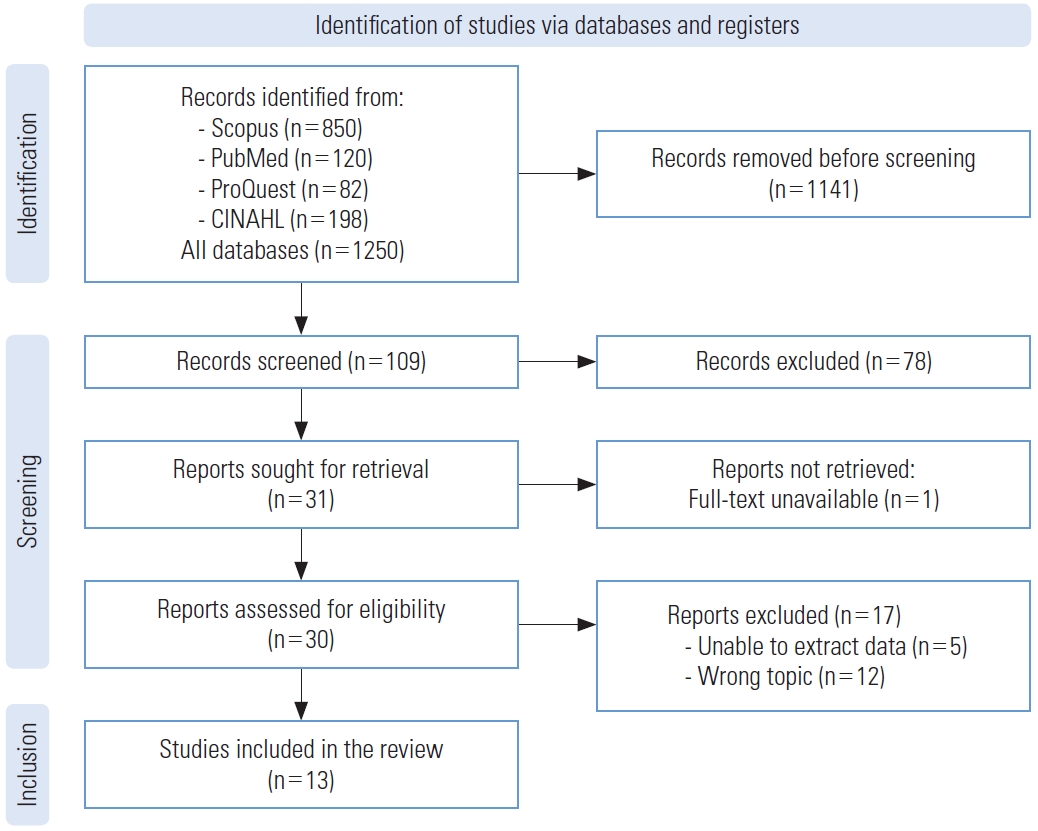

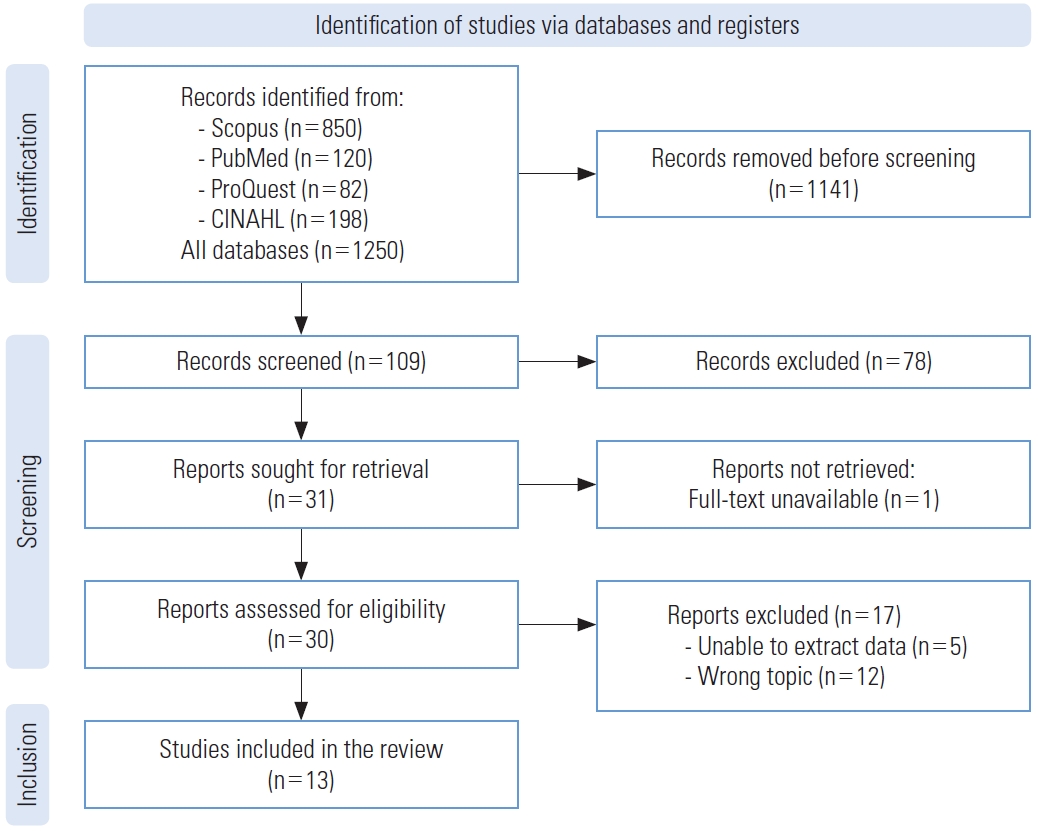

- A qualitative meta-synthesis approach was utilized to critically evaluate relevant qualitative research. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines were used for article selection, with these standards applied to 4 academic databases: Scopus, PubMed, ProQuest, and CINAHL. The present review included studies published between 2014 and 2023, selected based on pre-established inclusion criteria. The quality of the studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Studies Checklist. This review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the registration number CRD42024497789.

-

Results:

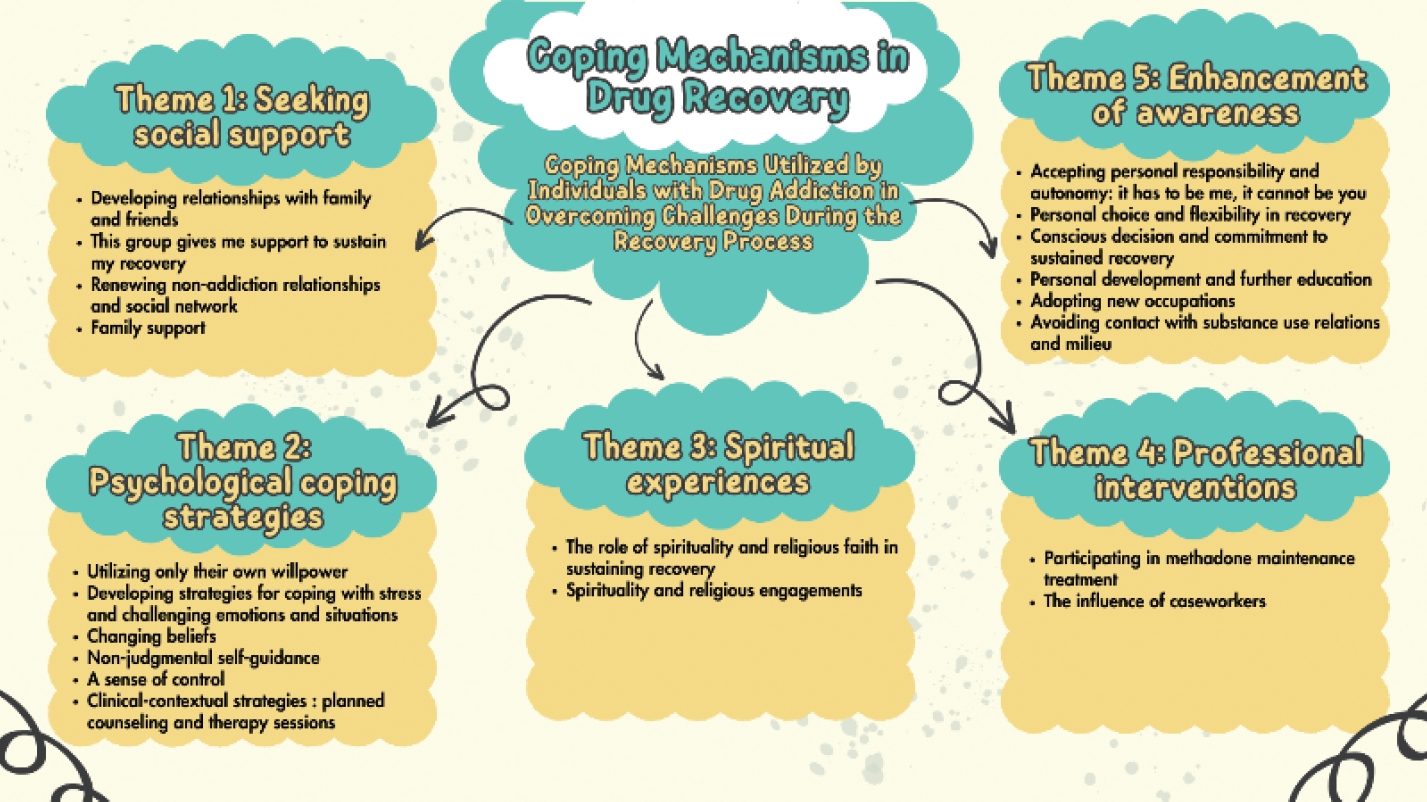

- The analysis of 13 qualifying qualitative articles revealed 5 major themes illustrating the coping mechanisms employed in the pursuit of recovery by individuals who use drugs. These themes include seeking social support, as well as psychological coping strategies, spiritual experiences, professional interventions, and the enhancement of awareness.

-

Conclusions:

- Among individuals with drug addiction, coping mechanisms are crucial for resisting stress and temptations throughout the recovery process. Healthcare professionals, as medical specialists, can establish more thorough and effective plans to support these patients on their path to recovery.

- Drug addiction is increasingly recognized as a public health concern in low-income and middle-income countries. This condition, characterized by the harmful or dangerous use of psychoactive substances such as alcohol and illegal narcotics, is a rapidly escalating global crisis that claims lives and poses serious health and social challenges [1,2]. The World Drug Report 2023 indicates that approximately 296 million people across the globe used drugs in 2021, equating to 1 in 17 individuals aged 15 years to 64 years. This figure marks a 23% increase from a decade prior [3]. Among these users, an estimated 39.5 million people have substance use disorder: a condition involving excessive and persistent drug use, which can disrupt the individual’s health, employment, and social relationships [3]. In Indonesia, individuals who used drugs numbered around 3.3 million in 2023, representing about 1.73% of the nation’s total population [4].

- If not addressed, this situation can have severe consequences for individuals’ lives. Research has shown that the unsupervised use of psychoactive drugs carries substantial health risks. Such use can lead to the development of drug use disorders, increase the risks of morbidity and mortality, and cause suffering and impaired functioning in various aspects of life. Effects include decreased social and economic stability, negatively impacted family relationships, legal issues, and reduced individual productivity [5,6]. For instance, drug use is linked to a heightened risk of overdose, the transmission of infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis, and mental health problems that often accompany addiction [6]. The uncontrolled nature of drug use and its adverse consequences must be addressed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that individuals who receive effective drug treatment can recover and return to a healthy life [7].

- Recovery from drug addiction is crucial not only for individuals grappling with addiction but also for society. Despite the challenges, evidence suggests that the majority of individuals with drug addiction eventually achieve recovery through regular treatment [8]. Recovery is characterized by a reduction or complete cessation of substance use and includes improvements in personal, functional, and social aspects of life; it is also a socially negotiated process [9,10]. The positive impact of successful recovery from drug addiction is substantial. In addition to enhancing quality of life among those once overshadowed by addiction, recovery can bolster physical and mental health, diminish the risk of overdose and drug-related diseases, and foster improved emotional and psychological well-being [11].

- Recovery also plays a crucial role in repairing social relationships. Drug addiction frequently results in conflicts and damage to relationships with family, friends, and the community [12]. As individuals recover from addiction, they experience opportunities to repair and fortify these social bonds, which can help build social support and a stronger sense of connection with those around them [13,14]. Moreover, recovery positively impacts productivity and quality of life. Individuals who overcome addiction are often better able to concentrate on work, education, and other life goals than they were before recovery [15,16].

- However, recovery from drug addiction is a challenging journey fraught with complexities. Those seeking to overcome addiction can encounter various obstacles, including physical health issues and withdrawal symptoms as well as psychological hurdles such as emotional distress, low self-esteem, and mental health disorders that may precipitate relapse [17,18]. The role of coping mechanisms in recovery is crucial, as these strategies profoundly impact the achievement of positive recovery outcomes. Effective coping mechanisms empower individuals to withstand the urge to revert to drug use, to handle stress encountered during recovery, and to build a healthy and happy life free from drug dependence [19]. Coping encompasses the thoughts and behaviors utilized to navigate stressful internal and external situations [20].

- No meta-synthesis study has thoroughly explored how individuals recovering from drug addiction manage stress or resist the temptation to relapse. Research must be conducted to fill the knowledge gap stemming from the scarcity of specialized literature on this topic. Investigation of this area can substantially enhance our scientific understanding of effective coping mechanisms in the treatment of drug addiction. Healthcare professionals stand to gain considerably from the insights this research may provide regarding intervention and rehabilitation efforts. Therefore, this study was performed to examine the coping strategies or techniques used by individuals in recovery from drug addiction to handle stress and temptation.

INTRODUCTION

- Research Design

- This systematic analysis, which employed a meta-synthesis approach, integrated findings from multiple qualitative studies to achieve a deeper and more thorough understanding of the relevant social phenomena and research topic [21]. The qualitative methodology was chosen for its distinctive capacity to explore subjective experiences and the complexities of social interactions, in this case those associated with coping strategies in drug addiction recovery. Research suggests that qualitative research is particularly useful when an exploratory approach is necessary for less-understood topics, if phenomena cannot be adequately explained by quantitative research, or when introducing new perspectives that are difficult to clarify using prevailing views [22].

- In this study, we aimed to understand the coping strategies and mechanisms employed by individuals in recovery from drug addiction to manage temptation and stress. Recognizing the considerable diversity in the nature and impact of various drugs, we delineated the scope of our research to focus specifically on addiction to opioids, stimulants, and cannabis [1]. This focus is informed by the high prevalence and distinct set of challenges associated with these substances, which include broad impacts on both physical and mental health and present meaningful obstacles in the journey to recovery [23].

- The meta-synthesis process comprised 5 systematic steps: (1) identifying the research question and formulating search components using the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type) tool (Table 1), which served as a framework in the Methods section for screening and selecting relevant studies; (2) identifying relevant articles based on established inclusion criteria; (3) critically appraising the selected articles; (4) developing themes through data extraction and text coding; and (5) interpreting and synthesizing the concepts [24].

- Identification of the Research Question

- After conducting a preliminary study that analyzed various phenomena and identified gaps in the previous research, the authors formulated their research question using the SPIDER approach (Table 1) [25]. The resulting question is as follows: “What coping mechanisms or strategies do individuals use in the process of recovering from drug addiction to deal with temptation or stress?”

- Eligibility Criteria

- The article search was guided by specific research criteria, which were based on the SPIDER search components (Table 1) in addition to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria encompassed relevant qualitative studies that focused on coping strategies in recovery from drug addiction, published within the past decade (2014-2023) and written in English. Conversely, the exclusion criteria ruled out quantitative research, studies not relevant to the topic, and research of low quality. The search strategy employed Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and utilized the academic databases Scopus, PubMed, ProQuest, and CINAHL.

- We utilized a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram to delineate the steps of data retrieval from the identified articles. This approach helps minimize bias and supports the desired transparency and systematic nature of the article selection process [26]. The PRISMA flow diagram aided in depicting the selection procedure, assisting in ensuring the accuracy and relevance of the studies included in the thematic analysis of this literature review (Figure 1). Additionally, this meta-synthesis was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the registration No. CRD420244 97789 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42024497789).

- Quality Assessment

- This study utilized the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) version 2018 [27] to evaluate relevant articles. CASP serves as a guide for researchers or authors conducting systematic reviews, aiding in the assessment of the quality and relevance of scientific research, particularly within the health field. This tool helps ensure the validity and quality of the selected articles [28]. The quality assessment and critical appraisal were independently carried out by 2 authors—JS and AS—using the 10 assessment criteria outlined in Table 2, as recommended by source [28]. These criteria helped categorize the research outcomes into either high or low validity [29]. Overall, all articles were determined to display high validity. However, the reflexivity question component was found to be unclear in 3 articles, specifically those by Bjornestad et al. [30], Nhunzvi et al. [31], and Appiah et al. [32]. These publications provided insufficient detail regarding the relationship between the researchers and participants throughout the research process. The assessment findings for the articles are detailed in Table 2.

- Analysis and Synthesis of Studies

- After completing the first 3 stages of the meta-synthesis process—formulating the research question, selecting articles, and critically appraising them—the next step involves developing main themes and interpreting the findings through analysis and synthesis [24]. During this stage, the authors analyzed the findings from each study to identify common patterns, differences, and similarities in the coping strategies employed by individuals recovering from drug addiction. The authors meticulously and repeatedly examined the selected articles to assess, understand, identify, extract, note, organize, compare, relate, map, stimulate, and verify the findings of each study.

- For data interpretation, the thematic synthesis method described by Thomas and Harden [33] was employed. Throughout this process, the authors also considered the research methodologies used, the data collection techniques employed, and the emergence of themes and key quotes that supported the research focus. Using an inductive approach, the authors categorized key elements of the articles into relevant codes and examined patterns that emerged from the data. These patterns allowed the authors to develop new conceptual themes that provided insights into the research question. The results of this analysis were integrated through a synthesis process, which facilitated a deeper understanding of the coping strategies used by individuals during their recovery from drug addiction. The reviewers then matched these descriptive themes with the textual data from the studies, enabling analytical themes to emerge. These themes were refined through discussions among 3 reviewers (AS, JS, and SBS). Discrepancies in opinion were resolved through discussion until consensus was achieved [34]. The final stage of this process involved interpreting the developed themes within the broader context of the research in the Discussion section.

- Ethics Statement

- This study used a qualitative meta-synthesis method that exclusively drew data from published articles. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required as there was no direct interaction with human subjects or animals.

METHODS

- After conducting the systematic search and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the authors identified 13 articles that were relevant to the research objectives. All identified articles were qualitative in nature. Among these studies, 4 were conducted in Norway. The remainder were carried out in various countries, with 1 each in China, the Netherlands, Malaysia, Indonesia, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Ghana, and Canada. The characteristics of the 13 synthesized studies are detailed in Table 3 [30-32,35-44].

- The synthesis process was carefully and systematically performed by all authors, each of whom had experience in conducting and publishing qualitative research. The emergence of new themes from this synthesis considered several key factors, including the depth and completeness of the data, the methodologies and data analysis techniques used, and the relevance of the findings to the research objectives. Additionally, the authors carefully examined the consistency and variations evident in the data.

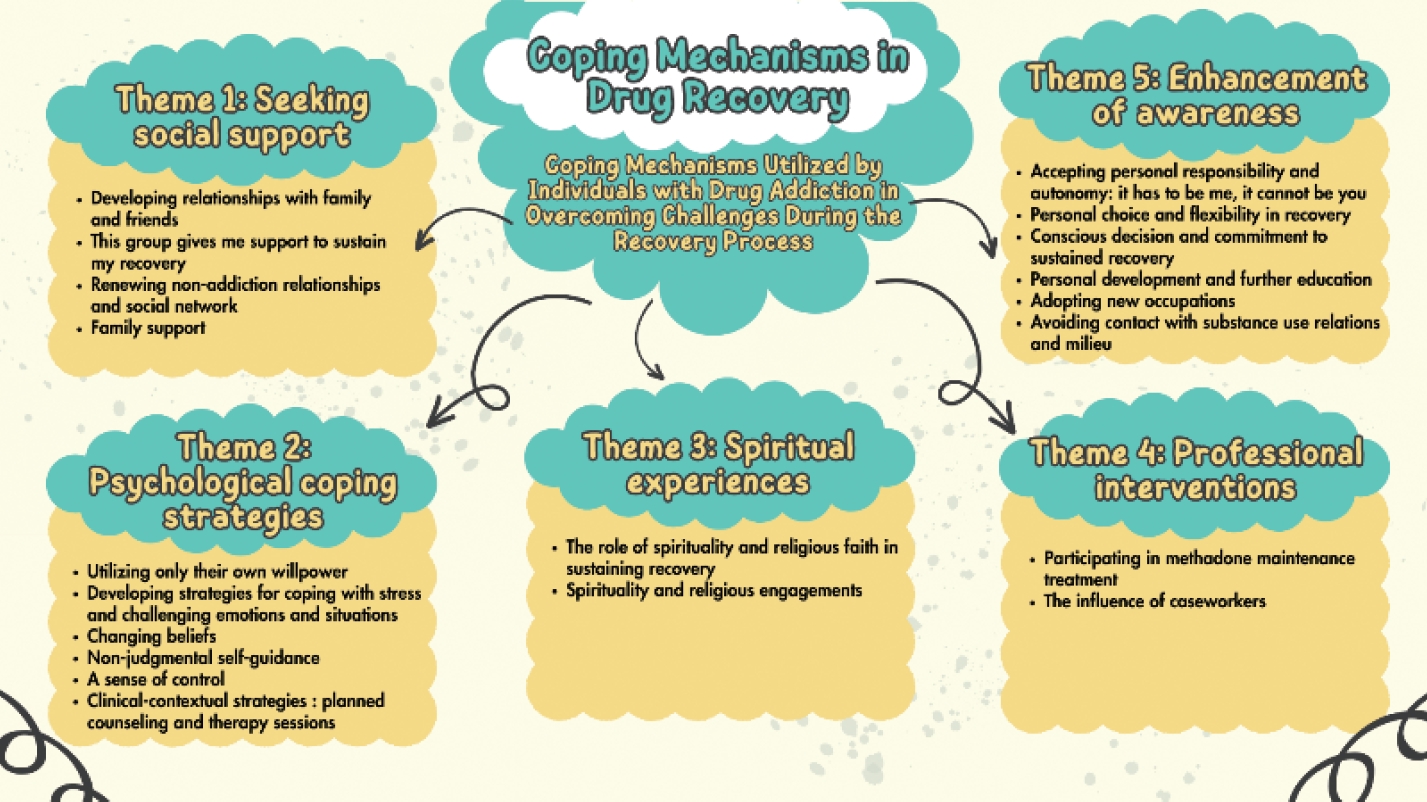

- The analysis results revealed 5 main themes characterizing the diverse coping strategies individuals employ throughout recovery from drug addiction (Table 4). These themes were: (1) seeking social support; (2) psychological coping strategies; (3) spiritual experiences; (4) professional interventions; and (5) the enhancement of awareness (Figure 2).

- Theme 1: Seeking Social Support

- Social support is crucial in the recovery from addiction. This theme emphasizes the importance of healthy relationships with family, friends, and the broader community, which create an emotional support network for those recovering from drug addiction [35,36]. Such support provides motivation, positive reinforcement, and essential resources to manage cravings and stress throughout the recovery process. Participation in support groups and the establishment of non-addictive social ties can reduce feelings of isolation, strengthen resistance to relapse, and encourage the adoption of healthier behavior patterns [37,38].

- Theme 2: Psychological Coping Strategies

- Psychological coping strategies comprise efforts that focus on the development and application of specific techniques to manage stress, negative emotions, and triggering thoughts. This process includes building self-confidence, altering beliefs and attitudes, accepting situations, making conscious choices, and engaging in self-relaxation therapy [32,35,39-41]. Individuals often employ these strategies to confront internal challenges commonly associated with addiction, such as anxiety, depression, or trauma. The development of effective coping strategies is essential for long-term recovery and can reduce the risk of relapse.

- Theme 3: Spiritual Experiences

- Spiritual experiences frequently play a key role in addiction recovery. Multiple studies have demonstrated that individuals often draw strength, hope, and motivation from spiritual experiences or religious beliefs. Prevalent coping tactics involve integrating spiritual or religious principles into daily life, engaging in religious activities, or pursuing a deeper sense of meaning and purpose [32,36]. Spirituality can assist individuals in addressing addiction by offering a fresh perspective and supporting the development of an identity not defined by addiction.

- Theme 4: Professional Interventions

- Professional interventions describe the ways in which individuals with drug addiction engage with mental health and medical services to support their recovery. These individuals may adopt coping strategies that include medication-assisted therapy, counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and other forms of assistance from healthcare professionals [39,42]. The aim of these interventions is to tackle both the biological and psychological facets of addiction, offer expert guidance and support, and help in forging more effective and sustainable strategies for recovery.

- Theme 5: Enhancement of Awareness

- The fostering of awareness is associated with a deeper recognition and comprehension of addiction and the recovery process. A key coping strategy involves individuals taking personal responsibility for their recovery, consciously deciding to steer clear of triggers, and committing to lifestyle changes [30,36,43]. Additionally, awareness enhancement encompasses education on the intricacies of addiction, the development of self-awareness, and the acknowledgment of the importance of selecting a recovery path that aligns with one’s needs and circumstances [31,36,38].

RESULTS

- The authors conducted a meta-synthesis of 13 qualitative research studies to offer a detailed description of the coping mechanisms utilized by individuals experiencing drug addiction recovery. The results of the synthesis identified various coping strategies, including: (1) seeking social support; (2) psychological coping strategies; (3) spiritual experiences; (4) professional interventions; and (5) the enhancement of awareness.

- The synthesis analysis identified “seeking social support” as the first theme. Social support theory explores the ways in which social connections and interactions provide practical, emotional, and informational support to individuals facing challenges that impact their coping strategies, overall health, and well-being [45]. This definition of social support encompasses the assistance received from social ties with family, friends, groups, and the broader society [46]. Within the scope of this study, possessing strong relationships with family and friends is considered essential, as they can offer a sense of security and comfort that is crucial during the recovery process. Not only do these relationships provide emotional support, but family members and friends can also supply motivation, enhance self-efficacy, and empathize with the individual’s recovery experience [47,48]. Primary sources of emotional, instrumental, and informational support for those in recovery from drug addiction include family, friends, therapists, support groups, and non-profit organizations [49,50]. These constitute the foundations of the support networks that are crucial for individuals with addiction.

- Stress is viewed as a key factor that can trigger cravings and increase the risk of relapse in drug addiction [51]. Research demonstrates a relationship between social support and various aspects of health and well-being; notably, a lack of social support can adversely impact psychological and physical health [52]. Furthermore, prior findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of social and emotional support tend to face lower mortality rates than those with less support [53]. Establishing connections with family, friends, or peers undergoing similar recovery journeys is regarded as a beneficial step in the context of aiding individuals with rehabilitation [54].

- The next theme in this study, “psychological coping strategies,” offers valuable insights into the methods those recovering from addiction employ to navigate challenges and resist temptations. In their efforts to overcome drug addiction, individuals may draw upon their personal strengths [39]. They develop psychological coping mechanisms to manage stress, uncomfortable emotions, and adverse situations [35]. Furthermore, the success of rehabilitation heavily depends on changes in one’s beliefs and self-perceptions [40]. Research underscores the importance of patients’ confidence in their own abilities and talents as a means to effectively prevent relapse [55]. Moreover, the subthemes of “non-judgmental self-guidance” and “a sense of control” are integral to the psychological coping strategies utilized by those with addiction. These strategies highlight the importance of perceiving control over one’s circumstances and fostering positive self-support during recovery [41]. Overall, these elements suggest that individuals working to overcome drug addiction endeavor to cultivate supportive thought patterns and avoid negative self-judgment. Moreover, some studies have incorporated structured therapies, such as self-administered progressive muscle relaxation, to aid in the process [32].

- The theme of “spiritual experiences” also characterizes coping strategies employed by individuals with drug addiction during the recovery process. This theme underscores the vital role of spirituality in the efforts to recover from drug addiction. Studies indicate that those with addiction often turn to their spiritual and religious beliefs for support to help them resist temptations and manage stress during recovery [32,36]. Additional research suggests that spirituality can represent a source of strength and peace for those endeavoring to overcome drug addiction [56].

- Furthermore, the theme “utilizing healthcare services through professional interventions” underscores the key role played by professional intervention in aiding individuals throughout the recovery process. These findings suggest that those with addiction often rely on professional interventions as an essential component of their strategy to cope with temptation and stress during recovery. Within this framework, two subthemes emerge: “participation in methadone maintenance treatment” and “the influence of social workers.” These subthemes highlight the importance of treatment programs and social workers in offering the necessary support throughout the recovery process [39,42]. Additionally, qualitative studies underscore the role of nurses in caring for patients with drug addiction and the need for high-quality services and appropriate guidance from comprehensive care providers [57].

- In addiction recovery, interprofessional collaboration is essential for providing holistic support to individuals experiencing addiction. This collaboration facilitates an integrated approach that includes the monitoring of physical health, psychosocial support, cognitive behavioral therapy, counseling, medical management, and the provision of necessary emotional support [58,59]. With a range of knowledge and perspectives, interdisciplinary teams can establish coordinated and effective care plans tailored to the needs of each individual, thereby improving recovery outcomes [60].

- The final theme that emerged from this study is “enhancement of awareness,” which underscores the importance of developing self-awareness as a key strategy for individuals navigating drug addiction recovery. This concept comprises several subthemes, including the acceptance of personal responsibility and autonomy, the exercise of personal choice and flexibility in recovery, the making of deliberate decisions and commitment to sustained recovery, self-improvement and continued education, career changes, and efforts to avoid contact with environments and individuals associated with substance abuse [30,31,36,38,43]. The findings suggest that individuals on the path to recovery from drug addiction often develop a strong capacity for self-awareness and personal responsibility. They may proactively make decisions that facilitate their recovery journey, including modifications to lifestyle, education, and employment. This reflects their commitment to long-term recovery and efforts to avoid temptations that may arise in their surroundings. Self-awareness of one’s addiction is the crucial initial step in the recovery process, as it allows individuals to acknowledge the challenges they face and seek appropriate solutions [61]. Research further indicates that self-awareness can serve as a potent motivator, spurring individuals to persist in their recovery while being aware of the risks and detrimental effects associated with drug addiction [62].

- However, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. For one, as a meta-synthesis, it is reliant upon the quality and diversity of data available in the previously published literature. Variability in the quality of initial data from the included studies, as well as differences in the research methods employed, can impact the validity of the synthesized findings. Furthermore, limitations in the number of relevant qualitative studies may constrain the range of themes identified and limit the authors’ capacity to make robust generalizations from the analyzed studies. Nevertheless, efforts were made to incorporate as many studies as possible that satisfy the inclusion criteria, aiming to provide a more thorough overview of the coping strategies employed by individuals recovering from drug addiction.

- To address these limitations, we recommend the following for further research: (1) broadening the literature search to encompass a wider array of qualitative studies, including those published in languages other than English, to capture a more diverse range of themes; (2) undertaking longitudinal studies that involve collecting data from participants over longer periods to understand changes in the use of coping strategies throughout the recovery process; and (3) exploring the impact of contextual factors, such as the social and cultural environments, on the selection and effectiveness of coping strategies among individuals recovering from drug addiction. By adopting these recommendations, future research can enhance our comprehension of coping strategies within the context of drug addiction recovery and address the limitations identified in this study.

DISCUSSION

- This study highlights various coping strategies employed by individuals recovering from drug addiction. Utilizing the meta-synthesis method, we identified 5 types of coping strategies from an analysis of 13 pertinent studies. These strategies are: seeking social support, psychological coping strategies, spiritual experiences, professional interventions, and the enhancement of awareness. These findings offer deeper insights into how individuals confront the challenges of temptation and stress throughout their recovery from drug addiction. The practical implications of this study are noteworthy, particularly with regard to improving the care and support provided to those experiencing drug addiction. By understanding the diverse coping strategies utilized by individuals with drug addiction, healthcare professionals, including community nurses, can develop more holistic and effective methods to support patients on their path to recovery.

CONCLUSION

-

Data Availability

The data examined and presented in this article originate entirely from the publicly available published literature.

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

-

Funding

This research is supported by HIBAH PUTI 2022, funded by the Directorate of Research and Community Engagement at Universitas Indonesia.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Setiawan A, Sahar J, Santoso B. Data curation: Syamsir SB, Setiawan A, Sahar J, Santoso B, Mansyur M. Formal analysis: Syamsir SB, Setiawan A, Sahar J. Funding acquisition: Setiawan A, Sahar J, Santoso B. Methodology: Syamsir SB, Setiawan A, Sahar J. Project administration: Setiawan A, Sahar J. Visualization: Setiawan A, Syamsir SB. Writing – original draft: Setiawan A, Sahar J, Santoso B, Mansyur M, Syamsir SB. Writing – review & editing: Setiawan A, Sahar J, Santoso B, Mansyur M, Syamsir SB.

Notes

Acknowledgements

| Study | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 5. Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 10. How valuable is the research? | CASP quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjornestad et al., 2019 [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Nhunzvi et al., 2019 [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Appiah et al., 2018 [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Wangensteen et al., 2022 [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Stokes et al., 2018 [36] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Shaari et al., 2023 [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Pettersen et al., 2023 [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Yang et al., 2015 [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Iswardani et al., 2022 [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Dundas et al., 2020 [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Brunelle et al., 2015 [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Rettie et al., 2020 [43] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Martinelli et al., 2023 [44] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Study | Country | Research objective | Participants | Data collection | Design of the study | Method of data analysis | Main themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjornestad et al., 2019 [30] | Norway | To investigate the subjective experiences of long-term recovery from SUD, focusing on functional and social factors | Thirty long-term recovered adult users of substance use treatment services | In-depth interviews | Phenomenological study | Semantic analysis | - Paranoia, ambivalence, and drug cravings: extreme barriers to ending use |

| - Submitting to treatment: a struggle to balance rigid treatment structures with a need for autonomy | |||||||

| - Surrendering to trust and love: building a whole person | |||||||

| - A life more ordinary: surrendering to mainstream social responsibilities | |||||||

| - Accepting personal responsibility and autonomy: it has to be me, it cannot be you | |||||||

| Nhunzvi et al., 2019 [31] | Zimbabwe | To explore the journey of recovery from substance abuse among young adult Zimbabwean men | Three young adult men | Iterative in-depth narrative interviews | Qualitative narrative inquiry | Narrative analysis | - Substance abuse as our occupation |

| - Recovery from substance abuse: an ongoing transition | |||||||

| - Recovery from substance abuse: a change of occupational identity | |||||||

| Appiah et al., 2018 [32] | Ghana | To explore relapse prevention strategies used by patients recovering from poly-substance use disorders in Ghana | Fifteen patients recovering from poly-substance use disorders | In-depth interviews using a semi-structured guide | Descriptive phenomenology | Content analysis | - Clinical-contextual strategies |

| - Spirituality and religious engagements | |||||||

| - Communal spirit and support network | |||||||

| Wangensteen et al., 2022 [35] | Norway | To investigate patients’ reflections on their experiences in inpatient treatment for SUD 4 y after exiting treatment | Eleven former patients (6 women and 5 men), aged 30-45 y with a history of severe substance use issues | In-depth interview | Qualitative study | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | - Treatment content and relationships that were considered valuable |

| - Treatment content and relationships that were considered useless or harmful | |||||||

| Stokes et al., 2018 [36] | South Africa | To deeply understand how individuals recovering from SUD experience and maintain their recovery | Fifteen participants, including 9 men and 6 women | In-depth face-to-face individual interviews | Qualitative study with narrative and phenomenological design | Tesch 8-step data analysis process | - The transitions that led to the journey of sustained recovery |

| - Psychological mindset as strategy to help sustain their recovery | |||||||

| - Social support | |||||||

| - External and environmental changes | |||||||

| - Helping others | |||||||

| Shaari et al., 2023 [37] | Malaysia | To explore the factors that motivate individuals in recovery from SUDs to remain in self-help groups | Five members of self-help groups currently recovering from SUDs | Online focus group | Qualitative study | Thematic analysis | - This group gives me support to sustain my recovery |

| - This group empowers me to give back to society | |||||||

| - This group has a leader who gives me hope | |||||||

| Pettersen et al., 2023 [38] | Norway | To explore the experiences of former patients with SUD, focusing on the benefits and challenges of a reoriented identity and way of living after recovery | Ten participants who had completed treatment for SUD | Semi-structured interviews | Qualitative study | Content analysis | - Avoiding illegal drugs |

| - Avoiding contact with substance use relations and milieu | |||||||

| - Renewing non-addiction relationships and social network | |||||||

| - Establishing an occupation | |||||||

| - Discovering the value of the great, little things in everyday life | |||||||

| Yang et al., 2015 [39] | China | To understand the experiences of individuals who use drugs during abstinent periods and explore the factors contributing to drug use relapse | Eighteen participants, with an average age of 33 y (range, 18-41); the average duration of drug use was 12 y (range, 3-19) | Face-to-face, in-depth interview | Qualitative study | Thematic analysis | - Ways of overcoming withdrawal and the driving force for abstinence |

| - Experiences during periods of abstinence | |||||||

| - “Why I relapse” | |||||||

| Iswardani et al., 2022 [40] | Indonesia | To explore the process of meaning-making in individuals with drug addiction before, during, and after drug use and recovery | Five men in recovery from addiction, aged 26-49 y, who were abstinent for 4-17 y | In-depth interviews | Qualitative case study | Deductive thematic analysis | - Feeling that things make sense |

| - Accepting the situation | |||||||

| - Reattribution/having a causal understanding | |||||||

| - Existence of the perception of growth or a positive change in life | |||||||

| - Changing identity | |||||||

| - Reassessing the meaning of the stressor | |||||||

| - Changing global belief | |||||||

| - Changing global purpose | |||||||

| - Restoring/changing meaning in life | |||||||

| Dundas et al., 2020 [41] | Norway | To explore how participants used a mindfulness-based program to reduce their long-term use of habit-forming prescription drugs and their post-intervention strategies for controlling medication intake | Eighteen participants | Semi-structured qualitative interviews | Qualitative study | Inductive semantic thematic analysis | - Increased present-moment sensory awareness: noticing all the things one usually takes for granted |

| - Observing without controlling: managing to “uncouple” oneself from distressing thoughts | |||||||

| - Self-acceptance: no longer hitting oneself over the head | |||||||

| - Making conscious choices: reflecting before taking a pill, and sometimes not taking it | |||||||

| - Non-judgmental self-guidance: what else might you do? | |||||||

| - A sense of control: there is something I can do | |||||||

| Brunelle et al., 2015 [42] | Canada | To understand the experiences of individuals with drug dependency and the sources that motivate them to change | A total of 127 adults with drug dependency | Focused semi-structured interviews | Qualitative study | Thematic content analysis | - Quality of life |

| - Accumulation of services | |||||||

| - The role of caseworkers | |||||||

| - Collaboration between professionals | |||||||

| Rettie et al., 2020 [43] | UK | To explore the personal experiences of individuals recovering from drug or alcohol dependency who participate in social-based recovery groups | Ten individuals recovering from drug dependency | Semi-structured interviews | Qualitative study | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | - The group’s role in recovery |

| - Personal choice and flexibility in recovery | |||||||

| - The group as an inclusive family unit | |||||||

| - Active involvement in the recovery group | |||||||

| Martinelli et al., 2023 [44] | The Netherlands | To understand the process of drug addiction recovery through direct experiences of individuals at various stages of recovery | Thirty participants, both men and women, in stages of drug addiction recovery | In-depth qualitative interviews | Qualitative study | Thematic analysis | - Recovery is a broad process of change because addiction is interwoven with everything |

| - Recovery is reconsidering identity, seeing things in a new light | |||||||

| - Recovery is a staged long-term process | |||||||

| - Universal life processes are part of recovery |

| Developed themes | Findings (themes, subthemes, or categories) from the original article | Participant quotation (from the original article) | Relevant study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Seeking of social support | Developing relationships with family and friends | “They made me aware of how important I am to my children… When you have children, you have an obligation to stay sober. I stay sober for my partner and my children.” | Wangensteen et al., 2022 [35] |

| This group gives me support to sustain my recovery | “I am stronger today because I have support from him [group leader]. He teaches me how to make the right decisions to make sure I can keep my recovery in check.” | Shaari et al., 2023 [37] | |

| Renewing non-addiction relationships and social network | “But having a healthy network is perhaps the most essential thing to stay clean.” | Pettersen et al., 2023 [38] | |

| Family support | “So I had amazing family support, my dad as well. For them, like just seeing what the programme did for me, it was such a miracle… So my family is extremely supportive.” | Stokes et al., 2018 [36] | |

| Theme 2: Psychological coping strategies | Utilizing only their own willpower | “You know, I tried to quit drugs for about two months using just my willpower in 2002, when I had just gotten addicted [to heroin]. During the first month [of abstinence], I didn’t eat anything at all, I would vomit all the food if I did.” | Yang et al., 2015 [39] |

| Developing strategies for coping with stress and challenging emotions and situations | “They helped me with the anxiety and depression that I struggled with during the first 6 months of treatment. Suddenly, I started to cry, and I couldn’t stop. They taught me some methods that I still use when I get anxious at work.” | Wangensteen et al., 2022 [35] | |

| Changing beliefs | “In the past, drugs saved me. Now that I have been infected with HIV, to survive, I must avoid taking drugs.” | Iswardani et al., 2022 [40] | |

| Non-judgmental self-guidance | “Now I know that if I need to enter a setting that I used to need medication to enter, I can instead talk to myself and say, ‘You know, it’s actually all right that you might feel sad when in that situation, because it’s human, it’s totally okay, that [feeling].’ So that is, you know, a totally new way of thinking.” | Dundas et al., 2020 [41] | |

| A sense of control | “I believe it’s possible to practice, so that you become calmer in your body, so that you have a greater control. I’ve become much more aware of being able to calm myself.” | Dundas et al., 2020 [41] | |

| Clinical-contextual strategies: planned counseling and therapy sessions | “When I experience the feeling at the work place… and I resist… sometimes I become anxious and restless. I take a short break to do some PMR [progressive muscle relaxation] exercises I learnt from counselling. Now, I’m also able to turn down offers from my friends… gently. I don’t even go close to them anymore.” | Appiah et al., 2018 [32] | |

| Theme 3: Spiritual experiences | The role of spirituality and religious faith in sustaining recovery | “In my recovery, it’s like God played a role, of giving me the strength to be sober, understand? I mean, God is planning everything. God is doing everything. He is helping me figure things out, you know, do this and that.” | Stokes et al., 2018 [36] |

| Spirituality and religious engagements | “So my auntie took me to a prayer camp where we spent two weeks fasting and praying. It was difficult though… I had to fast and pray all the time. After a series of deliverances and prophetic utterances, the prophet told me I was free… and that was it.” | Appiah et al., 2018 [32] | |

| Theme 4: Professional interventions | Participating in methadone maintenance treatment | “…I went to a clinic, requested some intravenous drips and some tablets, and then stayed at home and lay in bed all day long… in this way, I quit heroin without suffering much. People just never believe!” | Yang et al., 2015 [39] |

| The influence of caseworkers | “Well, he [the caseworker involved in the referral] was always humane, he was understanding, and he suggested this [the treatment] to me, by sort of suggesting a decrease in my use, but not total abstinence.” | Brunelle et al., 2015 [42] | |

| Theme 5: Enhancement of awareness | Accepting personal responsibility and autonomy: it has to be me, it cannot be you | “I dunno (laughs). I don’t think about it much anymore, I just kind of get up and start the day. I don’t have many fixed routines. I am very down to earth, I just get up and drink coffee, and then I’m off really.” | Bjornestad et al., 2019 [30] |

| Personal choice and flexibility in recovery | “Everybody’s journey is different and you have to find what’s right for you.” | Rettie et al., 2020 [43] | |

| Conscious decision and commitment to sustained recovery | “…but it is a decision [referring to sustained recovery] you need to have to make at the end of the day, to decide you are never going to have [another drug again]”. | Stokes et al., 2018 [36] | |

| Personal development and further education | “So to rectify that I went to Mr Google and I started upping my professional skill, my knowledge about my work… I also start using Dr Google and learn about dependency because to help yourself you must know what you are challenging.” | Stokes et al., 2018 [36] | |

| Adopting new occupations | “If I am to sustain my journey of recovery, I need to make many changes. To construct a new life in which recovery is possible, it is necessary for me to change choices, goals, roles, and expectations. Farming is the new thing now... and I am a changed-responsible father.” | Nhunzvi et al., 2019 [31] | |

| Avoiding contact with substance use relations and milieu | “You cannot stay in the addictive subculture when you want to live in the ordinary society as sober. It is a matter of attitude, language, and ways of doing things.” | Pettersen et al., 2023 [38] |

- 1. World Health Organization. Substance abuse [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/substance-abuse#:~:text=Substance%20abuse%20refers%20to%20the,consequences%20experienced%20by%20its%20members

- 2. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global overview of drug demand and supply: latest trends, cross-cutting issues; 2018 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/prelaunch/WDR18_Booklet_2_GLOBAL.pdf

- 3. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The world drug report 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/res/WDR-2023/WDR23_Exsum_fin_DP.pdf

- 4. National Narcotics Board. Indonesian drugs report 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://cilacapkab.bnn.go.id/indonesia-drugs-report-2023/ (Indonesian)

- 5. World Health Organization. Drugs (psychoactive) [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/drugs-psychoactive#tab=tab_1

- 6. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drugs, brains, and behavior: the science of addiction [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/addiction-health#:~:text=People%20with%20addiction%20often%20have,drug%20use%20throughout%20the%20body

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recovery is possible for everyone: understanding treatment of substance use disorders; 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/featured-topics/recovery-SUD.html

- 8. Kelly JF, Bergman B, Hoeppner BB, Vilsaint C, White WL. Prevalence and pathways of recovery from drug and alcohol problems in the United States population: implications for practice, research, and policy. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;181: 162-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.028ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Helm P. Sobriety versus abstinence. How 12-stepper negotiate long-term recovery across groups. Addict Res Theory 2019;27(1):29-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1530348Article

- 10. Kelly JF, Hoeppner B. A biaxial formulation of the recovery construct. Addict Res Theory 2015;23(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2014.930132Article

- 11. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med 2014;370(22):2063-2066. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1402780ArticlePubMed

- 12. Lander L, Howsare J, Byrne M. The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: from theory to practice. Soc Work Public Health 2013;28(3-4):194-205. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2013.759005ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Daley DC. Family and social aspects of substance use disorders and treatment. J Food Drug Anal 2013;21(4):S73-S76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2013.09.038ArticlePubMed

- 14. McGaffin BJ, Deane FP, Kelly PJ, Blackman RJ. Social support and mental health during recovery from drug and alcohol problems. Addict Res Theory 2018;26(5):386-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1421178Article

- 15. Manning V, Garfield JB, Lam T, Allsop S, Berends L, Best D, et al. Improved quality of life following addiction treatment is associated with reductions in substance use. J Clin Med 2019;8(9):1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8091407ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Pasareanu AR, Opsal A, Vederhus JK, Kristensen Ø, Clausen T. Quality of life improved following in-patient substance use disorder treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13: 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0231-7ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Seyedfatemi N, Peyrovi H, Jalali A. Relapse experience in Iranian opiate users: a qualitative study. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2014;2(2):85-93PubMedPMC

- 18. Lee N, Boeri M. Managing stigma: women drug users and recovery services. Fusio 2017;1(2):65-94PubMedPMC

- 19. Abd Halim MH, Sabri F. Relationship between defense mechanisms and coping styles among relapsing addicts. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2013;84: 1829-1837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.043Article

- 20. Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol 2004;55: 745-774. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456ArticlePubMed

- 21. Thorne S. Qualitative meta-synthesis. Nurse Author Ed 2022;32(1):15-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/nae2.12036Article

- 22. Pyo J, Lee W, Choi EY, Jang SG, Ock M. Qualitative research in healthcare: necessity and characteristics. J Prev Med Public Health 2023;56(1):12-20. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.22.451ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Understanding drug use and addiction drug facts; 2018 [cited 2023 Mar 12]. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/understanding-drug-use-addiction

- 24. Williams TL, Shaw RL. Synthesizing qualitative research: metasynthesis in sport and exercise. In: Brett Smith B, Andrew C. Sparkes AC, editors. Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise. London: Routledge; 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762012

- 25. Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 2012;22(10):1435-1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938ArticlePubMed

- 26. Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, McGuinness LA. PRISMA 2020: an R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev 2022;18(2):e1230. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230ArticlePubMedPMC

- 27. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Critical appraisal checklists [cited 2023 Mar 2]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casptools-checklists/

- 28. Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Methods Med Health Sci 2020;1(1):31-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559Article

- 29. O’Connell MA, Khashan AS, Leahy-Warren P. Women’s experiences of interventions for fear of childbirth in the perinatal period: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research evidence. Women Birth 2021;34(3):e309-e321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.05.008ArticlePubMed

- 30. Bjornestad J, Svendsen TS, Slyngstad TE, Erga AH, McKay JR, Nesvåg S, et al. “A life more ordinary” processes of 5-year recovery from substance abuse. Experiences of 30 recovered service users. Front Psychiatry 2019;10: 689. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00689ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Nhunzvi C, Galvaan R, Peters L. Recovery from substance abuse among Zimbabwean men: an occupational transition. OTJR (Thorofare N J) 2019;39(1):14-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449217718503ArticlePubMed

- 32. Appiah R, Boakye KE, Ndaa P, Aziato L. “Tougher than ever”: an exploration of relapse prevention strategies among patients recovering from poly-substance use disorders in Ghana. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 2018;25(6):467-474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2017.1337080Article

- 33. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8: 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Im D, Pyo J, Lee H, Jung H, Ock M. Qualitative research in healthcare: data analysis. J Prev Med Public Health 2023;56(2):100-110. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.22.471ArticlePubMedPMC

- 35. Wangensteen T, Hystad J. Trust and collaboration between patients and staff in SUD treatment: a qualitative study of patients’ reflections on inpatient SUD treatment four years after discharge. Nordisk Alkohol Nark 2022;39(4):418-436. https://doi.org/10.1177/14550725221082366ArticlePubMedPMC

- 36. Stokes M, Schultz P, Alpaslan A. Narrating the journey of sustained recovery from substance use disorder. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2018;13(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-018-0167-0ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37. Shaari AA, Waller B. Self-help group experiences among members recovering from substance use disorder in Kuantan, Malaysia. Soc Work Groups 2023;46(1):51-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2022.2057393ArticlePubMed

- 38. Pettersen G, Bjerke T, Hoxmark EM, Eikeng Sterri NH, Rosenvinge JH. From existing to living: exploring the meaning of recovery and a sober life after a long duration of a substance use disorder. Nordisk Alkohol Nark 2023;40(6):577-589. https://doi.org/10.1177/14550725231170454ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Yang M, Mamy J, Gao P, Xiao S. From abstinence to relapse: a preliminary qualitative study of drug users in a compulsory drug rehabilitation center in Changsha, China. PLoS One 2015;10(6):e0130711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130711ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Iswardani T, Dewi ZL, Mansoer WW, Irwanto I. Meaning-making among drug addicts during drug addiction recovery from the perspective of the meaning-making model. Psych 2022;4(3):589-604. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4030045Article

- 41. Dundas I, Ravnanger K, Binder PE, Stige SH. A qualitative study of use of mindfulness to reduce long-term use of habit-forming prescription drugs. Front Psychiatry 2020;11: 493349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.493349ArticlePubMedPMC

- 42. Brunelle N, Bertrand K, Landry M, Flores-Aranda J, Patenaude C, Brochu S. Recovery from substance use: drug-dependent people’s experiences with sources that motivate them to change. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 2015;22(3):301-307. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2015.1021665Article

- 43. Rettie HC, Hogan L, Cox M. Personal experiences of individuals who are recovering from a drug or alcohol dependency and are involved in social-based recovery groups. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 2020;27(2):95-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2019.1597337Article

- 44. Martinelli TF, Roeg DP, Bellaert L, Van de Mheen D, Nagelhout GE. Understanding the process of drug addiction recovery through first-hand experiences: a qualitative study in the Netherlands using lifeline interviews. Qual Health Res 2023;33(10):857-870. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323231174161ArticlePubMedPMC

- 45. Zhou ES. Social support. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2789

- 46. Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D, Southwick S. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4(5):35-40

- 47. Stevens E, Jason LA, Ram D, Light J. Investigating social support and network relationships in substance use disorder recovery. Subst Abus 2015;36(4):396-399. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.965870ArticlePubMed

- 48. Korcha RA, Polcin DL, Bond JC. Interaction of motivation and social support on abstinence among recovery home residents. J Drug Issues 2016;46(3):164-177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042616629514ArticlePubMedPMC

- 49. Turuba R, Toddington C, Tymoschuk M, Amarasekera A, Howard AM, Brockmann V, et al. “A peer support worker can really be there supporting the youth throughout the whole process”: a qualitative study exploring the role of peer support in providing substance use services to youth. Harm Reduct J 2023;20(1):118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00853-3ArticlePubMedPMC

- 50. Scott E. The different types of social support; 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/types-of-social-support-3144960

- 51. Ruisoto P, Contador I. The role of stress in drug addiction. An integrative review. Physiol Behav 2019;202: 62-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.01.022ArticlePubMed

- 52. American Psychological Association. Manage stress: strengthen your support network; 2022 [cited 2023 Mar 2]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/manage-social-support

- 53. Grav S, Hellzèn O, Romild U, Stordal E. Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 2012;21(1-2):111-120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03868.xArticlePubMed

- 54. Lookatch SJ, Wimberly AS, McKay JR. Effects of social support and 12-step involvement on recovery among people in continuing care for cocaine dependence. Subst Use Misuse 2019;54(13):2144-2155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1638406ArticlePubMedPMC

- 55. Nikmanesh Z, Baluchi MH, Pirasteh Motlagh AA. The role of self-efficacy beliefs and social support on prediction of addiction relapse. Int J High Risk Behav Addict 2017;6(1):e21209. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.21209Article

- 56. Grim BJ, Grim ME. Belief, behavior, and belonging: how faith is indispensable in preventing and recovering from substance abuse. J Relig Health 2019;58(5):1713-1750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00876-wArticlePubMedPMC

- 57. Susanti H, Wardani IY, Fitriani N, Kurniawan K. Exploration the needs of nursing care of drugs addiction service institutions in Indonesia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2022;10(G):45-51. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2022.7778Article

- 58. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. TIP 42: substance use disorder treatment for people with cooccurring disorders; 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/tip-42-substance-usetreatment-persons-co-occurring-disorders/pep20-02-01-004

- 59. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment: a research-based guide (third edition); 2018 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/podat-3rdEd-508.pdf

- 60. Domingues LP, Dos Santos EL, Locatelli DP, Bedendo A, Noto AR. Interprofessional training on substance misuse and addiction: a longitudinal assessment of a Brazilian experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20(2):1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021478ArticlePubMedPMC

- 61. Adams M. The importance of self awareness in addiction recovery; 2017 [cited 2024 Mar 14]. Available from: https://whitesandstreatment.com/2017/11/10/self-awareness-in-addictionrecovery/

- 62. Pickard H. Addiction and the self. Noûs 2021;55(4):737-761. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12328Article

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KSPM

KSPM

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite