Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Prev Med Public Health > Volume 44(4); 2011 > Article

-

Special Article

How to Improve Influenza Vaccination Rates in the U.S. - Byung-Kwang Yoo

-

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2011;44(4):141-148.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.2011.44.4.141

Published online: July 29, 2010

Division of Health Policy and Outcomes Research, Department of Community and Preventive Medicine, University of Rochester, School of Medicine and Dentistry, NewYork, USA.

- Byung-Kwang Yoo, MD, MS, PhD. 265 Crittenden Blvd., CU 420644, Room 3178 , Rochester, New York 14620. Tel : 585-275-3276, Fax: 585-461-4532, Byung-Kwang_Yoo@urmc.rochester.edu

• Received: June 9, 2011 • Accepted: June 22, 2011

Copyright © 2011 The Korean Society for Preventive Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

- Annual epidemics of seasonal influenza occur during autumn and winter in temperate regions and have imposed substantial public health and economic burdens. At the global level, these epidemics cause about 3-5 million severe cases of illness and about 0.25-0.5 million deaths each year. Although annual vaccination is the most effective way to prevent the disease and its severe outcomes, influenza vaccination coverage rates have been at suboptimal levels in many countries. For instance, the coverage rates among the elderly in 20 developed nations in 2008 ranged from 21% to 78% (median 65%). In the U.S., influenza vaccination levels among elderly population appeared to reach a "plateau" of about 70% after the late 1990s, and levels among child populations have remained at less than 50%. In addition, disparities in the coverage rates across subpopulations within a country present another important public health issue. New approaches are needed for countries striving both to improve their overall coverage rates and to eliminate disparities.

- This review article aims to describe a broad conceptual framework of vaccination, and to illustrate four potential determinants of influenza vaccination based on empirical analyses of U.S. nationally representative populations. These determinants include the ongoing influenza epidemic level, mass media reporting on influenza-related topics, reimbursement rate for providers to administer influenza vaccination, and vaccine supply. It additionally proposes specific policy implications, derived from these empirical analyses, to improve the influenza vaccination coverage rate and associated disparities in the U.S., which could be generalizable to other countries.

- Annual epidemics of seasonal influenza occur during autumn and winter in temperate regions and have imposed substantial public health and economic burdens [1,2]. At the global level, these epidemics cause about 3-5 million severe cases of illness and about 0.25-0.5 million deaths each year [1]. Most influenza-associated deaths in industrialized countries occur among people aged 65 or older [1]. In the U.S. alone, influenza epidemics were estimated to be associated with annual averages of 36 000 deaths and 226 000 hospitalizations [3,4]. There is limited literature on the disease burden of influenza epidemics in developing countries [1].

- Because annual vaccination is the most effective way to prevent the disease or severe outcomes from the illness [1], World Health Organization (WHO) recommends it for nursing-home residents, elderly individuals, people with certain chronic medical conditions, and other groups including pregnant women, health care workers, those with essential functions in society, and children aged from six months to two years [1]. In addition to these target populations recommended by WHO, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) expanded its influenza vaccination recommendation to include all adults aged 50 or older in 2000 [2], all children aged 6 months-18 years in 2008 [5], and all ages in 2010 [2].

- Influenza vaccination coverage rates have been at suboptimal levels in many countries. For instance, the coverage rates among the elderly in 20 developed nations in 2008 ranged from 21% to 78% (median 65%) [6]. The coverage rates among the U.S. elderly have been relatively high, partly because Medicare coverage began as early as 1993. Namely, every Medicare enrollee aged 65 or older can be vaccinated against influenza with no out-of-pocket expenditure. However, influenza vaccination levels among this population appeared to reach a "plateau" of about 70% after the late 1990s [7]. Furthermore, the coverage rates for U.S. child populations have remained at less than 50% [2].

- In addition to such suboptimal coverage levels, disparities in the coverage rates across subpopulations within a country present another important public health issue. The European and American literature documents the presence of such disparities across subpopulations defined by socio-economic factors such as income and education levels [8]. Also, racial/ethnic disparities in the influenza vaccination rate have been consistently reported among the U.S. elderly [9,10] with Hispanic and African-American populations having lower influenza vaccination rates than white populations.

- Considering the low coverage rates as well as the presence of disparities in those rates, new approaches will likely be needed to achieve the U.S. Healthy People 2020 goals [11]: (a) 80%-90% vaccination coverage among the target populations and (b) eliminating disparities in influenza vaccination rates. Such new approaches would also be useful for other countries striving both to improve their overall coverage rates and to eliminate disparities.

- This review article aims to describe potential new approaches, mainly based on recently published empirical studies conducted by the author and colleagues. Specifically, this article first introduces a broad conceptual framework of vaccination, and the notion of avoidance response, a phenomenon in which patients seek vaccination in response to an ongoing influenza epidemic. It also illustrates four potential determinants of influenza vaccination based on the empirical analyses analyzing the U.S. nationally representative populations. These determinants include the ongoing influenza epidemic level, mass media reporting on influenza-related topics, the reimbursement rate for providers to administer influenza vaccination, and vaccine supply. It additionally proposes specific policy implications, derived from these empirical analyses, to improve the influenza vaccination coverage rate and associated disparities in the U.S., which could be generalizable to other countries.

INTRODUCTION

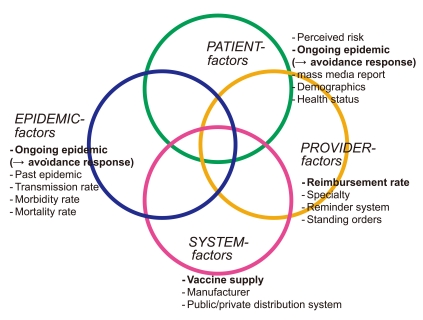

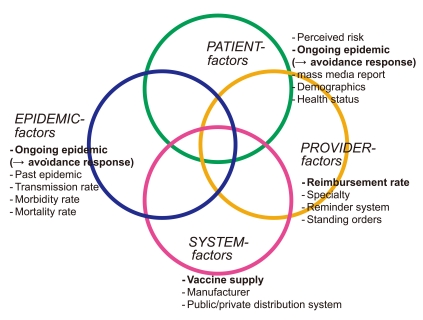

- Because a large number of factors involve vaccination, a conceptual framework is useful to categorize these factors. The conceptual framework of the studies by the author and colleagues modified frameworks offered by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services: Focus on Vaccine-Preventable Disease, and others [12,13]. The four focal domains of vaccination involve patients, healthcare providers, system and epidemic factors (Figure 1). The final domain of epidemic factors was added by the author. Epidemic factors include, ongoing and past epidemics, measured by the rates of transmission, morbidity, and mortality when infected by influenza. Perceived risk of influenza infection, among patient factors, will be affected by the information about ongoing influenza epidemic and the mass media reports on influenza infection. Examples of provider factors and system factors are reimbursement rate and vaccine supply, respectively.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

- I. Epidemic Factor: Ongoing Epidemic Leading to "Avoidance Response"

- Influenza vaccine demand, particularly late-season demand, is difficult to predict for two reasons. First, influenza vaccine manufacturers take vaccine orders as early as January of the prior season because the vaccine production process takes eight or nine months. Secondly, demand may rise when an influenza epidemic is perceived to be severe or to start early, while demand may decline when influenza epidemic activity is perceived to be mild. Because influenza activity peaks after January in most seasons, epidemic activity usually influences late-season demand [18].

- Information on "avoidance response" could improve efficiency in the distribution of influenza vaccine, particularly after the onset of an epidemic. This is because if "short-term" avoidance response exists, weekly influenza epidemic change is positively associated with overall annual influenza vaccine receipt as well as daily vaccine receipt. Empirical evidence of this association might also help predict short-term, late-season vaccine demand, enabling better seasonal influenza vaccine distribution and redistribution, thus improving the overall vaccine coverage rate. Moreover, estimation of short-term avoidance response (responsiveness) to epidemic activity might be useful in pandemic influenza planning because of the possible insufficient vaccine supply compared to the demand for pandemic vaccine [19].

- To the best of our knowledge, previous studies have quantitatively measured only long-term avoidance-response with a one-year lag, e.g., past season's epidemic level, not ongoing epidemic level. Namely, these past studies reported that a past season's higher epidemic level was associated with the subsequent season's higher vaccine coverage rates [20-22].

- The study by the author and colleagues analyzed five influenza seasons since 2000 [14]. These five seasons varied in terms of the timing and severity of the epidemics and the vaccine supply shortage/delay. This study conducted cross-sectional survival analyses from the 2000-2001 to 2004-2005 influenza seasons among the U.S. nationally representative community-dwelling elderly enrolled in the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) (weighted N=7.7 - 9.7 million per season), shown in Table 1 (row 1). The dependent variable was daily vaccine receipt, measured from September 1st in each year. Independent variables included the biweekly epidemic changes, the vaccine supply at nine census-region levels, and fifteen individual factors.

- As hypothesized, biweekly epidemic change was positively associated with overall annual vaccination (e.g., 2.7% increase in 2003-2004 season) as well as earlier vaccination timing (p<0.01), which was robust in all five seasons. The magnitude of this association was also robust in all five seasons [14]. Namely, unvaccinated individuals were 5-29% more likely to receive vaccination subsequent to a 100% biweekly epidemic increase.

- Therefore, this study concluded that the measurement of short-term avoidance response (i.e., epidemic-responsiveness in demand for influenza vaccination) may improve (a) seasonal influenza vaccine distribution and the annual seasonal influenza vaccination rate and (b) might assist pandemic influenza preparedness planning [14].

- II. Patient Factor: Mass Media Coverage on Influenza-Related Topic

- Although the previous section described ongoing epidemic level as a potential strong determinant of influenza vaccination, the peak of vaccine receipts (and vaccine campaigns) was usually prior to the end of November, well before the onset of seasonal influenza epidemic [14,18]. Additionally, some individuals tend to lose an incentive for the influenza vaccine receipt after a certain time in a season. For instance, a large number of vaccines delivered to clinics after November were unused during the 2000-2001 season with a serious vaccine supply shortage [23], although an influenza epidemic cousld start in January and end in April as observed in 2002 [24]. Therefore, to improve vaccine coverage rates during a typical influenza vaccine campaign period, another potential determinant (mass media reporting) is discussed in this section.

- The literature suggests that mass media considerably affects a person's knowledge of health and her/his use of health services [25,26]. For example, a celebrity campaign on colon cancer screening on the U.S. NBC's Today's Show was reported to increase the colonoscopy rate by 38% during the nine months following the airing of the show [27]. Although influenza was ranked 4th among all health news stories followed by the American public during 1996-2002 [26], only a few studies have measured the effect of mass media on influenza vaccination [16,28-31].

- The study by the author and colleagues [16] aimed to fill the gap in the past studies in four areas. First, these past studies analyzed at best a state-level population [28-31], not a nationally representative population. Second, these studies lacked a quantitative measure of media exposure, except one by Ma et al. [31]. Third, none of these studies controlled for other potential confounders, e.g., vaccine supply shortage. Finally, none of them explicitly measured the mass media effect on the vaccination timing (closer in time to media exposure) as well as annual vaccination rate.

- The purpose of the study by the author and colleagues [16] was to examine the association between mass media coverage on flu-related topics and influenza vaccination - concerning both vaccination timing and annual vaccination rates - among a nationally representative Medicare elderly population. Focusing on short time frames enabled this study to distinguish, at the individual level, between media exposure prior to vaccination and unrelated media exposure after vaccination. It also allowed this study to adjust for vaccine shortages at short intervals.

- The study by the author and colleagues focused on the U.S. nationally representative community-dwelling elderly, enrolled in 1999, 2000 and 2001 MCBS [16]. This study performed cross-sectional survival analyses during each of three influenza vaccination seasons between September 1999 and December 2001, as in Table 1 (row 2). The dependant variable was daily vaccine receipt measured from September 1 in each season. Daily media coverage was measured by counting the number of television program transcripts (in 4 major networks - ABC, CBS, FOX and NBC) and national newspaper/wire service articles (USA Today and Associated Press), including keywords of influenza/flu and vaccine shortage/delay. All models' covariates included three types of media, CDC press release, vaccine supply, three regional factors, and seventeen individual factors.

- Influenza-related reports in all three mass media sources had a positive association with earlier vaccination timing as well as annual vaccination rate [16]. Among these three mass media sources, television networks' reports had the most consistent positive effects in all models, e.g., changing the mean vaccination timing earlier by 1.8-4.1 days (p<0.001) or raising the annual vaccination rate by 2.3-7.9% (p<0.001). Particularly, these associations tended to be stronger when reported in a headline rather than in text only and if including additional keywords, e.g., vaccine shortage/delay.

- This study's empirical results might help justify and strengthen various forms of vaccination campaigns by CDC or other public institutions [16]. Specific policy implications for campaigns using mass media (newspapers or television) are exemplified by: (i) using a headline, as well as text, which includes specific key words like shortage/delay in addition to influenza alone; (ii) performing repeated media campaign use rather than one-time use, because of the suggested short-term media effect and the cumulative effects during a period; and (iii) securing adequate vaccine supply prior to a media campaign release on supply delay/shortage due to individuals' quick response to such release [16].

- III. Provider Factor: Reimbursement Rate for Physician Providers

- Physician recommendations have been reported to be among the strongest predictors of influenza vaccine receipt among the U.S. population [2]. Therefore, exploring an appropriate physician reimbursement policy is important to increase the vaccination coverage rates.

- It should be noted that a U.S. reimbursement policy for vaccination consists of two components, i.e., reimbursement for vaccine purchase and vaccine administration. The former component's financial risk for providers was reduced substantially after the launch of the U.S. federal program Vaccine for Children (VFC) which delivers free vaccines for eligible providers [32]. However, the latter component's financial risk for providers still remains if the actual provider costs of administering vaccinations are higher than the reimbursement rate.

- Three phenomena on influenza vaccination motivated the study by the author and colleagues [15]. First, compared to provider costs for administering child influenza vaccination ($20 per dose at the national-level in 2006 U.S. dollar) [33], inadequate reimbursement rates were reported by recent studies [33-35]. For instance, the provider cost of $20 was much higher than the average state Medicaid reimbursement rate of $8 (ranging from $2 to $18) in 2005 [15]. Second, wide disparities have been noted in influenza vaccination rates between poor and higher-income children and across states [36-38]. For instance, the influenza vaccine coverage rates among the children aged 6-23 months at the state level ranged from 1.6% (in Mississippi State) to 40.6% (in Rhode Island State) in 2005 [37]. Third, although some literature exists to suggest that higher reimbursement may improve vaccination levels [39,40], most of the evidence is either indirect or pertains to adult vaccinations.

- Based on these phenomena, two hypotheses were proposed: (1) In the individual-level multivariate analysis, higher Medicaid administration reimbursement rates would be positively associated with a greater likelihood of vaccine receipt among Medicaid eligible poor children, and (2) In the state-level analysis, Medicaid reimbursement rates would be positively associated with statewide influenza vaccination rates among Medicaid eligible poor children.

- Specifically, this study assessed influenza vaccination rates among nationally representative children aged 6-23 months during the 2005-2006, 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 influenza seasons, using the U.S. National Immunization Surveys (NIS) (weighted N=3.3 - 4.0 million per season). This study categorized children into three income levels (poor, near-poor, non-poor), where poor children represented those who were Medicaid eligible (in all states based on federal poverty level below 100%). This study implemented cross-sectional multivariable logistic regression analyses where full influenza vaccination was the dependent variable. The key covariates were the state Medicaid reimbursement rate (a continuous variable, ranging from $2 to $17.86 per vaccination) and its interaction terms with income levels. Other covariates included twelve individual factors and four state-level factors.

- Altogether, 21.0%, 21.3%, and 28.9% of all U.S. children and 11.7%, 11.6%, and 18.8% of poor children were fully vaccinated during the 2005-2006, 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 influenza seasons, respectively. As shown in Table 1 (row 3), this study's multivariable analyses found a positive and significant (all p<0.05) association between state-level Medicaid reimbursement and influenza vaccination rates among poor children, which was robust in all three seasons. The magnitude of this association is substantial. If a Medicaid program increased the reimbursement rate by ten dollars - the difference between the U.S. average ($8 per influenza vaccination) and the highest state reimbursement ($18) - the increase was expected to raise the full vaccination rate among poor children by 6.0, 9.2 and 6.4 percentage points at the state-level during the 2005-2006, 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 influenza seasons, respectively.

- A potential policy implication, based on these empirical results, is to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates that could improve vaccine coverage among Medicaid eligible poor children. The VFC program, providing free vaccines for Medicaid eligible children, was reported to be associated with a reduction in physician referrals to health departments and also with rising overall vaccination rates [41,42]. However, the VFC program alone does not seem adequate for providers who remain at financial risk due to inadequate reimbursement to cover vaccine administration costs.

- IV. System Factor: Vaccine Supply Effect on Racial/Ethnic Disparity

- There were five seasons of influenza vaccine supply problem (delay, shortage or both) in the U.S. since 2000 (CDC. Cumulative monthly U.S. influenza vaccine distribution, 1999-2006, Unpublished data, 2006) [43]. During these five seasons, influenza vaccine coverage rates in the U.S. tended to be lower [44-46]. Approximately 15% of the U.S. Medicare beneficiaries experienced difficulties in receiving an influenza vaccination, due to the limited influenza vaccine availability [45], and many high-priority groups did not seek vaccination because of their perception of an influenza vaccine shortage during the 2004-2005 season [47]. Despite recent progress in bolstering the production capacity of the U.S. influenza vaccine market [48], inadequacies in supply remain due to the uncertainty regarding regulation compliance by manufacturers [49].

- A number of studies tested a hypothesis that disparities in influenza vaccination will be exacerbated when vaccine supply declines or is delayed [17,50]. This is because vulnerable populations, such as underserved racial and ethnic populations, may face relatively greater barriers to accessing limited vaccines during such seasons with vaccine supply problem. Link et al. reported no significant change in disparities by race or ethnicity among the adults aged 65 or older during the 2004-2005 season compared to prior seasons based on their analysis of the U.S. nationally representative Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) dataset [50].

- A methodological limitation of the study by Link et al. motivated the study by the author and colleagues. Their limitation was due to the design of BRFSS datasets, collecting a different set of subjects every year and hence only enabling a cross-sectional analysis. However, a cross-sectional analysis is unable to adequately adjust for potential time-varying confounders (e.g., vaccine supply, health status and any unobservable factors) that may disproportionally affect persons in each racial/ethnic group. A cohort analysis can address this issue more appropriately. This is because potentially confounding variables within the same subjects are likely to change relatively little between two consecutive seasons.

- Therefore, the study by the author and colleagues [17] implemented a cohort analysis of subjects followed over two consecutive seasons with different levels of vaccine supply. Specifically, this study conducted cross-sectional multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine whether racial/ethnic disparities in vaccination rates changed across two consecutive seasons: from (period 1) 2000-2001 and 2001-2002 seasons through (period 4) 2003-2004 and 2004-2005 seasons. The dependent variable was self-reported receipt of influenza vaccine across consecutive years among the U.S. nationally representative community dwelling non-Hispanic African-American (AA), non-Hispanic White (W), English-speaking Hispanic (EH) and Spanish-speaking Hispanic (SH) elderly, who were enrolled in the MCBS (weighted N = 8.23 - 8.99 million for periods 1-4). Independent variables included three racial/ethnic categories and sixteen individual level factors.

- The main findings are presented in Table 1 (bottom row). When vaccine supply increased nationally during periods 1 and 2, adjusted racial/ethnic disparities in the influenza vaccination coverage rate decreased by 1.8-7.4% (W-AA disparity), 4.5-6.6% (W-EH disparity) and 6.6-11% (W-SH disparity) (all p<0.001). On the other hand, when vaccine supply declined during period 4, adjusted disparities in vaccination coverage rates increased by 2.3% (W-AA disparity) and 6.1% (W-EH disparity).

- Therefore, this paper concluded that improved vaccine supply was generally associated with narrowed or improved racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination rates and that reduced supply was associated with widened or worsened disparities. In order to avoid future widening of racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination rates, policy implications include stabilization of the vaccine supply and preferential delivery of vaccines to safety-net providers serving vulnerable population such as AA and Hispanic populations during a vaccine supply shortage.

POTENTIAL DETERMINANTS OF INFLUENZA VACCINE RECEIPT

- In order to improve influenza vaccination coverage rates regarding both the overall rates and the disparities across subpopulations, multi-dimension policies (suggested by our conceptual model in Figure 1) seem to be needed. In addition, as adopted in the studies introduced in this paper, the analysis of nationally representative populations and the utilization of rigorous methodologies are needed to provide policy implications which are generalizable at a national level and probably in other countries.

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

-

This article is available at http://jpmph.org/.

Notes

- 1. Influenza (seasonal) factsheet 2009. World Health Organization. cited 2011 May 23. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/index.html

- 2. Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler GL, Singleton JA, et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59(RR-8):1-62. 20689501

- 3. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 2003;289(2):179-186. 12517228ArticlePubMed

- 4. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 2004;292(11):1333-1340. 15367555ArticlePubMed

- 5. Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, et al. Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008;57(RR-7):1-60. 18685555

- 6. OECD health data 2010: health care activities -- vaccination rates against influenza for people 65 and, over. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2010. cited 2011 May 22. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/topic/0,3699,en_2649_37407_1_1_1_1_37407,00.html

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination levels among persons aged > or = 65 years -- United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50(25):532-537. 11446571PubMed

- 8. Endrich MM, Blank PR, Szucs TD. Influenza vaccination uptake and socioeconomic determinants in 11 European countries. Vaccine 2009;27(30):4018-4024. 19389442ArticlePubMed

- 9. Fiscella K. Commentary--anatomy of racial disparity in influenza vaccination. Health Serv Res 2005;40(2):539-549. 15762906ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Hebert PL, Frick KD, Kane RL, McBean AM. The causes of racial and ethnic differences in influenza vaccination rates among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res 2005;40(2):517-537. 15762905ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Healthy people 2020,immunization and infectious diseases, objectives. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. USDHHS. 2010. cited 2011 May 25. Available from: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=23

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine-preventable diseases: improving vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. A report on recommendations from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep 1999;48(RR-8):1-15

- 13. Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, Shefer AM, Strikas RA, Bernier RR, et al. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(1 Suppl):97-140. 10806982Article

- 14. Yoo BK, Kasajima M, Fiscella K, Bennett NM, Phelps CE, Szilagyi PG. Effects of an ongoing epidemic on the annual influenza vaccination rate and vaccination timing among the Medicare elderly: 2000-2005. Am J Public Health 2009;99(Suppl 2):S383-S388. 19797752ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Yoo BK, Berry A, Kasajima M, Szilagyi PG. Association between Medicaid reimbursement and child influenza vaccination rates. Pediatrics 2010;126(5):e998-e1010. 20956412ArticlePubMed

- 16. Yoo BK, Holland ML, Bhattacharya J, Phelps CE, Szilagyi PG. Effects of mass media coverage on timing and annual receipt of influenza vaccination among Medicare elderly. Health Serv Res 2010;45(5 Pt 1):1287-1309. 20579128ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Yoo BK, Kasajima M, Phelps CE, Fiscella K, Bennett NM, Szilagyi PG. Influenza vaccine supply and racial/ethnic disparities in vaccination among the elderly. Am J Prev Med 2011;40(1):1-10. 21146761ArticlePubMed

- 18. Fiore AE, Shay DK, Haber P, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, et al. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2007. MMWR Recomm Rep 2007;56(RR-6):1-54. 17625497

- 19. Schuchat A. U.S. passes million swine flu cases, officials say. The New York Times. 2009. 6. 27

- 20. Mullahy J. It'll only hurt a second? Microeconomic determinants of who gets flu shots. Health Econ 1999;8(1):9-24. 10082140ArticlePubMed

- 21. Li YC, Norton EC, Dow WH. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination demand responses to changes in infectious disease mortality. Health Serv Res 2004;39(4 Pt 1):905-925. 15230934ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Yoo BK, Frick K. Determinants of influenza vaccination timing. Health Econ 2005;14(8):777-791. 15700301ArticlePubMed

- 23. Iwane MK, Singleton JA, Walton K, Coulen C, Wooten K. Assessing influenza vaccine utilization in physician offices serving adult patients: experience during a season of vaccine delays and shortages. J Public Health Manag Pract 2007;13(3):307-313. 17435498ArticlePubMed

- 24. Flu activity & surveillance 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). cited 2008 May 18. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivity.htm

- 25. Grilli R, Ramsay C, Minozzi S. Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD000389. 11869574ArticlePubMed

- 26. Brodie M, Hamel EC, Altman DE, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Health news and the American public, 1996-2002. J Health Polit Policy Law 2003;28(5):927-950. 14604217ArticlePubMed

- 27. Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J, Cowen ME, Carpenter D, Vijan S. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(13):1601-1605. 12860585ArticlePubMed

- 28. Schade CP, McCombs M. Do mass media affect Medicare beneficiaries' use of diabetes services? Am J Prev Med 2005;29(1):51-53. 15958252ArticlePubMed

- 29. Daley MF, Crane LA, Chandramouli V, Beaty BL, Barrow J, Allred N, et al. Influenza among healthy young children: changes in parental attitudes and predictors of immunization during the 2003 to 2004 influenza season. Pediatrics 2006;117(2):e268-e277. 16452334ArticlePubMed

- 30. Gnanasekaran SK, Finkelstein JA, Hohman K, O'Brien M, Kruskal B, Lieu T. Parental perspectives on influenza vaccination among children with asthma. Public Health Rep 2006;121(2):181-188. 16528952ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 31. Ma KK, Schaffner W, Colmenares C, Howser J, Jones J, Poehling KA. Influenza vaccinations of young children increased with media coverage in 2003. Pediatrics 2006;117(2):e157-e163. 16452325ArticlePubMed

- 32. Vaccines for Children Program (VFC): for parents. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2009. cited 2011 June 6. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/parents/default.htm

- 33. Yoo BK, Szilagyi PG, Schaffer SJ, Humiston SG, Rand CM, Albertin CS, et al. Cost of universal influenza vaccination of children in pediatric practices. Pediatrics 2009;124(Suppl 5):S499-S506. 19948581ArticlePubMed

- 34. Coleman MS, Lindley MC, Ekong J, Rodewald L. Net financial gain or loss from vaccination in pediatric medical practices. Pediatrics 2009;124(Suppl 5):S472-S491. 19948579ArticlePubMed

- 35. Glazner JE, Beaty B, Berman S. Cost of vaccine administration among pediatric practices. Pediatrics 2009;124(Suppl 5):S492-S498. 19948580ArticlePubMed

- 36. Santibanez TA, Santoli JM, Bridges CB, Euler GL. Influenza vaccination coverage of children aged 6 to 23 months: the 2002-2003 and 2003-2004 influenza seasons. Pediatrics 2006;118(3):1167-1175. 16951012ArticlePubMed

- 37. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza vaccination coverage among children aged 6-23 months--United States, 2005-06 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(37):959-963. 17882125PubMed

- 38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza vaccination coverage among children aged 6--59 months --- eight immunization information system sentinel sites, United States, 2007-08 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57(38):1043-1046. 18818584PubMed

- 39. Fairbrother G, Hanson KL, Friedman S, Butts GC. The impact of physician bonuses, enhanced fees, and feedback on childhood immunization coverage rates. Am J Public Health 1999;89(2):171-175. 9949744ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Szilagyi PG, Shone LP, Barth R, Kouides RW, Long C, Humiston SG, et al. Physician practices and attitudes regarding adult immunizations. Prev Med 2005;40(2):152-161. 15533524ArticlePubMed

- 41. Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Pollard Shone L, Kolasa MS, Rodewald LE. Decline in physician referrals to health department clinics for immunizations: the role of vaccine financing. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(4):318-324. 10788735ArticlePubMed

- 42. Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Shone LP, Barth R, Kolasa MS, Rodewald LE. Impact of vaccine financing on vaccinations delivered by health department clinics. Am J Public Health 2000;90(5):739-745. 10800422ArticlePubMedPMC

- 43. Wallace GS. Influenza vaccine distribution 2006-07. 2007. 2. 05. National Vaccine Advisory Committee, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- 44. Layton C, Robinson T, Honeycutt A. Influenza vaccine demand: the chicken and the egg, Issue brief, 2005. 2005. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; RTI Project No. 0208665.001. Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/pic/fullreports/06/8476-4.doc

- 45. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare current beneficiary survey: CY 2000-2006. 2006. Baltimore, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services

- 46. Rodewald LE, Orenstein WA, Mason DD, Cochi SL. Vaccine supply problems: a perspective of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42(Suppl 3):S104-S110. 16447130ArticlePubMed

- 47. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Experiences with obtaining influenza vaccination among persons in priority groups during a vaccine shortage -United States, October--November, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53(49):1153-1155. 15614228ArticlePubMed

- 48. Orenstein WA, Schaffner W. Lessons learned: role of influenza vaccine production, distribution, supply, and demand--what it means for the provider. Am J Med 2008;121(7 Suppl 2):S22-S27. 18589064Article

- 49. Danzon PM, Pereira NS, Tejwani SS. Vaccine supply: a cross-national perspective. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(3):706-717. 15886165ArticlePubMed

- 50. Link MW, Ahluwalia IB, Euler GL, Bridges CB, Chu SY, Wortley PM. Racial and ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination coverage among adults during the 2004-2005 season. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163(6):571-578. 16443801ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure 1

Conceptual model of vaccination.

Factors in bold are detailed with key references [14-17] in the main text and Table 1.

Table 1.Summary of potential determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination

| Factor in (Figure 1) | Potential determinants: key finding | Study population | Policy implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemic factor | Ongoing short-tem (weekly) epidemic level, positively associated with vaccine receipt [14] | U.S. nationally-representative Medicare elderly enrolled in Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) (5 seasons: 2000- 2005) [14] | To help predict short-term, late-season vaccine demand, enabling better seasonal influenza vaccine distribution and redistribution, thus improving the overall vaccine coverage rate [14]. |

| Patient factor | Mass media report on influenza and vaccine supply problem, positively associated with vaccine receipt. | U.S. nationally-representative Medicare elderly enrolled in MCBS (3 seasons: 1999-2001) [16] | To conduct vaccination campaigns using mass media (newspapers or television) effectively: (i) using a headline, as well as text, which include specific key words like shortage/delay in addition to influenza alone, (ii) performing repeated media campaign use rather than one-time use, because of the suggested short-term media effect and the cumulative effects during a period, and (iii) securing adequate vaccine supply prior to a media campaign release on supply delay/shortage due to individuals’quick response to such release [16]. |

| Mass media report measured by the number of television program transcripts (in 4 major networks of ABC, CBS, FOX and NBC) and national newspaper/wire service articles (USA Today and Associated Press) [16] | |||

| Provider factor | Medicaid reimbursement rate for administering vaccination, positively associated with vaccine receipt [15] | U.S. nationally-representative children aged 6-23 months enrolled in National Immunization Survey (NIS) (3 seasons: 2005- 2008) [15] | To increase Medicaid reimbursement rates that could improve vaccine coverage among Medicaid eligible poor children [15]. |

| System factor | Improved vaccine supply was generally associated with narrowed or improved racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination rates. Reduced supply was associated with widened or worsened disparities [17] | U.S. nationally-representative Medicare elderly enrolled in MCBS (4 seasons: 2000-2005) [17] | To stabilize the vaccine supply and preferential delivery of vaccines to safety-net providers serving vulnerable population such as racial/ethnic minority populations during a vaccine supply shortage [17]. |

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- A Description of Theoretical Models for Health Service Utilization: A Scoping Review of the Literature

Jordan A. Gliedt, Antoinette L. Spector, Michael J. Schneider, Joni Williams, Staci Young

INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing.2023; 60: 004695802311768. CrossRef - Low Levels of Influenza Vaccine Uptake among the Diabetic Population in Spain: A Time Trend Study from 2011 to 2020

Jose J. Zamorano-Leon, Rodrigo Jimenez-Garcia, Ana Lopez-de-Andres, Javier de-Miguel-Diez, David Carabantes-Alarcon, Romana Albaladejo-Vicente, Rosa Villanueva-Orbaiz, Khaoula Zekri-Nechar, Sara Sanz-Rojo

Journal of Clinical Medicine.2021; 11(1): 68. CrossRef - Influenza vaccination among U.S. pediatric patients receiving care from federally funded health centers

Lydie A. Lebrun-Harris, Judith A. Mendel Van Alstyne, Alek Sripipatana

Vaccine.2020; 38(39): 6120. CrossRef - Emerging respiratory infections threatening public health in the Asia‐Pacific region: A position paper of the Asian Pacific Society of Respirology

Sunghoon Park, Ji Young Park, Yuanlin Song, Soon Hin How, Ki‐Suck Jung

Respirology.2019; 24(6): 590. CrossRef - Exploring Disparities in Influenza Immunization for Older Women

Sarah MacCarthy, Q Burkhart, Amelia M. Haviland, Jacob W. Dembosky, Shondelle Wilson‐Frederick, Debra Saliba, Sarah Gaillot, Marc N. Elliott

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.2019; 67(6): 1268. CrossRef - Optimal Design of the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine with Manufacturing Autonomy

Osman Y. Özaltın, Oleg A. Prokopyev, Andrew J. Schaefer

INFORMS Journal on Computing.2018; 30(2): 371. CrossRef - Preventive Effects of Vitamin D on Seasonal Influenza A in Infants: A Multicenter, Randomized, Open, Controlled Clinical Trial

Jian Zhou, Juan Du, Leting Huang, Youcheng Wang, Yimei Shi, Hailong Lin

Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.2018; 37(8): 749. CrossRef - Factors Influencing Vaccination in Korea: Findings From Focus Group Interviews

Bomi Park, Eun Jeong Choi, Bohyun Park, Hyejin Han, Su Jin Cho, Hee Jung Choi, Seonhwa Lee, Hyesook Park

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health.2018; 51(4): 173. CrossRef - Prioritizing high-risk sub-groups in a multi-manufacturer vaccine distribution program

Sharon Hovav, Avi Herbon

The International Journal of Logistics Management.2017; 28(2): 311. CrossRef - Patterns of influenza vaccination coverage in the United States from 2009 to 2015

Alice P.Y. Chiu, Jonathan Dushoff, Duo Yu, Daihai He

International Journal of Infectious Diseases.2017; 65: 122. CrossRef - Estrategias para mejorar la cobertura de la vacunación antigripal en Atención Primaria

F. Antón, M.J. Richart, S. Serrano, A.M. Martínez, D.F. Pruteanu

SEMERGEN - Medicina de Familia.2016; 42(3): 147. CrossRef - Efforts to Improve Immunization Coverage during Pregnancy among Ob-Gyns

Katherine M. Jones, Sarah Carroll, Debra Hawks, Cora-Ann McElwain, Jay Schulkin

Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology.2016; 2016: 1. CrossRef - Association of influenza vaccine uptake with health, access to health care, and medical mistreatment among adults from low-income neighborhoods in New Haven, CT: A classification tree analysis

Kathryn Gilstad-Hayden, Amanda Durante, Valerie A. Earnshaw, Lisa Rosenthal, Jeannette R. Ickovics

Preventive Medicine.2015; 74: 97. CrossRef - Decomposing racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination among the elderly

Byung-Kwang Yoo, Takuya Hasebe, Peter G. Szilagyi

Vaccine.2015; 33(26): 2997. CrossRef - Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of a Television Campaign to Promote Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Among the Elderly

Minchul Kim, Byung-Kwang Yoo

Value in Health.2015; 18(5): 622. CrossRef - Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Obstetrician-Gynecologists Regarding Influenza Prevention and Treatment Following the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic

Katie L. Murtough, Michael L. Power, Jay Schulkin

Journal of Women's Health.2015; 24(10): 849. CrossRef - Effectiveness of hospital-based postpartum procedures on pertussis vaccination among postpartum women

Sylvia Yeh, ChrisAnna Mink, Matthew Kim, Scott Naylor, Kenneth M. Zangwill, Norma J. Allred

American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.2014; 210(3): 237.e1. CrossRef - Can Routine Offering of Influenza Vaccination in Office-Based Settings Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Adult Influenza Vaccination?

Jürgen Maurer, Katherine M. Harris, Lori Uscher-Pines

Journal of General Internal Medicine.2014; 29(12): 1624. CrossRef - Influenza Vaccination Coverage among Adults in Korea: 2008–2009 to 2011–2012 Seasons

Hye Yang, Sung-il Cho

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.2014; 11(12): 12162. CrossRef - Faible taux de couverture vaccinale contre la grippe des sujets âgés hospitalisés en France

E. Rouveix, S. Greffe, C. Dupont, D. Gherissi Cherni, A. Beauchet, H. Sordet Guepet, G. Gavazzi, J. Gaillat

La Revue de Médecine Interne.2013; 34(12): 730. CrossRef

KSPM

KSPM

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite