Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Prev Med Public Health > Volume 55(6); 2022 > Article

-

Original Article

Effectiveness of a Social Marketing Mix Intervention on Changing the Smoking Behavior of Santri in Traditional Islamic Boarding Schools in Indonesia -

Ismail Ismail1

, Teuku Tahlil2

, Teuku Tahlil2 , Nursalam Nursalam3

, Nursalam Nursalam3 , Zurnila Marli Kesuma4

, Zurnila Marli Kesuma4 , Syarifah Rauzhatul Jannah5

, Syarifah Rauzhatul Jannah5 , Hajjul Kamil6

, Hajjul Kamil6 , Fithria Fithria7

, Fithria Fithria7 , Kintoko Rochadi8

, Kintoko Rochadi8

-

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2022;55(6):586-594.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.22.231

Published online: November 17, 2022

- 3,605 Views

- 187 Download

1Department of Nursing, Polytechnic of Health, Ministry of Health, Aceh, Indonesia

2Department of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Aceh, Indonesia

3Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

4Department of Statistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Aceh, Indonesia

5Department of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Aceh, Indonesia

6Department of Leadership and Management Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Aceh, Indonesia

7Department of Family Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Aceh, Indonesia

8Faculty of Public Health, University of North Sumatra, Medan, Indonesia

- Corresponding author: Teuku Tahlil, Department of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Aceh 23111, Indonesia E-mail: ttahlil@unsyiah.ac.id

Copyright © 2022 The Korean Society for Preventive Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Objectives:

- This study investigated the effectiveness of the social marketing mix approach in increasing students’ knowledge about smoking, promoting positive attitudes toward smoking cessation, and decreasing smoking behavior.

-

Methods:

- This quantitative research study incorporated a quasi-experimental method with a pretest-posttest non-equivalent group design. Using the purposive sampling technique, 152 smoking students were selected as participants. They were divided into 2 equal groups, with 76 students in the control group and 76 in the intervention group. The data were collected using questionnaires and analyzed with the chi-square test, independent t-test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and Mann-Whitney U-test.

-

Results:

- The social marketing mix intervention was effective in increasing the students’ knowledge about smoking (p<0.001), improving their attitude toward smoking cessation (p<0.001), and reducing their smoking behavior (p=0.014).

-

Conclusions:

- This approach should be implemented by local governments to reduce smoking behavior in the community, especially among teenagers, in addition to instituting a smoking ban and applying fines.

- Smoking behavior among santri (students at Islamic boarding schools in Indonesia) is very concerning. At cultural or religious events, nearly all santri smoke cigarettes. Teaching staff (teungku), who are religious role models in Acehnese culture, ironically also smoke. Students often follow or imitate their behavior, including smoking [1]. Existence in a smoking environment is a major factor influencing adolescents to smoke [2]. The pesantren, or Islamic boarding school, often becomes a smoking environment. This commonly influences non-smoking students to become smokers as well. Furthermore, the practice is considered normal, even by the pesantren’s leaders and teachers, who accordingly do not prohibit smoking. Cigarettes are also widely available for sale around the pesantren. In previous research, students have admitted that they can buy cigarettes easily and smoke them anywhere in the pesantren. They have also reported not receiving any information about the health dangers of smoking [1].

- The smoking behavior of adolescents is related to factors including cigarette advertisements, lack of awareness of smoking risks, attitudes towards smoking, trust factors, the influence of smoking peers, socioeconomic background, perceptions of parents and teachers who smoke, and smoking control policies [3-5]. Smoking behavior among adolescents can greatly affect their productivity and quality of life [2].

- The World Health Organization has reported that tobacco products kill up to half of their users. More than 7 million annual deaths are caused by direct smoking, and approximately 1.2 million deaths occur due to exposure to secondhand smoke [6]. According to World Health Organization data, Indonesia has the highest prevalence of smoking in the world (76.2%), and the prevalence among 10-year-olds to 18-year-olds increased from 7.2% in 2013 to 9.1% in 2018. More than half of smokers (52.3%) smoke 1 to 10 cigarettes per day. The most common age range of first smoking in Indonesia’s Aceh Province was reported to be 15-19 years (53.5%) [7].

- Smoking behavior can be avoided if the individual is strongly committed not to smoke. Attitudes, subjective norms, and self-perceptions are some of the factors that can be changed [8]. Several studies have shown significant results after interventions to prevent smoking behavior. Educational intervention typically incorporates mass media by applying the health belief model, health literacy, and peer education [9-11]. Another intervention methodology, termed a social marketing mix, is designed to increase individual health-related knowledge and induce behavioral changes. The social marketing mix strategy consists of 4 elements: product, price, place, and promotion. In a mutually supportive manner, each element reinforces the overall message [12].

- Social marketing mix interventions have been widely used to change health behaviors, such as in preventing HIV/AIDS [13,14], reducing salt intake [15], and increasing individual awareness of the risks of drug use [16]. However, research on the application of the social marketing mix strategy to change smoking behavior is still limited. Therefore, this study was carried out to investigate the effectiveness of the social marketing mix in increasing knowledge about smoking, improving positive attitude toward smoking cessation, and changing the smoking behavior of the santri at 2 traditional Islamic boarding schools in Aceh Besar, Indonesia.

INTRODUCTION

- Research Design

- In this quasi-experimental study, a pretest-posttest nonequivalent group design was used. The participants in this study were a total of 152 smoking students in 2 pesantren. They were selected using the purposive sampling technique based on the following criteria: aged 10-24 years, displayed smoking behavior, and had stayed at the boarding school for at least 1 year. Participants were divided equally into 2 groups, with 76 in the intervention group and 76 in the control group. The pesantren at which the research was conducted were selected based on permission from the Dayah Agency of Aceh Besar district, and the pesantren were then randomized using Google’s number generator procedure to determine which would be used as the intervention group and which would be used as the control group.

- During the implementation of the intervention and post-test, 7 students from the intervention group and 6 students from the control group did not participate and were thus excluded from further study.

- Research Instrument

- The questionnaire was prepared based on a literature review and the results of interviews that the researchers had previously conducted [17]. Then, the questionnaire was tested for validity and reliability using 30 students at different Islamic boarding schools where that previous research was conducted.

- The data collected from the respondents consisted of age (based on their last birthday), year of education, length of time as a student of the boarding school (in years), father’s and mother’s educational background, father’s and mother’s occupation, smoking status of their parents, smoking status of their peers, amount of daily spending money (in rupiah), age of first smoking (in years), reasons for smoking, and types of cigarettes smoked.

- The students’ knowledge about smoking was evaluated through 30 true-or-false statements in the questionnaire. The statements were related to smoking laws based on the Al-Quran and Hadith, the fatwa (Islamic legal thought) of the Indonesian Ulama Council on smoking, the Qanun of Kawasan Tanpa Rokok of the Aceh government, and the dangers of smoking to health. A value of 1 was assigned for each correct answer, while 0 was given for each wrong answer. The total score ranged from 0 to 30, with higher values indicating greater knowledge. This questionnaire was previously tested for validity and reliability, with a Cronbach alpha value of 0.89 for the knowledge variable.

- Attitudes of students towards smoking were measured through 15 positive statements in a Likert-scale questionnaire. The questionnaire had 4 levels: strongly disagree (score 1), disagree (score 2), agree (score 3), and strongly agree (score 4). The results of the validity test and the questionnaire reliability test showed that the Cronbach alpha value for the attitude variable was 0.80. The lowest possible total score for the attitude variable was 15, and the highest was 60.

- Smoking behavior in this study was measured through a single question: “What is the average number of clove cigarettes/white/rolled cigarettes you smoke per day?” This question was adopted from the 2018 Basic Health Research questionnaire of the Indonesian Ministry of Health (No. G12) [7].

- Intervention Program

- Before developing the intervention program, the researchers conducted in-depth interviews to identify whether the social marketing mix method could be applied at the schools to change the students’ smoking behavior. The interviews were conducted with the leaders of the pesantren, teaching staff (teungku), boarding school guards, members of the local government, members of religious departments, santri, parents of santri (fathers and mothers), affiliates of the public health center, members of the Aceh Ulama Consultative Council, and cigarette vendors around the pesantren. A total of 25 participants were involved in the interviews. The interview results were then used as the basis to develop the intervention module. Details of the interviews and intervention module development were described in previous research publications [17].

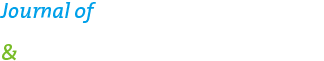

- The social marketing mix intervention was administered only to the students in the intervention group. It consisted of 6 intervention sessions, each lasting 45 minutes. In each session, the intervention comprised 4 components: product, value, place, and promotion. Experts provided the students with materials for the product and value components, whereas for the place and promotion components, students received educational media.

- For the control group, the researchers did not provide any intervention during the research process. Rather, they simply collected data twice (through a pre-test and a post-test) and compared the results with those of the intervention group. However, after the post-test, the researchers presented a counseling session about the risks of smoking, explained the Islamic views on smoking, and distributed some booklets on smoking to the students.

- The implementation of the social marketing mix intervention in this study consisted of 6 phases: (1) Analysis: In this phase, an analysis was carried out to identify the social marketing mix model designed to change the smoking behavior of the students. (2) Strategy: During this phase, an intervention module consisting of 4 Ps (product, price, place, and promotion) was developed as the strategy to change the students’ smoking behavior. (3) Program and communication design: This phase involved consulting the modules that have been designed for experts and testing the questionnaires that would be used in the study. (4) Pre-testing: This phase (which took 20-25 minutes) was carried out 1 week before the first intervention session. (5) Implementation: This phase included all components of the social marketing mix; It consisted of 6 meetings, with the first intervention carried out 1 week after the pre-test and each subsequent session delivered 1 week after the previous intervention; Each session took 45 minutes (30 minutes for giving the materials and 15 minutes for the question-and-answer session); The methods, materials, and interventions provided are shown in Table 1. (6) Data collection: The data were collected through a post-test 1 week after the completion of the sixth intervention session; The post-test was conducted by filling out the same questionnaire as that in the pre-test (again taking 20-25 minutes).

- Statistical Analysis

- This study involved descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. The statistical tests used were the chi-square test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the Mann-Whitney U-test, the independent t-test, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The chi-square test was utilized to understand the differences in the characteristics of the respondents between the control group and the intervention group based on categorical data. The Wilcoxon test was used to determine the differences between pre-test and post-test knowledge, attitudes, and smoking behavior for each group. The Wilcoxon test was utilized for this purpose because these data were not normally distributed. The Mann-Whitney test and independent t-test were used to determine the differences associated with the intervention for each research variable. The Mann-Whitney test was used when the data were not normally distributed and not homogeneous, while the independent t-test was used when the data were normally distributed and homogeneous. Finally, ANCOVA was used to determine the effect of the intervention on knowledge, attitudes, and smoking behavior after adjusting for other variables. The results of the homogeneity test using the Levene test showed that these data were homogeneous, so ANCOVA could be used.

- Ethics Statement

- This study aligned with the ethical principles of research, including anonymity, confidentiality, and beneficence. The approval of the santri and the owner of the pesantren was obtained through informed consent forms that were voluntarily completed. Ethical approval of the study was also obtained from the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Aceh Health Polytechnic with No. LB.02.03/5579/2020.

METHODS

Characteristics of the respondents

Knowledge about smoking

Attitudes towards smoking

Smoking behavior

Development of the intervention

Implementation of the intervention

- Characteristics of the Respondents

- The characteristics of the research respondents are shown in Table 2. A statistically significant difference was observed between the intervention and control groups (p<0.05) with regard to father’s occupation, age of first smoking, and duration of smoking. However, the groups did not differ significantly (p>0.05) in age, length of time as a student, amount of spending money, father’s and mother’s education, mother’s occupation, smoking parents, smoking peers, reasons for smoking, and types of cigarettes smoked.

- Knowledge, Attitudes, and Smoking Behavior of the Groups Before and After the Intervention

- Data regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and smoking behavior of the students in the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention are presented in Table 3.

- Table 3 shows the pre-test and post-test scores of the intervention group with regard to knowledge (p<0.001), attitude (p<0.001), and smoking behavior (p<0.001). The average score was greater after the social marketing mix intervention for both knowledge and attitude (knowledge=39.07; attitude=35.13), and the average decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked before and after the social marketing mix intervention was 31.86.

- In the control group, the difference between pre-test and post-test scores was also significant for knowledge (p<0.001), attitude (p<0.001), and smoking behavior (p=0.002). The average scores for knowledge and attitude increased (knowledge= 34.41; attitude=38.70), while the average decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked from pre-test to post-test was 31.26.

- Impacts of Social Marketing Mix Interventions on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Smoking Behavior

- The impacts of the social marketing mix intervention on the students’ knowledge, attitudes, and smoking behavior are shown in Table 4.

- Table 4 shows that no significant difference was found between the mean scores of the intervention group and the control group in the pre-test for knowledge (p=0.578), attitude (p=0.094), and smoking behavior (p=0.577). After the intervention, the mean score of the intervention group was significantly higher than that of the control group for knowledge (p<0.001) and attitude (p<0.001). In contrast, the mean score of the intervention group’s smoking behavior was significantly lower than that of the control group (p=0.014). This shows that the social marketing mix intervention was effective in increasing the knowledge and attitudes of the students as well as reducing the number of cigarettes smoked per day.

- Table 5 shows the influence of the intervention on the knowledge and attitudes of the adolescents (p<0.05). However, statistical testing indicated that age at first smoking, duration of smoking, and father’s occupation had no significant effect on adolescent knowledge and attitudes (p≥0.05). That is, the social marketing mix intervention increased the knowledge and attitudes of the adolescents, while the other factors had no significant influence. Regarding smoking behavior, changes in the number of cigarettes smoked per day were not only influenced by the social marketing mix intervention but also by age at first smoking and duration of smoking (Table 5).

RESULTS

- For both groups, a significant difference was observed between the pre-test and post-test mean scores of knowledge about smoking after the social marketing mix intervention was applied. However, the intervention group had a higher post-test level of knowledge than the control group. This indicates that the social marketing mix intervention was effective in increasing the students’ knowledge about smoking.

- Increased knowledge can help prevent smoking behavior, but it alone is not sufficient. People generally know that smoking is harmful to health, but they are often unaware of its specific dangers [18]. Intensive health advice from a health professional has been shown to increase the chance of quitting by 84% [19].

- Using the social marketing mix method, a program was developed to increase students’ knowledge about smoking prevention behavior. The social marketing mix methodology is generally used to minimize the constraints that a person faces in developing positive behaviors. The social marketing mix consists of the 4 P’s: place, product, price, and promotion [12].

- The social marketing mix intervention was designed as a single unit consisting of 4 components. The interventions included educational content as well as educational media and warning signs in support of smoking bans. In addition, the materials were delivered by experts to help the students gain a better understanding. Some of the speakers were role models for the students, and 1 had previously smoked and had quit due to a problem with his throat. The evidence provided by the speakers motivated the students to reduce the number of cigarettes they smoked.

- In the current study, the interventions incorporated the Indonesian Ulama Council’s fatwa regarding smoking bans as well as Islamic views on smoking based on the Qur’an and Hadith. These were found to be effective in increasing the students’ knowledge and reducing their smoking behavior. The fatwa was issued based on the fact that cigarettes cause many health problems, which violates the commands of the Qur’an and Hadith to maintain personal health and the health of others [18].

- In this study, no significant difference was observed between the intervention and control groups in the attitudes toward quitting smoking prior to the social marketing mix intervention. However, after the intervention group received the intervention, the difference between the 2 groups was statistically significant. Thus, the social marketing mix intervention was effective in increasing the attitudes of the students in the intervention group toward quitting smoking.

- The intervention strategy in this study was carried out to promote healthy living behavior. The social marketing mix program was designed to educate the students about the dangers of smoking and Islamic laws about smoking, leading to an increased desire of the students to quit smoking.

- In addition, the use of no-smoking signs may have contributed to the increase in the students’ attitude scores toward quitting smoking. The signs delivered a message that smoking is dangerous for health. This aligns with the research of Brewer et al. [20] revealing that pictorial warnings can enhance quitting attempts by eliciting an aversive reaction and keeping the message vivid in their memory.

- The application of the social marketing mix not only improved the knowledge and attitudes of the students but also reduced their smoking behavior. This is evidenced by the decrease in the number of cigarettes they smoked per day. The average number of daily cigarettes prior to the intervention was 8, which decreased to 5 cigarettes after the intervention. This baseline number was lower than the approximately 10 cigarettes per day noted as a baseline in the research of Paz Castro et al. [21]. However, it was higher than the baseline number in the research of Malik et al. [22], which was >5.

- In the context of health promotion, social marketing can be used to induce individual behavioral change. Designing an effective communication message, meeting the needs of the beneficiary, providing benefits that outweigh the cost, and being practical in achieving successful health promotion are important priorities in the social marketing mix. To improve the effectiveness of the social marketing mix, practitioners are also encouraged to design interesting media with messages about the benefits of behavioral change and a healthy lifestyle [23].

- Social marketing associated with smoking is an effective strategy to promote healthy attitudes and influence people to change health behaviors. It can influence smokers to voluntarily accept, reject, modify, or abandon their smoking behavior. Social marketing campaigns can strengthen knowledge and attitudes in favor of smoke-free laws, thereby helping to establish smoke-free norms [24]. In a study similar to the present research, a social marketing mix was applied in a smoking cessation campaign by involving middle and high-school students as agents on television and radio to help prevent smoking behavior. The results showed that most of the respondents attempted to influence others not to smoke [25].

- In the present study, intervention based on social marketing principles was effective in promoting a small yet statistically significant behavioral change. This review showed that the marketing mix, exchange strategy, and use of theory are significant factors that impact the effectiveness of the program on health behavioral change [26].

- During the implementation of the intervention, a non-smoking area was established and designed with stickers stating “no smoking” and advertising smoking fines. This has been found to be an effective strategy for changing smoking behavior. In a study in Lithuania, the implementation of smoking policies was successful [27]. An anti-smoking media campaign had a significant impact in support of a ban on indoor smoking. Mass media campaigns that contain important, positive, and negative messages have been shown to be effective in reducing smoking behavior [28,29].

- The present research was also consistent with previous findings in which a social marketing mix approach can increase individuals’ intentions not to use drugs [16]. Other research has also indicated that a social marketing campaign can provide an understanding of cancer risk factors to young people and adult men. It can also increase the awareness of the risks of being overweight, alcohol consumption, and poor intake of vegetables and fruits [30].

- One limitation of this study was that researchers did not directly observe the intensity of the students’ smoking behavior through the number of cigarettes they smoked. However, the questionnaire distributed to the students weekly helped the researchers collect data on their smoking behavior. Some uncontrollable factors existed, such as the presence of cigarette sellers around the Islamic boarding schools and environmental influences.

DISCUSSION

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

-

FUNDING

None.

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Ismail I, Tahlil T. Data curation: Nursalam N, Fithria F. Formal analysis: Kesuma ZM, Kamil H. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: Nursalam N, Jannah SR, Rochadi K. Writing – original draft: Ismail I. Writing – review & editing: Tahlil T, Nursalam N, Kesuma ZM, Jannah SR, Kamil H, Fithria F, Rochadi K.

Notes

| Characteristics | Intervention (n = 69) | Control (n = 70) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 18.41 | 18.10 | 0.5261 |

| Length of time as a student (y) | 4.73 | 5.24 | 0.1221 |

| Amount of spending money (rupiah/day) | 13 826.09 | 15 200.00 | 0.1261 |

| Father's education | 0.5362 | ||

| High | 13.0 | 15.7 | |

| Medium | 59.4 | 50.0 | |

| Low | 27.5 | 34.3 | |

| Mother's education | 0.3892 | ||

| High | 23.2 | 14.3 | |

| Medium | 49.3 | 57.1 | |

| Low | 27.5 | 28.6 | |

| Father's occupation | 0.0012 | ||

| Formal | 1.4 | 21.4 | |

| Informal | 98.6 | 77.1 | |

| None | 0.0 | 1.4 | |

| Mother's occupation | 0.2522 | ||

| Formal | 10.1 | 7.1 | |

| Informal | 55.1 | 44.3 | |

| None | 34.8 | 48.6 | |

| Smoking parents | 1.0002 | ||

| No | 52.2 | 52.9 | |

| Yes | 47.8 | 47.1 | |

| Smoking friends | 0.3402 | ||

| No | 39.1 | 47.1 | |

| Yes | 60.9 | 52.9 | |

| Age of first smoking (y) | 13.10 | 14.04 | 0.0021 |

| Duration of smoking (y) | 5.30 | 4.06 | 0.0231 |

| Reason for smoking | 0.8592 | ||

| To relieve stress | 7.2 | 4.3 | |

| To overcome boredom | 8.7 | 5.7 | |

| Association | 27.5 | 22.9 | |

| Feels difficult to quit | 4.3 | 5.7 | |

| Lack of awareness of the dangers | 33.3 | 40.0 | |

| Cigarettes are easily available | 18.8 | 21.4 | |

| Type of cigarettes smoked | 0.5562 | ||

| Clove cigarettes | 43.5 | 37.1 | |

| White cigarettes | 56.5 | 62.9 |

| Variables |

Intervention (n=69) |

Control (n=70) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean rank |

p-value1 |

Mean rank |

p-value1 | |||

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | |||

| Knowledge | ||||||

| Pre-test – post-test | 13.17 | 39.07 | <0.001 | 23.12 | 34.41 | <0.001 |

| Attitude | ||||||

| Pre-test – post-test | 9.83 | 35.13 | <0.001 | 12.73 | 38.70 | <0.001 |

| Smoking behavior | ||||||

| Pre-test – post-test | 31.86 | 12.29 | <0.001 | 31.26 | 19.37 | 0.002 |

| Variables | Intervention (n = 69) | Control (n = 70) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||

| Pre-test | 19.65±4.57 | 20.00±3.42 | 0.5781 |

| Post-test | 25.49±2.93 | 22.47±2.35 | <0.0011 |

| Attitude | |||

| Pre-test | 41.41±7.41 | 39.26±8.25 | 0.0942 |

| Post-test | 54.01±3.24 | 47.83±4.20 | <0.0011 |

| Smoking behavior | |||

| Pre-test | 8.36±5.06 | 7.93±4.66 | 0.5771 |

| Post-test | 5.68±2.92 | 6.90±3.08 | 0.0141 |

| Variables |

Post-test knowledge |

Post-test attitude |

Post -test smoking behavior |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type III sum of squares | p-value1 | Type III sum of squares | p-value1 | Type III sum of squares | p-value1 | |

| Intervention | 284.786 | <0.001 | 1139.161 | <0.001 | 32.55 | 0.040 |

| Age at first smoking (y) | 1.442 | 0.653 | 1.383 | 0.755 | 98.240 | <0.001 |

| Length of smoking (y) | 15.627 | 0.140 | 34.680 | 0.120 | 186.423 | <0.001 |

| Father's occupation | 0.262 | 0.848 | 2.624 | 0.667 | 10.138 | 0.250 |

| R squared | 0.259 | 0.419 | 0.210 | |||

- 1. Tahlil T, Kesuma dan ZM. Factors related to smoking behavior of students in Traditional pesantren Aceh Besar, Indonersian in 2018. Int J Med Sci Clin Invent 2019;6(6):4495-4500ArticlePDF

- 2. Setiana AD, Tahlil T. Factors environmental it is relationship with adolescents smoking behaviors in Aceh Besar. JIM Fkep 2017;2(3):1-5. (Indonesian)

- 3. Zainudin NZ, Philanderson AJ, Ci LJ, MZ NA, Baharom A. Prevalence and factors associated with cigarette smoking among adolescents of flat Pandamar Indah, Klang, Selangor. Int J Public Health Clin Sci 2018;5(6):178-189

- 4. Fernando HN, Wimaladasa IT, Sathkoralage AN, Ariyadasa AN, Udeni C, Galgamuwa LS, et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with tobacco smoking among adult males in Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health 2019;19(1):778ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 5. Jayawardhana J, Bolton HE, Gaughan M. The association between school tobacco control policies and youth smoking behavior. Int J Behav Med 2019;26(6):658-664ArticlePubMedPDF

- 6. World Health Organization. Tabacco; 2022 [cited 2022 May 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

- 7. Indonesian Ministry of Health. Indonesia basic health research 2018 [cited 2022 May 1]. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MRXC4lMDera5949ezbbHj7UCUj5_EQmY/view (Indonesian)

- 8. Nursalam. Research methodology in nursing science: a practical approach. 5th ed. Jakarta: Penerbit Salemba Medika; 2020. p. 87 (Indonesian)

- 9. Panahi R, Ramezankhani A, Tavousi M, Niknami S. Adding health literacy to the health belief model: effectiveness of an educational intervention on smoking preventive behaviors among university students. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.13773Article

- 10. Lim HL, Teh CH, Kee CC, Sumarni MG, Lim KH. A quasi experimental study on peer-based tobacco intervention to prevent smoking initiation among non-smoking secondary-school going male adolescents. Int J Public Health Clin Sci 2020;7(1):131-140

- 11. Thrasher JF, Huang L, Pérez-Hernández R, Niederdeppe J, Arillo-Santillán E, Alday J. Evaluation of a social marketing campaign to support Mexico City’s comprehensive smoke-free law. Am J Public Health 2011;101(2):328-335ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Lee NR, Kotler P. Social marketing: behavior change for social good. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2019. p. 33-34

- 13. Octavia A. The impact of social marketing mix and message effectiveness to target audience behavior of HIV/Aids. KnE Soc Sci 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v3i10.3357Article

- 14. Gibson DR, Zhang G, Cassady D, Pappas L, Mitchell J, Kegeles SM. Effectiveness of HIV prevention social marketing with injecting drug users. Am J Public Health 2010;100(10):1828-1830ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Layeghiasl M, Malekzadeh J, Shams M, Maleki M. Using social marketing to reduce salt intake in Iran. Front Public Health 2020;8: 207ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Soltani I, Mehranfar E. Tasyrabad social marketing mix on the prevention of drug abuse case study: (male secondary school students of Isfahan Province). Strateg Res Soc Probl Iran 2016;5(1):47-60. (Persian)

- 17. Ismail I, Tahlil T, Nurussalam N, Kesuma ZM. The application of social marketing to change smoking behavior of students in traditional Islamic boarding schools in Aceh. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2020;8(E):606-610ArticlePDF

- 18. Hussain M, Walker C, Moon G. Smoking and religion: untangling associations using English survey data. J Relig Health 2019;58(6):2263-2276ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. World Health Organization. Tobacco free initiative [cited 2022 May 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/about/how-we-work/programmes/tobacco-free-initiative

- 20. Brewer NT, Parada H, Hall MG, Boynton MH, Noar SM, Ribisl KM. Understanding why pictorial cigarette pack warnings increase quit attempts. Ann Behav Med 2019;53(3):232-243ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Paz Castro R, Haug S, Filler A, Kowatsch T, Schaub MP. Engagement within a mobile phone-based smoking cessation intervention for adolescents and its association with participant characteristics and outcomes. J Med Internet Res 2017;19(11):e356ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Malik M, Javed D, Hussain A, Essien EJ. Smoking habits and attitude toward smoking cessation interventions among healthcare professionals in Pakistan. J Family Med Prim Care 2019;8(1):166-170ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Liao CH. Evaluating the social marketing success criteria in health promotion: a F-DEMATEL approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(17):6317ArticlePubMedPMC

- 24. Khowaja LA, Khuwaja AK, Nayani P, Jessani S, Khowaja MP, Khowaja S. Quit smoking for life--social marketing strategy for youth: a case for Pakistan. J Cancer Educ 2010;25(4):637-642ArticlePubMedPDF

- 25. Schmidt E, Kiss SM, Lokanc-Diluzio W. Changing social norms: a mass media campaign for youth ages 12-18. Can J Public Health 2009;100(1):41-45ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 26. Hung CL. A meta-analysis of the evaluations of social marketing interventions addressing smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and eating [dissertation]. Bloomington: Indiana University; 2017

- 27. Klumbiene J, Sakyte E, Petkeviciene J, Prattala R, Kunst AE. The effect of tobacco control policy on smoking cessation in relation to gender, age and education in Lithuania, 1994-2010. BMC Public Health 2015;15: 181ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 28. Niederdeppe J, Kellogg M, Skurka C, Avery RJ. Market-level exposure to state antismoking media campaigns and public support for tobacco control policy in the United States, 2001-2002. Tob Control 2018;27: 177-184Article

- 29. Stead M, Angus K, Langley T, Katikireddi SV, Hinds K, Hilton S, et al. Mass media to communicate public health messages in six health topic areas: a systematic review and other reviews of the evidence. Public Health Res 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.3310/phr07080Article

- 30. Kippen R, James E, Ward B, Buykx P, Shamsullah A, Watson W, et al. Identification of cancer risk and associated behaviour: implications for social marketing campaigns for cancer prevention. BMC Cancer 2017;17(1):550ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KSPM

KSPM

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite