Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Prev Med Public Health > Volume 45(3); 2012 > Article

-

Special Article

Lessons From Healthcare Providers' Attitudes Toward Pay-for-performance: What Should Purchasers Consider in Designing and Implementing a Successful Program? - Jin Yong Lee1, Sang-Il Lee2, Min-Woo Jo2

-

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2012;45(3):137-147.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.3.137

Published online: May 31, 2012

1Department of Preventive Medicine, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea.

2Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- Corresponding author: Min-Woo Jo, MD, PhD. 88 Olympic-ro 43-gil, Songpa-gu, Seoul 138-736, Korea. Tel: +82-2-3010-4264, Fax: +82-2-477-2898, mdjominwoo@paran.com

Copyright © 2012 The Korean Society for Preventive Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

- We conducted a systematic review to summarize providers' attitudes toward pay-for-performance (P4P), focusing on their general attitudes, the effects of P4P, their favorable design and implementation methods, and concerns. An electronic search was performed in PubMed and Scopus using selected keywords including P4P. Two reviewers screened target articles using titles and abstract review and then read the full version of the screened articles for the final selections. In addition, one reference of screened articles and one unpublished report were also included. Therefore, 14 articles were included in this study. Healthcare providers' attitudes on P4P were summarized in two ways. First, we gathered their general attitudes and opinions regarding the effects of P4P. Second, we rearranged their opinions regarding desirable P4P design and implementation methods, as well as their concerns. This study showed the possibility that some healthcare providers still have a low level of awareness about P4P and might prefer voluntary participation in P4P. In addition, they felt that adequate quality indicators and additional support for implementation of P4P would be needed. Most healthcare providers also had serious concerns that P4P would induce unintended consequences. In order to conduct successful implementation of P4P, purchaser should make more efforts such as increasing providers' level of awareness about P4P, providing technical and educational support, reducing their burden, developing a cooperative relationship with providers, developing more accurate quality measures, and minimizing the unintended consequences.

- Pay-for-performance (P4P), which is a payment method that provides incentives to healthcare providers based upon the quality of their outcomes rather than simple healthcare service delivery [1], has been rapidly spreading across the world [2-6]. In the United States, this reimbursement method has been adopted not only in private markets such as the Integrated Healthcare Association [7] and Bridge to Excellence [8] but also in Medicare through the Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration Project [9] and Physician Group Practice Demonstration Project [10]. Among other western countries, the United Kingdom has applied a P4P program (Quality and Outcomes Framework) to contracts with general practitioners [11] and Australia has adopted the Practice Incentive Program to improve quality of care [12]. In addition, the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) in South Korea has also conducted a P4P demonstration project, the Value Incentive Program (VIP), for improving the quality of care for acute myocardial infarction and Caesarian section patients in the tertiary teaching hospitals since 2007 [2].

- Although many countries and health plans have adopted P4P programs, it is still controversial whether P4P is a successful strategy to increase the quality of care because the effectiveness of P4P and its primary target varies among programs. Many studies have reported positive effects of P4P on quality improvement [5,8,13-16]. However, on the other hand, several studies have raised questions such as the lack of effect [17,18], unintended consequences [16,19,20], disparities [21], ethical issues [22], and so on.

- Therefore, to create more successful P4P programs, purchasers (i.e., governments or health plans) should consider all aspects of P4P from its contemplation phase to final evaluation phase. To do this, Dudley and Rosenthal [23] presented P4P checklists, which included 20 questions for purchasers to consider in running P4P programs; these questions can be categorized into 4 stages according to which phase they relate to (contemplation, design, implementation, and evaluation phase).

- However, before doing this, the first step would be to gather providers' opinions toward P4P programs. This is very critical because healthcare providers are not merely primary stakeholders but also important players. The failure of financial incentives to increase cancer screening in Medicare managed care could be explained by a lack of physician awareness [17]. In addition, interventions in the practice site could improve healthcare quality in P4P [15]. Therefore, it would be difficult to implement P4P programs successfully without healthcare providers' support, and they could help to achieve P4P's goals. Also, providers' concerns can contain valuable information that can help purchasers redesign programs to have as positive an effect as possible on the quality of healthcare [23,24].

- We conducted a systematic review to summarize providers' attitudes toward P4P, focusing on their general attitudes, the effects of P4P, their favored design and implementation methods, and concerns. After the review, we will discuss what actions purchasers should take to make more successful P4P programs.

INTRODUCTION

- I. Operational Definition of Pay-for-performance

- There are various definitions for P4P for organizations. For example, "the use of payment methods and other incentives to encourage quality improvement and patient-focused high value care" [25]; "incentives (generally financial) to reward attainment of positive health results" [26]; and "transfer of money or material goods conditional on taking a measurable action or achieving a pre-determined performance target" [27]. In order to perform systematic review, we needed to identify our own definition of P4P. In this article, P4P was operationally defined by any kind of financial incentives or rewards to healthcare providers aiming to improve quality of care. That is, we decided to pay attention to the fact that "pay" refers to financial benefits from purchasers and "performance" means only quality performance (or outcome).

- II. Search Strategy

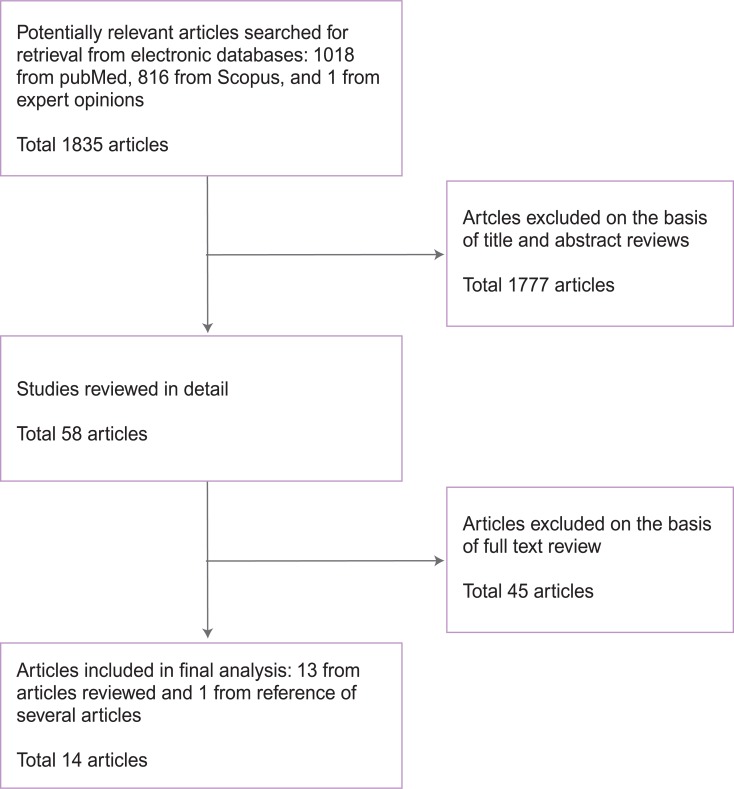

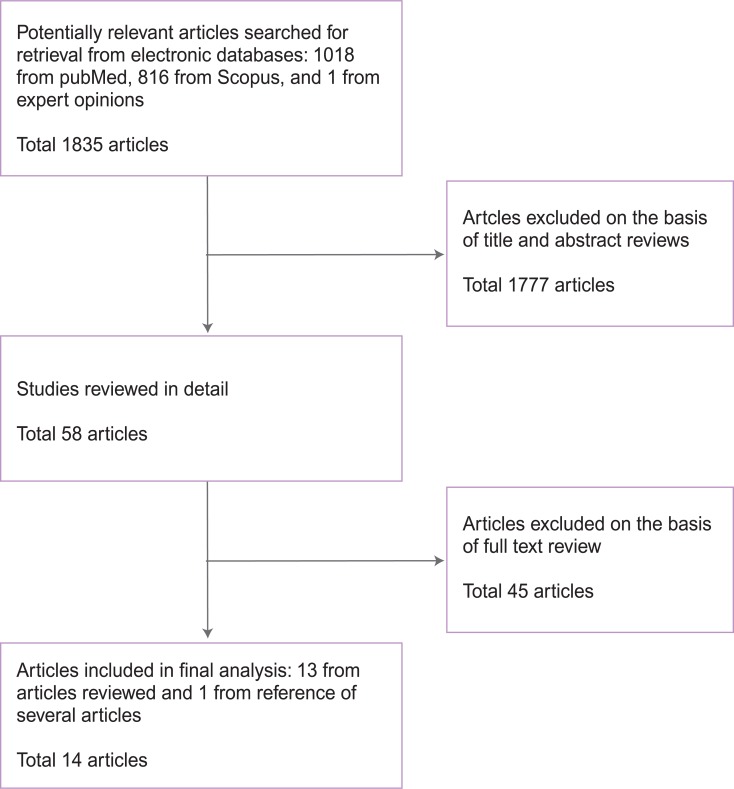

- A flow chart of the brief search strategy is shown in Figure 1. One librarian searched for published articles in two electronic databases, PubMed and Scopus, using selected key words. The electronic search was performed from 22 to 23, December, 2011 using the following keywords: pay for performance; incentive or reimbursement; performance or quality; payment or purchasing; health personnel, healthcare provider, physician, nurses, or hospital; attitude, behavior, position, or response; survey or questionnaires. Publication time and type were not limited. Two reviewers (Jo MW and Lee JY) screened target articles for analysis from results of electronic searches using titles and abstract review. Table 1 presents the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the target articles chosen by the reviewers. Then, two reviewers read the full version of the screened articles and chose the final articles. In addition, references and forward citations of screened articles were also searched without any time limitations. One unpublished report was also added by expert opinion. Disagreements on the final choice of articles were resolved by discussions on the operational definition of P4P among the authors. Because the objective of this study was not to draw a single conclusion, the quality and heterogeneity of studies were not used for exclusion criteria and just considered in discussions. Among 1835 articles from PubMed, Scopus, and expert opinion, on the basis of their title and abstract, 58 articles were selected for full-text review. This review process provided 14 articles eligible for our analysis: 13 from the reviewed articles and 1 mentioned in the reference lists of several reviewed articles.

- III. Summarization of Information

- General information from the studies was extracted from the 14 articles that were finally selected: citation, country, program, target and eligible population of study, study participants, and survey method (Table 2). Healthcare providers' attitudes on P4P were summarized in two ways (Tables 3 and 4). First, we gathered their general attitudes and opinions regarding the effects of P4P. General attitudes included three items: level of awareness, agreement or disagreement, and the reasons why they support or oppose P4P. Providers' opinions on the effects of P4P were reviewed in terms of their behavioral changes, effects on quality of care, and financial impact. Second, we rearranged their opinions regarding desirable P4P design and implementation methods, as well as their concerns. Because there were differences in the context including target population, design, or goal of P4P and the healthcare system, the original descriptions in the selected articles were used in this paper if possible.

METHODS

- I. Study Descriptions for Articles Included in the Final Analysis

- Table 2 shows the study descriptions including the first author and publication year, countries, the specific P4P program, target population, eligible bias, target population, and survey methods. Among the 14 studies, 11 studies were conducted in US and least 3 studies analyzed P4P in the US and UK, Korea, and Canada. The targets of the surveys were individual physicians in 6 studies, hospitals or physician organizations in 5 studies, and directors or physician executives in 2 studies. The total number of respondents in each study ranged from 16 to 1243. In a survey method, a mailed survey including postal service (6) was most common followed by interview (4), web-based survey including online questionnaire (3), fax (2), and poll (1).

- II. General Attitudes Toward P4P and Their Views on the Effects of P4P

- We summarized providers' general attitudes toward P4P and their view on the effects resulting from P4P (Table 3). Table 3 showed the possibility that some healthcare providers still have a low level of awareness about P4P [28-31]. For example, McDonald and Roland [28] indicated that many physicians were not aware of the target contents or had poor understanding of the relation between performance and incentives payments received. Also, Lee et al. [29] mentioned that the majority of healthcare providers did not know or understand what a P4P program was. Lastly, Young et al. [30] reported that physicians were fairly negative about their understanding of the details of P4P programs and the amount of incentive money being offered to them.

- We investigated why healthcare providers support or oppose P4P (Table 3). Their opinions varied according to their P4P settings. Proponents stated that 1) if the measures are accurate, physicians should be given financial incentives for quality [29,30,32,33]; 2) financial incentives are an effective way to improve the quality of healthcare [29,30,32]; 3) the benefits outweigh adverse consequences [34]; and 4) financial rewards are more effective as an incentive compared to non-financial rewards such as peer recognition [32]. However, opponents were concerned that 1) P4P will not lead to improved quality of care [31,35]; 2) they were skeptical that P4P would appropriately capture the quality of care [29,36]; 3) the incentive program was perceived as something externally imposed and managed, which made physicians feel that their autonomy was being challenged or that they were not trusted to perform in the absence of incentive payments [28]; 4) P4P could become a new method of government control over healthcare organization [29], and 5) P4P would result in unintended consequences [28,29,31-33,35-37].

- We have summarized the effects resulting from P4P program in terms of behavioral change, effect on quality of care, and financial impact in Table 3. Regarding behavioral change, some healthcare providers reported that they have changed their behaviors to meet the quality goals. These behavioral changes included the structural modification and process alteration at the physician or organization level. At the organizational level, for example, Pines et al. [35] reported a number of operational changes that are being implemented to improve time to antibiotics for pneumonia. Also, Damberg et al. [34] reported that P4P has directly affected organizational behaviors by increasing accountability for quality, influencing the speed of IT adoption for quality management, and creating greater organizational focus and support for quality programs and goals. In addition, other studies indicated that structure and process change to reach the quality standard occurred at the organizational level [29,38]. At the physician level, even though three studies reported that physicians changed their behaviors to obtain financial incentives [28,33,39], other studies denied the fact that P4P induced behavioral changes at the physician level [30,32,36].

- As for quality, their opinions on the effect of P4P were still controversial (Table 3). Some studies reported that healthcare providers believe P4P will increase the quality of cares [29,30,32,37,40] while others believe that the effect on quality will be a lack of or limited impact [29,33-35,41]. Lastly, regarding financial impact, only one study reported healthcare providers believe there are significant financial impacts [39]. Instead, other healthcare providers thought that financial gains would be limited or minimal [36,41].

- III. Desirable Pay-for-performance Design and Their Concerns

- Table 4 showed healthcare providers' attitudes on desirable P4P design and concerns. In order to summarize providers' opinions, we categorized their points of view into eight general issues such as participation method, evaluation unit and reward recipient, quality indicators, funding, quality of data, additional costs, unintended consequences, and government or health plan's support.

- In relation to participation method, only one study directly mentioned that healthcare providers prefer voluntary participation in P4P program, not mandatory participation [29]. Regarding evaluation unit and reward recipients, some providers preferred individual- (or physician-) based performance evaluation, and therefore financial incentives should be given to physicians who achieved the goal of quality [36]. However, other providers believe financial incentives should provide medical group or healthcare organization based on the result of organizational performance evaluation [29,35].

- Also, many healthcare providers had serious concerns about current quality indicators [29,31-33,36,37]. They believed that current quality indicators did not appropriately reflect on their clinical situations. For example, they believe quality measures cannot be adequately adjusted for patients' medical conditions or socioeconomic status [32]. Therefore they wanted purchasers to work hard to make quality measures accurate and reflect clinical significance [37].

- How to raise funds for financial incentives is another important issue. One article concerned that incentives are not new money so there are always winners and losers [37]. In addition, another study reported that additional funding for P4P should be prepared for financial rewards [29]. That is, healthcare providers prefer to receive additional financial incentives without penalties.

- In order to evaluate quality, healthcare providers should gather correct and accurate quality data and should hand in the data to purchasers. However, they felt that this process is very stressful and they could pay additional costs [29,31,33,37]. Also, for accurate quality evaluation, they believe more data needed, in addition to claims data [29,31,33,37,40]. Therefore, they desired that government or health plans should support the gathering of quality data and should pay for the additional costs or reduce the costs of data collection [29,40].

- Unintended consequences were one of the most vital issues in designing and implementing P4P. Even though one article reported that unintended consequences would not be so serious [30], most healthcare providers had serious concerns that P4P would induce unintended consequences [28,29,31-33,35-37].

- Lastly, the providers felt that they need some support from the government or health plan to make the P4P program more successful. For instance, some articles mentioned that healthcare providers need technical and educational support such as IT infrastructure and electronic medica record [28,30,36,37,40,41].

RESULTS

- Through the results of our systematic review, we determined that healthcare providers have common attitudes regarding several factors of P4P but different attitudes toward P4P programs. Different attitudes seem to show that healthcare providers are under different P4P settings so their main interests could also be diverse. In fact, one study reported that these contextual differences could explain successful implementation of P4P [42] and the context of P4P was considered to be an important factor in other systematic reviews of evaluation of its effect [43]. Therefore, we reported the content as close as possible to the original expressions. At the same time, we could also extract valuable lessons from their common or diverse opinions. We believe that those opinions could give lessons for successful design and implementation of P4P. Following is what purchasers should consider in making a more successful P4P program.

- I. Do Healthcare Providers Correctly Understand What Pay-for-performance Is?

- The purpose of this study was to investigate healthcare providers' attitude toward P4P. To do so, ultimately purchasers can reflect their opinions on designing and implementing P4P programs. Therefore, the basic hypothesis was that they could correctly understand the concept, evaluation method, and the relationship between performance and rewards. However, our results indicated that some healthcare providers still have a low level of awareness about P4P [28-31]. If the low level of awareness or understanding about P4P among healthcare providers is a general phenomenon, that would be a serious barrier to implementing a P4P program. As noted, purchasers should note that the provider's support is essential for the success of P4P [31,32]. Therefore, before implementing P4P programs, purchasers should grasp whether providers are correctly aware of the P4P. If not, they should make an effort to increase the level of awareness such as understanding of the quality indicators and the criteria and methods for distributing financial incentives. This could be a meaningful starting point to reconsider current P4P program. If they have incorrect knowledge about P4P, and if this results in distorted attitudes toward the P4P program, then each P4P program could not get a sufficient degree of support from providers. In order to increase the level of awareness of providers' knowledge and attitudes about P4P, adequate educational support should be provided with them by the health plan or professional societies. Actually, one study reported that providers were more likely to support P4P programs when they had received information about these programs from their professional societies [24].

- II. Why Do They Support or Object to Pay-for-performance?

- Purchasers should pay attention to the reason they oppose P4P. The reasons of opposing P4P may be quite different according to their P4P settings. However, our results showed very interesting phenomenon. That is, two opinions are separated based on different points of attitudes on the same issue. For example, proponents support P4P because it can lead to improve the quality of care and benefits outweigh adverse consequences. On the other hand, opponents disagree on P4P because it cannot lead to improvement in the quality of care and it would result in several unintended consequences. In summary, purchasers should listen to the voices of opponents. If their reasons of objection are correctable or based on misunderstandings, we can reflect their opinions or try to fix them.

- III. Strengthening Communication and Collaboration With Providers in Design and Implementation of Pay-for-performance

- To achieve the final goal of P4P, purchasers should make cooperative relationship and communicate with providers and professional societies. Like Healy and Braithwaite [44] mentioned that "command and control" would be replaced with "the new regulatory state" seeking flexible, participatory, and devolved forms of regulation. From this point of view, purchasers should have patience to persuade providers and facilitate their supportive participation. In particular, in the designing stage of P4P program, purchasers should actively communicate with providers and make an effort to reflect their opinions regarding its primary target, evaluation unit and reward recipients, participation methods, carrots or sticks, and funding methods. Of course, government or health plan cannot and should not accept all opinions from providers. However, P4P is also not a zero-sum game. They may often conflict with each other but can cooperate to make better P4P program.

- IV. Developing Quality Measures Accurate and Reflecting Clinical Significance

- Purchasers should work hard to develop accurate quality measures and reflect clinical significance [37]. According to our study, many healthcare providers had serious concerns about quality measures or indicators. However, there is no perfect evaluation method. Therefore, purchasers should make a continuous effort to monitor and revise current quality indicators regularly in order to reflect providers' professional opinions.

- V. Minimizing the Unintended Consequences

- Purchasers should take actions to minimize the unintended consequences. From the articles reviewed in this study, we could summarize their concerns about unintended consequences [28,29,31-33,35-37]: avoiding high-risk patients; ignoring quality of care; neglecting compulsory services; inappropriate behavioral changes; and threatening professional autonomy. Maybe, each P4P program can confront different kinds of unintended consequences and its solutions would be also quite different. Although these undesirable consequences cannot be eliminated in the real world, some of them can be fixed or minimized by purchasers.

- VI. Are Providers Ready to Implement Pay-for-performance?

- Purchasers should pay attention to whether their providers get ready to launch P4P. Also, purchasers should make a plan to decrease the providers' burdens and supportive environments. According to our results, some providers believe they were not ready to or appropriately prepared to initiate P4P [36] and had concerns about infrastructure for P4P introduction such as IT and the quality of data et al [28,30,31,36,37,40,41]. Technical or financial supports such as providing grants for establishing IT infrastructure, providing education sessions, and sharing costs for additional data collection can be useful strategies for soft-landing of P4P program.

- VII. Study Limitation

- There could be several limitations in this study. One is incompleteness of literature search. Although we used wide range of search terms and references of searched articles, some studies related with this topic might be missed. In addition we did not use comprehensive source of references such as expert's opinion, qualitative studies, secondary data analysis. Second, there is a possibility that providers might intentionally express negative responses to some questions in their survey in order to get a better strategic position in the future P4P. The third limitation is about the heterogeneity of the articles reviewed in the perspectives of healthcare settings, respondents, and questionnaires. As stated, this heterogeneity could be related with healthcare providers' attitudes in each article. Therefore, we intended to describe and summarize the authors' opinions on items by studies rather than provided a single result.

DISCUSSION

- Recently P4P programs have been proliferating across the world, and their main goal was to increase the quality of care by providing financial incentives to healthcare providers. In this study, we reviewed their attitudes toward P4P. Considering their opinions on designing and implementing P4P would be the first step to make more successful P4P programs because they are important stakeholders and key players. Therefore, the purchaser should make more effort such as increasing providers' level of awareness about P4P, providing technical and educational support, reducing their burden of additional data collection, developing a cooperative relationship with providers, developing more accurate quality measures, and minimizing unintended consequences. Since providers' attitudes might depend on the specific context of the P4P program, a survey of the providers' attitudes using items included in this study could be helpful for the soft-landing of a new P4P program.

CONCLUSION

-

The authors have no conflicts of interest with the material presented in this paper.

-

This article is available at http://jpmph.org/.

Notes

- 1. Spitzer AR. Pay for performance in neonatal-perinatal medicine: will the quality of health care improve in the neonatal intensive care unit? A business model for improving outcomes in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Perinatol 2010;37(1):167-177. 20363453ArticlePubMed

- 2. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Value for money in health spending. 2010. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; p. 105-123

- 3. Epstein AM. Paying for performance in the United States and abroad. N Engl J Med 2006;355(4):406-408. 16870921ArticlePubMed

- 4. Dudley RA. Pay-for-performance research: how to learn what clinicians and policy makers need to know. JAMA 2005;294(14):1821-1823. 16219887ArticlePubMed

- 5. Rosenthal MB, Frank RG, Li Z, Epstein AM. Early experience with pay-for-performance: from concept to practice. JAMA 2005;294(14):1788-1793. 16219882ArticlePubMed

- 6. Improving value in heath care: measuring quality. Forum on quality of care. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2010. cited 2011 Jan 21. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/14/27/46098506.pdf

- 7. Pay for performance overview. Integrated Healthcare Association. cited 2011 Mar 23. Available from: http://www.iha.org/pay_performance.html

- 8. Pearson SD, Schneider EC, Kleinman KP, Coltin KL, Singer JA. The impact of pay-for-performance on health care quality in Massachusetts, 2001-2003. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(4):1167-1176. 18607052ArticlePubMed

- 9. Premier hospital quality incentive demonstration project: project findings from year two. Centers for Medicaid Services. 2007. cited 2012 Jan 25. Available from: http://www.premierinc.com/quality-safety/tools-services/p4p/hqi/resources/hqi-whitepaper-year2.pdf

- 10. Medicare physician group practice demonstration fact sheet. Centers for Medicaid Services. 2011. cited 2012 May 25. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/PGP_Fact_Sheet.pdf

- 11. Peckham S. The new general practice contract and reform of primary care in the United Kingdom. Healthc Policy 2007;2(4):34-48. 19305731ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Practice incentive program (PIP). Medicare Australia. cited 2011 Mar 23. Available from: http://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/provider/incentives/pip/index.jsp

- 13. Gilmore AS, Zhao Y, Kang N, Ryskina KL, Legorreta AP, Taira DA, et al. Patient outcomes and evidence-based medicine in a preferred provider organization setting: a six-year evaluation of a physician pay-for-performance program. Health Serv Res 2007;42(6 Pt 1):2140-2159. 17995557ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Armour BS, Friedman C, Pitts MM, Wike J, Alley L, Etchason J. The influence of year-end bonuses on colorectal cancer screening. Am J Manag Care 2004;10(9):617-624. 15515994ArticlePubMed

- 15. Foels T, Hewner S. Integrating pay for performance with educational strategies to improve diabetes care. Popul Health Manag 2009;12(3):121-129. 19534576ArticlePubMed

- 16. Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Sibbald B, Roland M. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med 2009;361(4):368-378. 19625717ArticlePubMed

- 17. Hillman AL, Ripley K, Goldfarb N, Nuamah I, Weiner J, Lusk E. Physician financial incentives and feedback: failure to increase cancer screening in Medicaid managed care. Am J Public Health 1998;88(11):1699-1701. 9807540ArticlePubMedPMC

- 18. Shen Y. Selection incentives in a performance-based contracting system. Health Serv Res 2003;38(2):535-552. 12785560ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Hedgecoe AM. It's money that matters: the financial context of ethical decision-making in modern biomedicine. Sociol Health Illn 2006;28(6):768-784. 17184417ArticlePubMed

- 20. Mansfield RJ. P4P is changing me. Med Econ 2007;84(9):56. 60. 17575889

- 21. Werner RM, Goldman LE, Dudley RA. Comparison of change in quality of care between safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. JAMA 2008;299(18):2180-2187. 18477785ArticlePubMed

- 22. Relman AS. Medical professionalism in a commercialized health care market. JAMA 2007;298(22):2668-2670. 18073363ArticlePubMed

- 23. Dudley RA, Rosenthal MB. Pay for performance: a decision guide for purchasers. Final contract report. 2006. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; p. 1-28

- 24. Murphy KM, Nash DB. Nonprimary care physicians' views on office-based quality incentive and improvement programs. Am J Med Qual 2008;23(6):427-439. 19001100ArticlePubMed

- 25. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. State medicaid director letter. No. 06-003. 2006. 4. 06

- 26. Eichler R, De S. Paying for performance in health: guide to developing the blueprint. 2008. cited 2010 Feb 17. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADN760.pdf

- 27. Oxman AD, Fretheim A. An overview of research on the effects of results-based financing. 2008. cited 2010 Feb 17. Available from: http://hera.helsebiblioteket.no/hera/bitstream/10143/33892/1/NOKCrapport16_2008.pdf

- 28. McDonald R, Roland M. Pay for performance in primary care in England and California: comparison of unintended consequences. Ann Fam Med 2009;7(2):121-127. 19273866ArticlePubMedPMC

- 29. Lee SI, Kim NS, Lee JY, Jo MW, Kim SH, Son WS, et al. Development of pay-for-performance model for quality assessment items in medical care benefit. 2010. Seoul: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; p. 109-139 (Korean)

- 30. Young GJ, Burgess JF Jr, White B. Pioneering pay-for-quality: lessons from the rewarding results demonstrations. Health Care Financ Rev 2007;29(1):59-70. 18624080PubMedPMC

- 31. Erekson EA, Sung VW, Clark MA. Pay-for-performance: a survey of specialty providers in urogynecology. J Reprod Med 2011;56(1-2):3-11. 21366120PubMedPMC

- 32. Casalino LP, Alexander GC, Jin L, Konetzka RT. General internists' views on pay-for-performance and public reporting of quality scores: a national survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(2):492-499. 17339678ArticlePubMed

- 33. Natale JE, Joseph JG, Honomichl RD, Bazanni LG, Kagawa KJ, Marcin JP. Benchmarking, public reporting, and pay-for-performance: a mixed-methods survey of California pediatric intensive care unit medical directors. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2011;12(6):e225-e232. 21057357ArticlePubMed

- 34. Damberg CL, Raube K, Teleki SS, Dela Cruz E. Taking stock of pay-for-performance: a candid assessment from the front lines. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):517-525. 19276011ArticlePubMed

- 35. Pines JM, Hollander JE, Lee H, Everett WW, Uscher-Pines L, Metlay JP. Emergency department operational changes in response to pay-for-performance and antibiotic timing in pneumonia. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14(6):545-548. 17470905ArticlePubMed

- 36. Locke RG, Srinivasan M. Attitudes toward pay-for-performance initiatives among primary care osteopathic physicians in small group practices. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2008;108(1):21-24. 18258697PubMed

- 37. Steiger B. Poll finds physicians very wary of pay-for-performance programs. Physician Exec 2005;31(6):6-11. 16382644

- 38. Reiter KL, Nahra TA, Alexander JA, Wheeler JR. Hospital responses to pay-for-performance incentives. Health Serv Manage Res 2006;19(2):123-134. 16643710ArticlePubMed

- 39. Kaczorowski J, Goldberg O, Mai V. Pay-for-performance incentives for preventive care: views of family physicians before and after participation in a reminder and recall project (P-PROMPT). Can Fam Physician 2011;57(6):690-696. 21673219PubMedPMC

- 40. Goldman LE, Henderson S, Dohan DP, Talavera JA, Dudley RA. Public reporting and pay-for-performance: safety-net hospital executives' concerns and policy suggestions. Inquiry 2007;44(2):137-145. 17850040ArticlePubMed

- 41. Young G, Meterko M, White B, Sautter K, Bokhour B, Baker E, et al. Pay-for-performance in safety net settings: issues, opportunities, and challenges for the future. J Healthc Manag 2010;55(2):132-141. 20402368ArticlePubMed

- 42. McDonald R, White J, Marmor TR. Paying for performance in primary medical care: learning about and learning from "success" and "failure" in England and California. J Health Polit Policy Law 2009;34(5):747-776. 19778931ArticlePubMed

- 43. Van Herck P, De Smedt D, Annemans L, Remmen R, Rosenthal MB, Sermeus W. Systematic review: effects, design choices, and context of pay-for-performance in health care. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10: 247. 20731816ArticlePubMedPMC

- 44. Healy J, Braithwaite J. Designing safer health care through responsive regulation. Med J Aust 2006;184(10 Suppl):S56-S59. 16719738ArticlePubMedPDF

REFERENCES

| Citation | Country | Program | Target | No. of eligible population | No. of study participants | Survey method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pines JM et al., 2007 [35] | USA | CMS & JCAHO | Chairpersons and medical directors from hospitals with emergency medicine training programs in the USA | 129 | 90 | Online questionnaire |

| Locke RG et al., 2008 [36] | USA | Non-specific P4P | Primary care osteopathic physician members of the American Osteopathic Association | 1000 | 123 | Mailed survey |

| McDonald R et al., 2009 [28] | USA & UK | The California initiative & Quality and Outcomes Framework | In the England sample (20) physicians from 2 regions & in the California sample (20) physicians from 4 organizations that ranged in size from 600 to 3,000 physicians and health care clinicians | 20 (UK) & 20 (California) | 20 (UK) & 20 (California) | Face to face interview using the same topic guide |

| Young G et al., 2010 [41] | USA | Managed care plan adopted a P4P program (SNS-A) & P4P for primary care physicians focused on a diabetes care component (SNS-B) | Physicians from CHCs in SNS-A and from medical group in SNS-B | 256 Physicians from 13 CHCs (SNS-A) & 156 physicians from three participating medical groups | 56% (SNS-A) & 63% (SNS-B) | Mailed survey |

| Casalino LP et al., 2007 [32] | USA | Physician P4P program | General internist | 1168 from 1668 randomly selected general internists listed in the AMA physician master-file | 556 | Mailed survey |

| Steiger B, 2005 [37] | USA | Non-specific P4P | ACPE members (physician executives) | 7444 | 932 | Poll |

| Damberg CL, 2009 [34] | USA | Integrated Healthcare Association P4P program | 182 Physician organizations contracted with the seven largest HMOs in California | 35 Physician organizations | 35 Physician organizations: in 14 organizations replaced with similar organizations | Interview |

| Reiter KL et al., 2006 [38] | USA | Statewide hospital- level P4P system between Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and 86 hospitals with which it contracts | 86 Hospitals | 86 Hospitals | 65 Hospitals | Structured interview |

| Goldman LE et al., 2007 [40] | USA | Non-specific P4P | Safety-net hospitals | - | 37 Hospitals | Semi-structured interview |

| Lee SI et al., 2010 [29] | Korea | Non-specific P4P | All healthcare organizations in Korea | All tertiary teaching hospitals, general hospital, and hospital and randomly selected 2000 clinics | 522 Healthcare organizations, including 31 tertiary teaching hospitals, 182 general hospitals, 158 hospitals, and 152 clinics | Web-based survey |

| Young GJ et al., 2007 [30] | USA | Non-specific P4P | The members of physician organizations in Massachusetts and California | - | 1243 physicians: 689 from California and 554 from Massachusetts | Mailed survey |

| Erekson EA et al., 2011 [31] | USA | Non-specific P4P | The members of the American Urogynecologic Society | A total 1203 members of the American Urogynecologic Society | 212 members of the American Urogynecologic Society | Web-based survey |

| Natale JE et al., 2011 [33] | USA | Non-specific P4P | - | Medical directors from all 19 CCS- approved PICUs | 16 CCS-approved PICUs | Postal service and fax transmission |

| Kaczorowski J et al., 2011 [39] | Canada | P4P incentives for preventive care | 246 physicians from 24 primary care network or family health network groups in 110 different sites across southwestern Ontario participated in the P-PROMPT project | - | 115 physicians completed both pre- intervention and postintervention survey | Fax survey |

USA, United States of America; CMS, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services; JCAHO, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; P4P, pay-for-performance; UK, United Kingdom; CHC, community health centers; AMA, American Medical Association; ACPE, American College of Physician Executives; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization; CCS, California Children’s Services; PICU, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit; P-PROMPT, Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools.

| Citation |

General attitudes |

Effects |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | Agree/disagree | Reasons | Behavioral change | Effect on quality of care | Financial impact | |

| Pines JM et al., 2007 [35] | Not mentioned | Disagree on PN-5b | Pn-5b will not lead to improvement in quality of care | Yes | Disagree | Not mentioned |

| Respondents report a number of operational changes that are being implemented to improve time to antibiotics for pneumonia. | Emergency department do not agree that P4P incentives targeting early administration of antibiotics for patients with pneumonia will lead to improvement in quality of care for these patients. | |||||

| Locke RG et al., 2008 [36] | Not mentioned | Skeptical | The majority of survey respondents were skeptical that P4P would appropriately capture the quality of their work and did not believe that health outcomes should influence their reimbursement. | No | Not mentioned | No impact |

| “Attention to meet these performance goals” would not cause significant change in the healthcare of their patients | 72% felt that health outcome measurements should not influence their reimbursement. | |||||

| McDonald R et al., 2009 [28] | Our study found, however, that many physicians were unaware of the target contents or had a poor understanding of the relation between their performance and incentives payments received | UK- Supportive US- Challenging to their autonomy | Not mentioned | UK - P4P changed the nature of the office visit. US - It appeared to have little impact on the nature of the office visit. | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Young G et al., 2010 [41] | Not mentioned | Agree We did not uncover any opposition against P4P | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | P4P may have minimal short-term effect on quality improvement. | No impact on safety net setting |

| Casalino LP et al., 2007 [32] | Not mentioned | Supportive | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | It can lead to increase | Not mentioned |

| Steiger B, 2005 [37] | Not mentioned | Supportive | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | P4P can improve quality | Not mentioned |

| Damberg CL, 2009 [34] | Not mentioned | Agree benefits outweigh adverse consequences | Not mentioned | Yes | Limited | Not mentioned |

| P4P has directly affected organizational behavior by increasing accountability for quality, influencing the speed of IT adoption for quality management, and creating greater organizational focus and support for quality programs and goals | These changes did not translate into the breakthrough improvement in quality desired by plans and purchasers | |||||

| Reiter KL et al., 2006 [38] | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Structure and process changes in organizations | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Goldman LE et al., 2007 [40] | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Improving quality | Not mentioned |

| Lee SI et al., 2010 [29] | Overall low awareness to P4P. Higher level organizations were more aware of P4P than lower level organizations | Disagree except tertiary teaching hospitals | Proponents- It is natural that high performing healthcare organizations receive a financial reward. Opponents- P4P could become a method of government control over healthcare organizations | Positive behavioral change but clinics disagreed | Increased but clinics disagreed | No significant financial effects |

| Young GJ et al., 2007 [30] | Low level of awareness | Agree | Not mentioned | No or minimal change | It can improve quality | Minimal financial impact |

| Erekson EA et al., 2011 [31] | Low level of awareness | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Neutral | Not mentioned |

| Natale JE et al., 2011 [33] | Not mentioned | Mixed agree and disagree | Physicians should be financially rewarded for better patient outcomes. P4P is not an effective way to improve patient outcomes | Agree | Negative | Not mentioned |

| PICU physicians would change their behavior to obtain a financial incentive | ||||||

| Kaczorowski J et al., 2011 [39] | Not mentioned | Agree | Not mentioned | The established target levels and bonuses provided appropriate financial incentive to substantially increase the uptake of mammography and Papanicolaou test | Not mentioned | Positive effect Physicians were given bonus |

| Citation | Desirable design and implementation methods |

Concerns |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical unintended consequences | Other concerns | ||

| Pines JM et al., 2007 [35] | Yes | Yes | Not mentioned |

| 1) Possible solutions are to encourage hospitals to improve overall operations by incentives focusing on the improvement of fundamental measures of patient flow | 1) The provision of antibiotics before chest radiograph results | ||

| 2) provide incentives to hospitals to improve patient safety across all diseases, or | 2) the prioritization of chest radiographs over other radiographs | ||

| 3) provide incentives for process improvement programs. Programs such as these do not focus on specific diseases and may benefit all patients. | 3) and the prioritization of patients with suspected pneumonia. | ||

| Locke RG et al., 2008 [36] | Yes | Yes | They are not ready to implement P4P in terms of technology (IT and EMR). Thus, they need educational support |

| Almost two-thirds of respondents indicated that the insurer should rate them as individuals as opposed to being pooled in their practice group. | 1) These initiatives may focus attention on areas that are not of primary concern during a specific visit between patient and provider-which may cause physicians to miss other important quality goals. | ||

| 2) If a patient presents with a stressful social and medical issue (eg, depression, elder abuse), the physician might spend time addressing issues that could dramatically improve a patient’s life but are not part of measurement guidelines. | |||

| 3) The P4P measures, which will be difficult to implement for many primary care physicians, may also penalize practitioners who treat patients in underserved populations that may not have the resources to follow physician recommendations. | |||

| McDonald R et al., 2009 [28] | 1) This study suggests that the unintended consequences of pay-for-performance programs are likely to vary according to the design and implementation of these programs. Therefore, when designing incentive schemes, more attention needs to be paid to factors likely to produce unintended consequences. | 1) The inability of Californian physicians to exclude individual patients from performance calculations caused frustration. | 1) Threats to the ongoing physician-patient relationship |

| 2) The potential adverse effects of external incentives on motivation are likely to be diminished where individuals identify with the goals and values of incentive programs and feel that they have a degree of autonomy in their delivery. | 2) Some physicians reported such undesirable behaviors as forced disenrollment of noncompliant patients. | 2) US-their autonomy was being challenged | |

| 3) The computerized support required to deliver the targets. | |||

| Young G et al., 2010 [41] | Not mentioned | The survey data did not point to any substantial concerns about unintended consequences. | Safety net providers face complicated and diverse patient needs that compete with P4P’s quality goals for clinicians’ time and energy. One way to mitigate this factor is by improving these providers’ access to information technology. |

| Casalino LP et al., 2007 [32] | 1) Health plans and government will work hard to make quality measures accurate. | 1) Measuring quality may lead physicians to avoid high- risk patients. | Quality measures are not adequately adjusted for patients’ medical conditions or socioeconomic status. |

| 2) Both individual and group evaluation can be possible. | 2) Measuring quality will divert physicians’ attention from important types of care for which quality is not measured. | ||

| Steiger B, 2005 [37] | 1) Additional data needed, in addition to claiming data | 1) Dumping: non-compliant or difficult patients | Physicians spending more time making sure they are meeting certain guidelines rather than treating patients. Some poll participants say P4P is just a convenient way to get physicians and health care organization to adopt better technology. |

| 2) Large organization is now under more favorable conditions in current P4P setting so the rich get richer. | 2) Cherry Picking: they prefer the patients who give them high reimbursement | ||

| 3) More acute indicators and those reflecting clinical significance. | |||

| 4) Incentives are not new money so there are always winners and losers. | |||

| Damberg CL, 2009 [34] | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Reiter KL et al., 2006 [38] | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Goldman LE et al., 2007 [40] | 1) Government should support to gather quality data. | Not mentioned | 1) The cost and accuracy of data collection |

| 2) Government should reduce additional cost resulted from P4P. | 2) The difficulty of getting accurate performance data | ||

| 3) How to adjust case-mix, in particular, underserved patients | |||

| Lee SI et al., 2010 [29] | 1) Voluntary participation | Healthcare providers voiced significant concerns about the potential of unintended consequences including 1)avoiding of high-risk patients, 2) ignoring quality of care in unmeasured areas, 3) neglecting compulsory medical services to maximize financial reward, and 4) the possibility that medical records could be manipulated | Not mentioned |

| 2) The organizational performance should be evaluated | |||

| 3) P4P should reward both high performers and performance improvers with financial incentives, but should not penalize low performers. | |||

| 4) Additional funding should be set aside for financial incentives. | |||

| 5) Not only medical claim data but also other clinical data should be used in evaluation. | |||

| 6) Government or health plans should pay for reporting. | |||

| Young GJ et al., 2007 [30] | Not mentioned | Not serious | A lack of quality improvement infrastructure is a major barrier to achieving pay-for-quality goal |

| Erekson EA et al., 2011 [31] | 1) Performance measures not adjusting for the comorbidity of individual patients | High risk patients will be penalized as they tend to have (worse) outcomes | Not mentioned |

| 2) The need for the development and utilization of appropriate performance measures | |||

| 3) Doubt of adequacy of data | |||

| 4) Careful monitoring of unintended consequences | |||

| 5) Educating physicians about P4P | |||

| Natale JE et al., 2011 [33] | They are wary of the accuracy and validity of data used to generate these performance measures and are discouraged by the time and costs required to collect self information. | Included among these worries that patient data and results can be manipulated by administrators and practitioners, making accurate comparison impossible. One such manipulation is the avoidance of high-risk patients or procedures by physicians. | Not mentioned |

| Kaczorowski J et al., 2011 [39] | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Impact of reimbursement systems on patient care – a systematic review of systematic reviews

Eva Wagenschieber, Dominik Blunck

Health Economics Review.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Pay-for-performance in healthcare provision: the role of discretion in policy implementation in Turkey

Puren Aktas, Jonathan Hammond, Liz Richardson

International Journal of Public Sector Management.2023; 36(6/7): 530. CrossRef - Value-based surgery physician compensation model: Review of the literature

Bethany J. Slater, Amelia T. Collings, Chase Corvin, Jessica J. Kandel

Journal of Pediatric Surgery.2022; 57(9): 118. CrossRef - Incentivizing performance in health care: a rapid review, typology and qualitative study of unintended consequences

Xinyu Li, Jenna M. Evans

BMC Health Services Research.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Guest editorial

Fabiana da Cunha Saddi, Lindsay J L Forbes, Stephen Peckham

Journal of Health Organization and Management.2021; 35(3): 245. CrossRef - Exploring frontliners' knowledge, participation and evaluation in the implementation of a pay-for-performance program (PMAQ) in primary health care in Brazil

Fabiana da Cunha Saddi, Matthew Harris, Fernanda Ramos Parreira, Raquel Abrantes Pêgo, Germano Araujo Coelho, Renata Batista Lozano, Pedro dos Santos Mundim, Stephen Peckham

Journal of Health Organization and Management.2021; 35(3): 327. CrossRef - Awareness of, attitude toward, and willingness to participate in pay for performance programs among family physicians: a cross-sectional study

Chyi-Feng Jan, Meng-Chih Lee, Ching-Ming Chiu, Cheng-Kuo Huang, Shinn-Jang Hwang, Che-Jui Chang, Tai-Yuan Chiu

BMC Family Practice.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Brazilian Payment for Performance (PMAQ) Seen From a Global Health and Public Policy Perspective

Fabiana C. Saddi, Stephen Peckham

Journal of Ambulatory Care Management.2018; 41(1): 25. CrossRef - The impact of pay-for-performance on the quality of care in ophthalmology: Empirical evidence from Germany

T. Herbst, J. Foerster, M. Emmert

Health Policy.2018; 122(6): 667. CrossRef - Hospital-Acquired Infections Under Pay-for-Performance Systems: an Administrative Perspective on Management and Change

Rebecca A. Vokes, Gonzalo Bearman, Gloria J. Bazzoli

Current Infectious Disease Reports.2018;[Epub] CrossRef - Perceptions and evaluations of front-line health workers regarding the Brazilian National Program for Improving Access and Quality to Primary Care (PMAQ): a mixed-method approach

Fabiana da Cunha Saddi, Matthew J. Harris, Germano Araújo Coelho, Raquel Abrantes Pêgo, Fernanda Parreira, Wellida Pereira, Ana Karoline C. Santos, Heloany R. Almeida, Douglas S. Costa

Cadernos de Saúde Pública.2018;[Epub] CrossRef - Physician attitudes toward participating in a financial incentive program for LDL reduction are associated with patient outcomes

Tianyu Liu, David A. Asch, Kevin G. Volpp, Jingsan Zhu, Wenli Wang, Andrea B. Troxel, Aderinola Adejare, Darra D. Finnerty, Karen Hoffer, Judy A. Shea

Healthcare.2017; 5(3): 119. CrossRef - Pay-for-performance reduces healthcare spending and improves quality of care: Analysis of target and non-target obstetrics and gynecology surgeries

Seung Ju Kim, Kyu-Tae Han, Sun Jung Kim, Eun-Cheol Park

International Journal for Quality in Health Care.2017; 29(2): 222. CrossRef - Characterization and effectiveness of pay-for-performance in ophthalmology: a systematic review

Tim Herbst, Martin Emmert

BMC Health Services Research.2017;[Epub] CrossRef - Would German physicians opt for pay-for-performance programs? A willingness-to-accept experiment in a large general practitioners’ sample

Christian Krauth, Sebastian Liersch, Sören Jensen, Volker Eric Amelung

Health Policy.2016; 120(2): 148. CrossRef - Does Pay-For-Performance Program Increase Providers Adherence to Guidelines for Managing Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Taiwan?

Huei-Ju Chen, Nicole Huang, Long-Sheng Chen, Yiing-Jenq Chou, Chung-Pin Li, Chen-Yi Wu, Yu-Chia Chang, Jason Grebely

PLOS ONE.2016; 11(8): e0161002. CrossRef - Pay-for-performance in resource-constrained settings: Lessons learned from Thailand’s Quality and Outcomes Framework

Roongnapa Khampang, Sripen Tantivess, Yot Teerawattananon, Sarocha Chootipongchaivat, Juntana Pattanapesaj, Rukmanee Butchon, Natthida Malathong, Francoise Cluzeau, Rachel Foskett-Tharby, Paramjit Gill

F1000Research.2016; 5: 2700. CrossRef - Pay-for-performance and efficiency in primary oral health care practices in Chile

Marco Cornejo-Ovalle, Romina Brignardello-Petersen, Glòria Pérez

Revista Clínica de Periodoncia, Implantología y Rehabilitación Oral.2015; 8(1): 60. CrossRef - Pagamento por desempenho em sistemas e serviços de saúde: uma revisão das melhores evidências disponíveis

Jorge Otávio Maia Barreto

Ciência & Saúde Coletiva.2015; 20(5): 1497. CrossRef - When incentives work too well: locally implemented pay for performance (P4P) and adverse sanctions towards home birth in Tanzania - a qualitative study

Victor Chimhutu, Ida Lindkvist, Siri Lange

BMC Health Services Research.2014;[Epub] CrossRef - A Qualitative Evaluation of the Performance-based Supplementary Payment System in Turkey

Ganime Esra Yuzden, Julide Yildirim

Journal of Health Management.2014; 16(2): 259. CrossRef - Challenges and a response strategy for the development of nursing in China: a descriptive and quantitative analysis

Yingqiang Wang, Shiyou Wei, Youping Li, Shaolin Deng, Qianqian Luo, Yan Li

Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine.2013; 6(1): 21. CrossRef - The Possibility of Expanding Pay-for-Performance Program as a Provider Payment System

Byongho Tchoe, Suehyung Lee

Health Policy and Management.2013; 23(1): 3. CrossRef

KSPM

KSPM

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite