Factors Associated With Failure of Health System Reform: A Systematic Review and Meta-synthesis

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

The health system reform process is highly political and controversial, and in most cases, it fails to realize its intended goals. This study was conducted to synthesize factors underlying the failure of health system reforms.

Methods

In this systematic review and meta-synthesis, we searched 9 international and regional databases to identify qualitative and mixed-methods studies published up to December 2019. Using thematic synthesis, we analyzed the data. We utilized the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist for quality assessment.

Results

After application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 40 of 1837 articles were included in the content analysis. The identified factors were organized into 7 main themes and 32 sub-themes. The main themes included: (1) reforms initiators’ attitudes and knowledge; (2) weakness of political support; (3) lack of interest group support; (4) insufficient comprehensiveness of the reform; (5) problems related to the implementation of the reform; (6) harmful consequences of reform implementation; and (7) the political, economic, cultural, and social conditions of the society in which the reform takes place.

Conclusions

Health system reform is a deep and extensive process, and shortcomings and weaknesses in each step have overcome health reform attempts in many countries. Awareness of these failure factors and appropriate responses to these issues can help policymakers properly plan and implement future reform programs and achieve the ultimate goals of reform: to improve the quantity and quality of health services and the health of society.

INTRODUCTION

The primary mission of a health system in any country is to promote health and meet the needs of communities regarding public health and diseases [1]. However, given rising external changes, these needs often shift more rapidly than organizations can adapt to considering their complex administrative relations. Reform can be a tool to identify emerging needs, fill gaps, and inject necessary capabilities into a health system so that it can accomplish its primary mission [2]. Growing costs, demographic changes, improved life expectancy and longevity, increased prevalence of chronic diseases, increased literacy/knowledge/awareness, increased patient expectations and needs, and emerging and reemerging diseases all promote escalation in health service consumption, necessitating health reform.

Nevertheless, health system reform requires more than simply improving a health system or healthcare services; rather, it is a sustained, targeted, and fundamental change [1,3–6]. Different countries have different reasons for initiating health reform. In developed countries, health reforms are usually designed in response to exhausted economic growth, aging populations and growing health-related expectations, and rising medical technology costs. In contrast, developing countries most frequently design reforms to expand the coverage of essential services to disadvantaged populations, improve service quality, distribute resources equitably, and coordinate services across various levels [3,4].

The experiences of different countries reveal that health system reform is highly political and contentious [1] and, in many cases, has not achieved the expected goals. The first problem faced by reform is responding to basic health needs, which often do not directly translate to financial demand, due in large part to poverty [6]. Therefore, policy implementation carries a risk of exacerbating inequality. Moreover, the pressure to implement prompt reforms in times of crisis to rapidly progress and repair damage may do little to improve existing inefficient or inequitable systems [7].

In general, the main goal of any health system reform is to understand and address new and changing needs and expectations in the field of health. However, reforms in most countries fail due to deficiencies in political leadership and long-term commitment to the reform program, hasty initiation, unscientific reform planning, over-reliance on modeling from separate developed countries, use of traditional change strategies, and resistance from authorities [5,6].

Several countries have begun the reform process, including Great Britain (in the United Kingdom) in 1989 to increase productivity by promoting competition, Canada to control costs, Chile in 1973 to improve the position of the private sector, and New Zealand in 1991 to improve the efficiency of the health system to reduce waiting time. In some cases, they achieved relatively satisfactory results; however, other cases showed that due to poor implementation, the reform increased discontent. Countries encountered new issues even after successful reforms, requiring a repetition of the reform cycle [7–9]. Despite the importance of this issue, existing studies on the reasons for reform failure have been conducted case-by-case, and a clear-cut analysis is required of the reasons for the failure of health reforms. In the present analysis, we collected relevant studies, analyzed their findings, and thoroughly interpreted the reasons for reform failure in order to build a more comprehensive and integrated understanding of this phenomenon.

METHODS

Aim

Studies exploring the failure of health sector reform around the world, both in developed and developing countries, were systematically reviewed, critically appraised, and thematically analyzed to gain a collective understanding of the factors associated with the failure of health sector reform.

Review Approach, Search Strategy, and Inclusion Criteria

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to identify, screen, and select the relevant studies. We used established guidelines for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews [10] and the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research statement [10] for data extraction, integration, analysis, and reporting of the study results. We systematically searched several international databases, including Web of Science (ISI), PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Embase, CINAHL, and MEDLINE, as well as regional databases, such as the Scientific Information Database, Magiran, and Iranmedex, up to December 2019. Because the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 disrupted the normal conditions of health systems and policies, we chose to exclude post-epidemic studies from this review. We limited the languages to English and Persian, but our search strategy had no other limitation, such as in subpopulation. The initial search strategy was selected using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) subject headings and keywords of related papers in MEDLINE. The following keywords were used to search: (“Health” OR “health system,” OR “health care”), (“Reform” OR “Evolution” OR “Change” OR “Revolution” OR “Transformation”), (“Unsuccessful” OR “Failure” OR “defeat” OR “Failed”), (“Qualitative Research and Exploratory”). To increase the sensitivity and broaden the scope of the search strategy, complementary searches were conducted based on the reference sections of relevant review studies, books, and critical journals relating to the failure of health system reform. We used the EndNote X7 citation manager (Clarivate, London, UK) to screen and manage the papers during the online search of several databases.

Study Selection

All studies assessing the factors associated with health system reform failure and health system policies in various countries were enrolled if they met the eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria used to select relevant studies were (1) examination of reasons for the failure of health reforms generally and comprehensively and (2) publication by the end of 2019 in English or Persian. Studies that examined a single country-specific reform policy or the reform of a specific component of the health system were excluded.

To screen the articles, 2 researchers (MK and RK) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts to decrease the bias associated with exclusion of irrelevant articles. If a disagreement arose between the researchers in the exclusion process, reconciliation checks between the 2 researchers and consultation with the third coauthor (MB) were used to reach a final decision. In the full-text review stage, all articles included in the title and abstract review were assessed independently by 2 reviewers (MK and RK), and papers were included if they met the inclusion criteria.

Quality Assessment

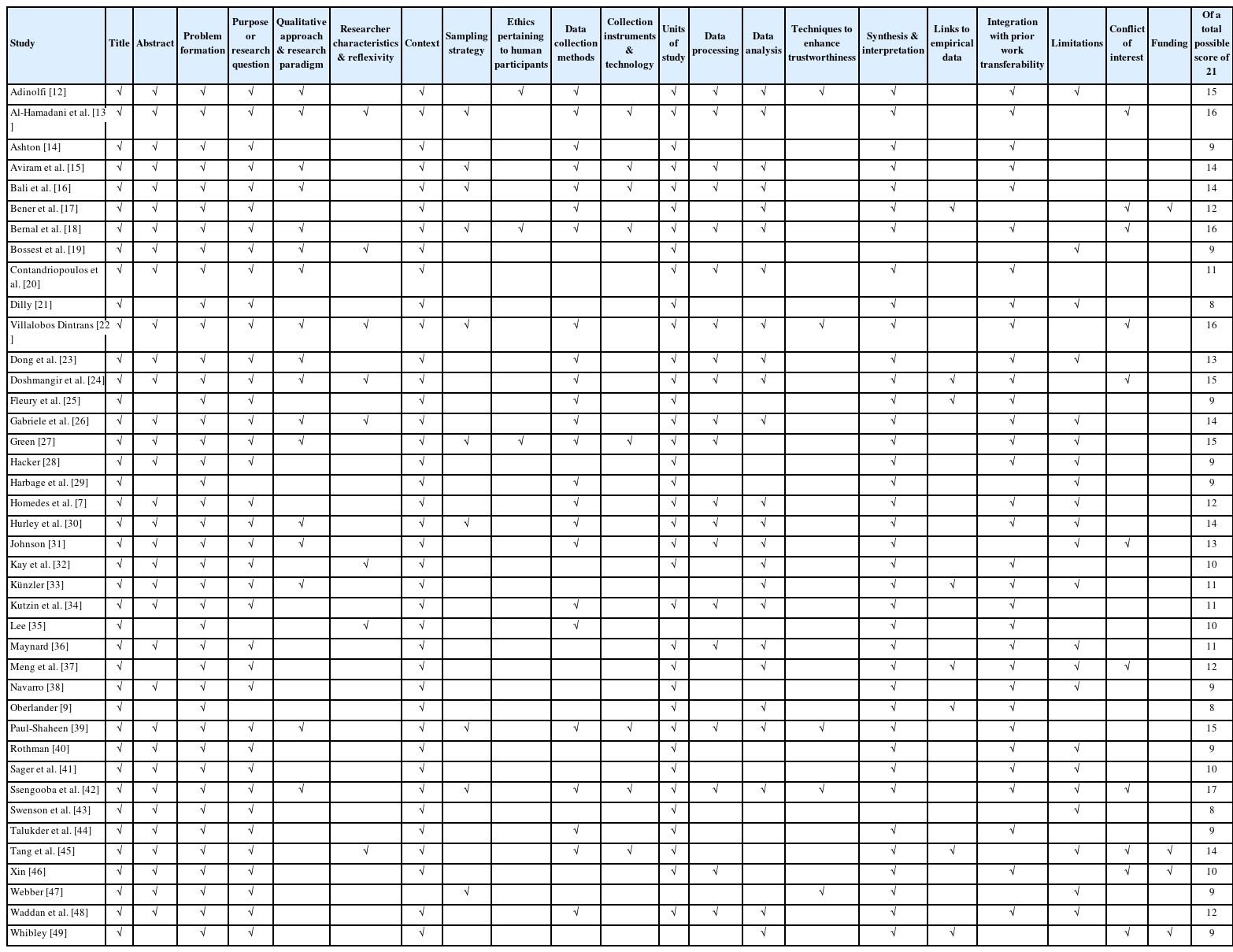

We used the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist to assess the quality of the included studies [11]. The SRQR questionnaire includes 21 questions that cover various scientific and methodological aspects. The lowest and highest scores of the SRQR were 0 and 21, respectively. Articles with less than 40% of the highest SRQR score were considered low quality and excluded, while those with levels of 40–70% and more than 70% were considered to be of middle and high quality, respectively. Table 1 [7,9,12–49] shows the results of the quality assessment of selected articles.

Data Synthesis

After study selection, for data analysis and synthesis, we used the thematic synthesis approach developed by Thomas and Harden [50]. Based on this model, we synthesized the results as follows. First, 2 author’s extracted free codes by independently reviewing studies line by line. All free codes were extracted based on the research aims and regardless of their direct or indirect relationship to the failure factors of health reforms. Then, the initial free codes of the findings were organized and summarized via descriptive coding, forming sub-themes. Finally, sub-themes were interpreted as so-called analytical themes, which were third-order interpretations.

Validity, Reliability, and Generalization

Without generalization, research cannot be used as evidence by other researchers and policymakers (our main target group). To ensure the generalizability of the study, we observed 3 indicators. The first measure was the validity of the study, which we ensured by fully and transparently following the steps of the appropriate PRISMA tool. We used Silverman’s 5 approaches to increase the reliability of the process and results. That is, the article texts were read line by line, results obtained by 2 people were continuously compared, deviant cases were discussed, and illustrative tables were used to represent the data.

For generalizability, we promoted analytical generalization by involving researchers with several years of experience in the field of health and health reform to judge which studies to include in the systematic review as well as the final analytic codes. These researchers could properly judge generalizability of the included studies based on similarities in time, place, people, and other social contexts of reforms across countries and exclude fundamentally different studies. After the initial list of key concepts was established, the relationships between these concepts were determined through several group discussions; thus, the overall themes and sub-themes were identified.

Ethics Statement

The ethical committee of the Center approved this study for Health Human Resource Research and Studies of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education in Iran.

RESULTS

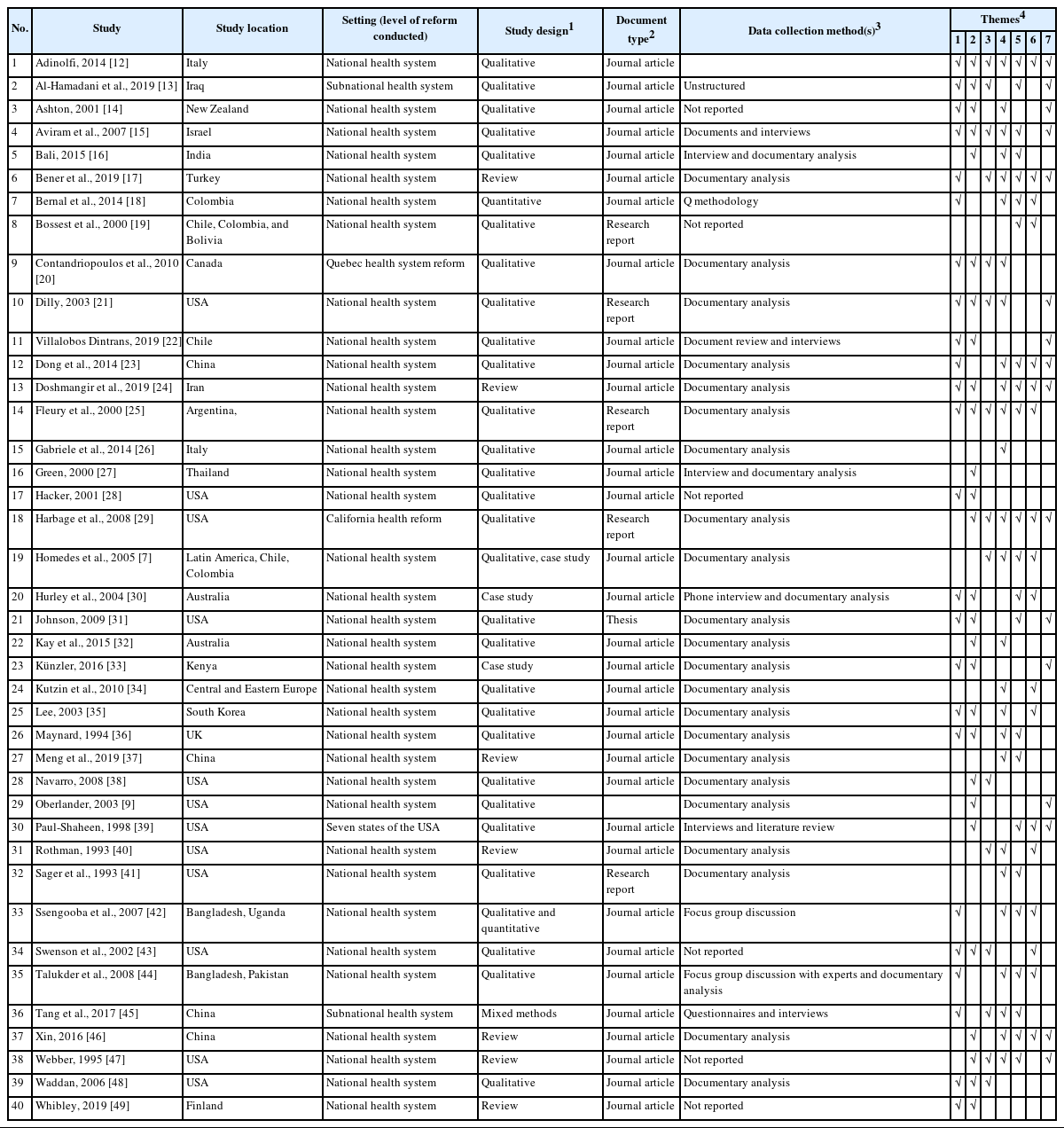

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this study and based on the PRISMA guidelines, of 1837 articles, 1359 were excluded due to duplication and 367 due to irrelevance of the title, abstract, or type of research (Figure 1). After assessing 111 full-text articles for eligibility, we excluded 10 because of a lack of focus on health system reform, 34 due to insufficient data for analysis, and 27 for examining a single policy or reform non-generally. Finally, we selected 40 articles [7,9,12–49] for content analysis and data extraction about the factors affecting reform failure. The characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart of search and screening process.

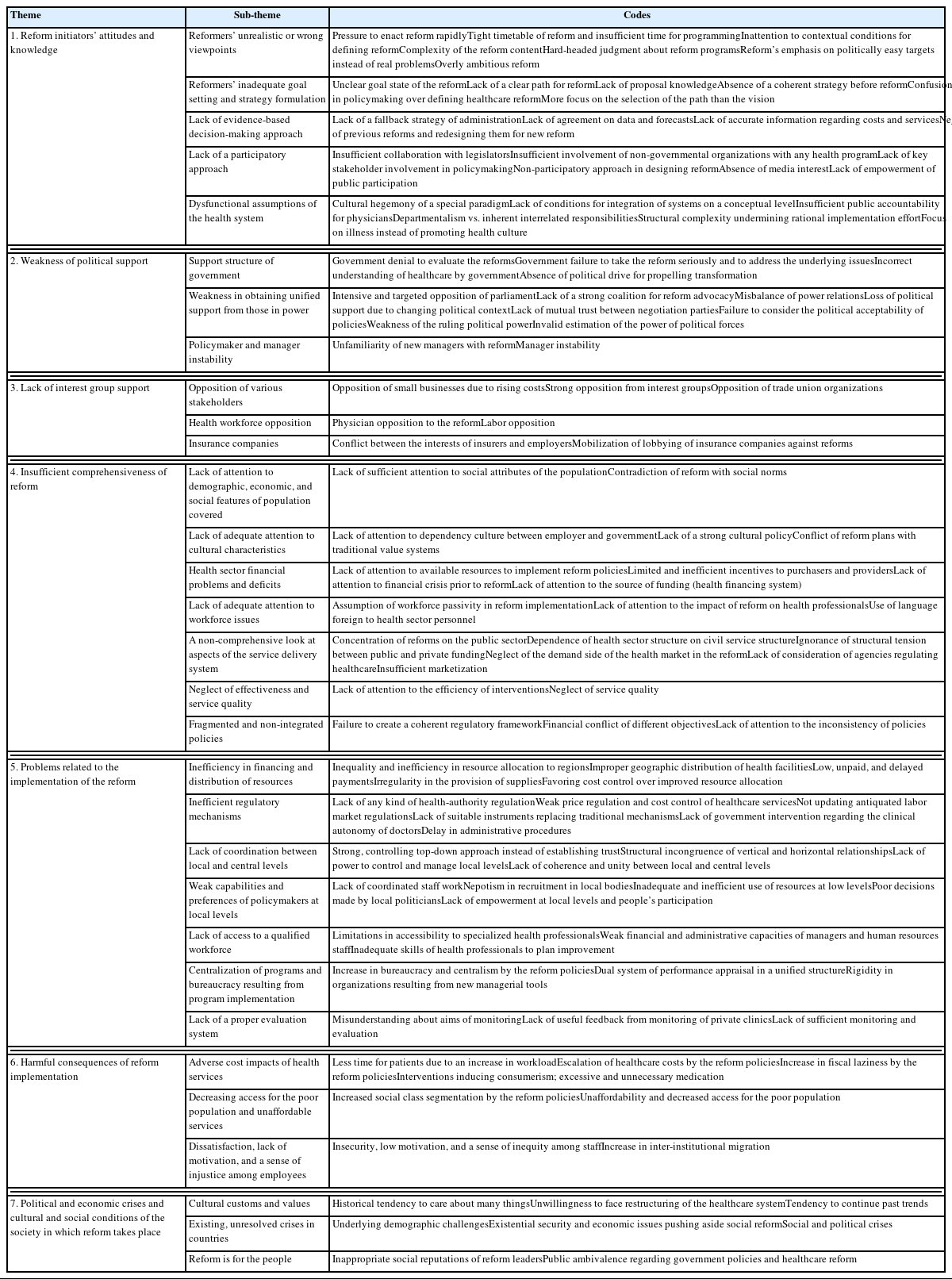

The authors discussed factors influencing the failure of health system reforms in 7 main categories and 32 subcategories extracted through content analysis of the articles (Table 3). The categories are as follows.

Reform Initiators’ Attitudes and Knowledge

Twenty-four studies discussed the reforms initiators’ attitudes and knowledge as leading to the failure of health reform. This category is organized into 5 subcategories.

Reformers’ unrealistic or wrong viewpoints

May cause reform failure. Reformers’ emphasis on politically easy targets [20,22], lack of belief in fundamental/structural changes [18], overly ambitious goals [48], differing explanations for problems [23], and hard-headed judgments about reform programs [43] contributed to reform failure [17,33]. Entire social and healthcare ecosystems must be simplified for any single expert or politician to understand them. Lack of sufficient attention to contextual conditions when designing the reform [42], designing or implementing it hastily or (vice versa) over a very long period [30,31,36], or inaction under the pressure of government or parliament [14,39] have produced inconsistent outcomes. Complexities in the health system complicate thinking about structural reform. Time limitations challenge governments by assigning a short life to a process that requires maturation [22]. A defined philosophy, a transparent and ethical approach to the health system, and an overall plan to navigate various policy interventions and reforms toward a suitable healthcare model are needed [24].

Reformers’ inadequate goal setting and strategy formulation can involve imagining an unclear goal state or an indistinct path for reform implementation. Poor priority setting and focusing more on the path than the vision (such as health improvement and equity) were factors here [14,17,28,30,33,36,47].

Another sub-theme is the lack of an evidence-based decision-making approach. Reforms planned without accurate information (especially regarding expected increases in costs and services), lacking agreement on the data and related forecasts [12,15,17], and without a fallback strategy for administration [9] have been unsuccessful.

Another highlight that should be taken into consideration accurately before creating reforms is the dysfunctional assumptions of the health system [45]. When the main orientation of a medical system is towards individuals and not society, we are often limited to medical issues and rarely challenge whether the medical model is worthy of the enormous societal investment or not. Moreover, the focus of reforms would be on illness rather than promoting a health culture, and weak support for preventive programs [20,24,47].

Finally, some policymakers lacked a participatory approach or ignored the roles of key stakeholders such as physicians and administrators, legislative authorities, the media [31], non-governmental organizations [33], insurance company representatives [21], and patients [12]. Improvement is needed in designing or implementing reforms [12,15,21,25,30,44].

Weakness of Political Support

Twenty-six studies discussed the weakness of political support as potentially initiating the failure of health reform. This category, organized into 3 subcategories, is among the most challenging [30].

The support structure of government is highly critical. Failure results when the government does not take the reform seriously [15,28], lacks proper knowledge and understanding of it (or health as a whole) [35,46,49], and/or avoids using a rights-based argument to justify its health policy [33] and evaluate the reforms [36]. The need for increased stewardship over the health system [16] and a lack of political drive for propelling transformation in a highly centralized political process [25] complicate the implementation of healthcare reform.

Weakness in obtaining unified support from those in power [21,27,28,31,36,39]: Firm political support and policymaker commitment are essential for reform [24]. Failure is facilitated by weakness of the ruling political power or poor integration and coordination between different parts of a country’s government and, consequently, its health sector [29,47]. The imbalance of power relations [29] or political fragmentation in the government body and lack of mutual trust between negotiating parties create difficulties in ratifying and implementing fundamental health reforms [15].

Policymaker and manager instability is a global issue, and the financial pressures on healthcare and social care have never been more meaningful [49]. Frequent changes in the environment, political circumstances and management instability, and unfamiliarity of new managers with reform are inherent to this category [12–14,30,32].

Lack of Interest Group Support

Fourteen studies discussed a lack of interest group support as contributing to the failure of health reform. Three factors, relating to the variety of interest group viewpoints and the process of obtaining their support, make up this category.

The opposition of various stakeholders such as individual executives (due to rising costs) as well as barriers between health ministries or departments [17] and academic institutions, trade union organizations, or other interest groups plays a role [29,38,43,47].

Health workforce opposition: The levels of cooperation between organizations and professionals are usually low [45]. Physicians are one of the primary beneficiaries, and their resistance can directly challenge the reforms [12,20]. Physicians’ attitudes [15] and their connection to medicine’s financial aspect [13] can lead to their resistance to change. If a manager tries to impose discipline, healthcare staff may leave the institution [13]. Other health workers’ attitudes and relevant associations are also fundamental [15,25,40].

Insurance companies are another strong interest group. Their lobbying against reform and conflict between their interests and those of employers reduce the chance of success [21,29,38].

Insufficient Comprehensiveness of Reform

Twenty-six studies discussed insufficient reform comprehensiveness as affecting the failure of health reform. This category, organized into 7 sub-themes, indicates that reforms that do not account for various dimensions and that lack essential comprehensiveness fail in practice.

Lack of attention to demographic, economic, and social features of the population covered: If the reform cannot create harmony between different strata (poor, middle class, etc.) or sacrifices the middle class in the delivery of public services [25], it will not succeed. The failure to accurately identify or estimate the target population for insurance also causes issues [24,37,47]. Finally, the conflict of reform with social norms, as well as noncompliance with social and political movements, may cause problems [12].

Lack of adequate attention to cultural characteristics: Offering a robust cultural policy synchronized with traditional value systems is helpful [14]. Lack of attention to dependency culture between employers and the government and affiliation with social security, especially for people in the lowest income bracket, have sometimes been noted in reports of reform failure [7].

Health sector financial problems and deficits: Lack of careful attention to the existing financial situation of the health system and financial resources can generate serious challenges to any action in the health sector [7,15,16,18,21,24–26,29,34–36,41,42,47]. Historical budgets need space for significant reorganization [20], and healthcare funding should be reinvented entirely [21]. Unsustainable financing, overutilization, and delayed payments to service providers have endangered reforms [24]. In this arena, health insurance costs are high [18, 21,44].

Lack of adequate attention to workforce issues, such as human resources for health behavior, motivations, or character, and failure to consider the impact of reform on health professionals is an essential factor [10,18,21,35,40,42,45]. It is misguided to assume that the workforce will act passively in the reform [42] or to use unfamiliar language [14]; these trigger opposition or resistance of the workforce.

A non-comprehensive look at aspects of the service delivery system: Concentration on the public and neglect of the private sector [16], use of an inadequate multidisciplinary approach [17], failure to acknowledge system members as autonomous agents with independent purposes and adaptable abilities [45], ignorance of structural tension between public and private funding [32], and development of an improper marketization spectrum that is either excessive or insufficient [23] are longstanding contributors to health policy failures [24].

Neglect of effectiveness and service quality: An absolute focus on cost control, along with the failure to develop a mechanism for quality control of services, also leads to reform failure and can prevent reform from reducing inequality after policy implementation [25]. Evidence regarding successes, such as clinical trials and economic evaluations, is essential to indicate which treatments are cost-effective [36].

Fragmented and non-integrated policies: Policy alignment and coordination (both financial and non-financial) is vital [12,14,44]. A strong fragmentation of the policy field hinders attempts to create agreement among the various stakeholders [26]. So-called social responsibility and success and efficiency on par with businesses outside the area of reform are both admirable, but they potentially conflict with structural complexity, impacting policy diversity and potentially undermining rational calculation and implementation efforts [23].

Problems Related to the Implementation of the Reform

Twenty-three studies indicated that regardless of the political situation and the content of the reform, some factors in the implementation phase create grounds for failure. This category is organized into 7 subcategories:

Inefficiency in financing and distribution of resources: Inequalities in resource allocation across regions or improper geographic distribution of health facilities are the most noteworthy problems in this category [13,17]. Other causes include excessive attention to wealthier areas [8] or the prevention of regional transfer of medical insurance policies based on regional economic and social conditions [23]. Health needs are greater among rural residents than city dwellers, but those residents need the power to lobby and negotiate to receive more resources [7], especially in reform policies pursuing decentralization.

The inefficiency of the distribution of financial resources in many reforms has manifested in low payments to healthcare providers or frequent delays in payments and benefits provided. Low salaries and delayed payments have had consequences, such as members of the health workforce’s choice to simultaneously work in the private sector to compensate for costs [42].

Inefficient regulatory mechanisms have manifested in various forms and have negatively affected the implementation of health reforms. This occurs when the reform process is not subject to any health-authority regulations [25] or when limited effective mechanisms exist to replace traditional regulatory mechanisms, such as bureaucracy and over-control via corporate self-regulation or health market regulations [25,36].

Another area of law and regulation is the development of economic regulations, including control of costs, targeted control of spending in the private sector to prevent spending shifts to the public sector, and other examples [7,47]. More than cost control, a need exists for pricing and counter-productive policies that appropriately set profit and price margins for services in both private and public sectors [36,46]. Delays in the development of administrative procedures have sometimes led to the loss of opportunities, such as obtaining the required budget [29].

The lack of coordination between local and central levels is another problem. Crucial factors behind this inconsistency include a robust and controlling top-down approach instead of establishment of trust, structural incongruence of vertical and horizontal relationships, a lack of power to manage local levels, and a lack of coherence and unity between local and central levels [12,23,30,45].

Lack of coordination has led to structural challenges when primary levels must implement and pursue multiple goals at many local levels in different geographical areas and with different capacities [23]. This can also happen horizontally, since a broad set of actors and organizations, with different roles and interests, are involved in the reform. This problem becomes much more prominent when the ministerial structure is fragmented [16,23,37,42]. Central levels, as essential actors, may aid in reform implementation if they speak with a strong voice and constantly grapple with inconsistencies and tensions of policies and reform [23,31].

Weak capabilities and preferences of policymakers at the local level: At local levels, a lack of power to coordinate staff work [15], the allowance of individual tendencies and preferences in the implementation of reform programs [42], the inability of local politicians and communities to make correct health decisions or follow technical recommendations [7], and a lack of power at local levels to empower the public lobby and people’s participation [15,25,29] challenge the implementation of reform programs.

Lack of access to a qualified workforce: The best implementation policies require suitable executives. Often, however, a dysfunctional employment system has predominated [13]. Thus, more human resources, experts, and technical resources are required [16,18,25]; alternatively, the existing workforce must have sufficient proficiency and required skills, or a proper plan must exist to improve workforce knowledge about reform issues [17,37]. These human resource improvement areas can hamper implementation and create deviations in implementing goals [7,12,18,42,44]. Among the most important of these skill shortages, the weak financial and administrative capacities of managers and human resources staff have affected the sector’s performance, especially when reform has transferred some responsibilities to local levels [16,31,36,44].

Centralization of programs and bureaucracy resulting from program implementation: These bureaucracies create obstacles in accessing administrative services at the management level, such as delays in payments or impacted professional autonomy [7,12,42]. One bureaucratic problem associated with reform is the creation of dual lines of technical and administrative control in a unified structure, which causes stakeholder dissatisfaction due to duality and can double the time required to meet supervisors’ expectations [42].

Lack of a proper evaluation system: At the time of implementation, reformers must determine whether the reform is aligning with its stated and unstated goals. In some unsuccessful reforms, a need existed for more monitoring of aims and helpful feedback obtained by monitoring private clinic [7].

Harmful Consequences of Reform Implementation

Adverse consequences of health reform programs have been a primary reason for the failure of these programs. Across all stages, including design, development, and implementation, some reforms have had negative results that have affected stakeholders and the provision of health services. Eighteen studies discussed these negative consequences. This category was organized into 3 subcategories.

Adverse cost impacts of health services: Reform policies such as expensive hospital-based and specialized healthcare services; irrational use of medicines, medical equipment and paramedical services; and the fee-for-service payment method or reliance of workers such as doctors on the sale of drugs and technologies for income have inflated employer health costs and triggered an explosion in pharmaceutical and equipment costs [7,24,35,43,46,47]. The need for coordinated and integrated care, along with a dysfunctional referral system, has resulted in the overutilization of healthcare services, most of which were reimbursed by the insurance funds but were challenging to afford [24]. A major factor adversely impacting the cost of healthcare was the funding mechanism of reducing the cooperative expenditures and physician workloads with little public monitoring and regulation of healthcare services provided by doctors and pharmacists [7,12,24,34,35,40,46].

Decreased access for the poor population and unaffordable services: Despite efforts to provide and distribute resources fairly, problems with access to services have not necessarily been rectified, and service coverage has not become more equitable [17]. This has occurred due to a focus on specific financing processes or increasing the role of the private sector, high-deductible insurance policies focused on hospital and curative services instead of preventive care, increased differences between urban and rural areas, and social class disparities [7,23]. Publicly insured patients often wait excessively long. In many countries, health insurance coverage rates remain low, primarily due to unaffordability and a lack of health insurance infrastructure [7,17,25,29,39,44].

Dissatisfaction, lack of motivation, and a sense of injustice among employees [42] have led to more consequences, such as increased inter-institutional migration in various forms [7,25]. Poor economic status and unclear rights and responsibilities among government employees [13] are consequences of lack of attention to the working conditions of employees [18], increased workload and job stress [7], lack of adequate income guarantee and job security, aggravated or unresolved promotional and career structure problems preceding reform [42], fear of the unknown and concern [30], sense of being caught in the middle of the financial shortcomings of government, and high expectations created by reform promises [42].

Political and Economic Crises and Cultural and Social Conditions of the Society in Which Reform Takes Place

A review of various worldwide reforms (16 studies) shows that even well-designed and well-implemented reforms, with full political and financial support, have yet to be successful in some cases.

Reforms are hindered by certain cultural customs and values, including a lack of general awareness [17]; a historical tendency to care about many things; problems of coordination, control, and implementation [13,23]; general unwillingness to face very complex trade-offs [47]; and tendency to continue past trends [12,13,47].

Existing, unresolved crises in countries: These include underlying demographic challenges such as lacking a window of opportunity [33], a high number of uninsured people in the country, or a high percentage of illegal and legal immigrants [29]. Existential security and economic or social and political issues that have occupied the people’s and politicians’ immediate attention and time [13,15], such as unfair international sanctions against Iran and their likely adverse effects on health indicators and access to healthcare services [24].

A widespread sense that reform is for the people has made the foundations of reforms slippery and unstable. Mistrust between the people and the government, public ambivalence regarding government policies and healthcare reform, and inappropriate social reputations of reform leaders have made it difficult to obtain substantial support from the public. Additionally, people may be satisfied with their healthcare arrangements, and reforms threaten to unsettle them [9,13,14,21,22, 31,39,46,47].

More generally, each of the 7 main factors can be placed either before, during, or after the reforms. The possible responses of the health system to each factor, depending on its placement on the spectrum, can stimulate the failure of health system reform. Regarding the importance of the stages to reform failure, all of the abovementioned factors that fall in the pre-implementation phase and even before the formulation of reforms will have the greatest impact in guiding the reforms in the right direction. As such, the 2 factors of the reform initiators’ attitudes and knowledge and the weakness of political support have been considered by the researchers of the reforms in selected studies. This was done by attracting support for implementation and selecting competent reformers to choose appropriate strategies for the formulation and the comprehensiveness and extent of reforms.

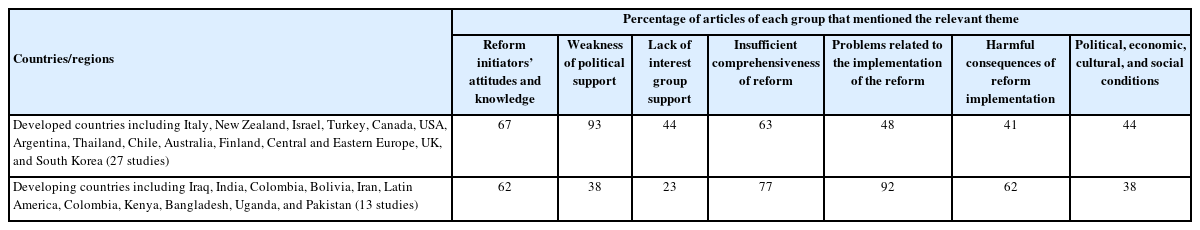

Comparing the Factors of Reform Failure Between Developed and Developing Countries

According to the purpose and results of the study, the factors that can lead to the failure of health system reforms in developed and developing countries were placed in 5 general categories as the most key and influential factors. First, these factors help to understand the great complexity of the health system. However, in an applied sense, it is also possible to increase the probability of success of health system reforms by examining each of these factors and understanding how to deal with them according to a country’s level of development.

As shown in Table 4, it can be concluded that factors such as the knowledge and attitudes of the main designers of the reform and the comprehensiveness of the content of the reform, as well as financial and political issues, are similar failure factors of health reforms in both developing and developed countries. However, the lack of political support and the lack of support of interest groups has been more important in developed countries, which is meaningful considering the existence of strong and structured political parties as well as trade unions in these countries. Problems with reform implementation have been more important in developing countries, which is a function of lacking strong management in the implementation of even well-formulated programs.

DISCUSSION

We conducted this review to identify factors influencing the failure of health system reforms. To this end, we systematically reviewed 40 articles that met the inclusion criteria. By reviewing the experiences of various countries using a thematic synthesis approach, we found that the failure of health system reforms is affected by 7 factors. A substantial contributor to reform failure stems from the policymaking process and the political environment in which reforms are designed and approved. Governmental support and power relations were discussed in most studies [15,33,35,46,47]. In most countries, the political parties that impact governments and parliaments have different policies and strategies; the resultant political fragmentation and conflicts of interest among parties challenge health reforms [9,43,47]. Factors relating to the political context were common in developed and developing countries. In a study by Cassel et al. [1], the first factor in the success of reform was the political nature of the reform process and the importance of political leadership. The failure of the Clinton health plan is an excellent example of policy process failure [31].

Other factors stem from the nature and content of the reform. The comprehensiveness of the reform involves various aspects of efficiency and effectiveness. We found that factors in reform failure include contradictory policies and strategies, the absence of an objective understanding of the present situation and failure to assess existing capacities of health systems, and the disconnect of reform policies from the mission and main objectives of health reforms [1,7,10,27], where these objectives include health improvement, equity, and patient satisfaction [1,45]. These findings align with the World Health Organization’s consideration of reform as a dynamic and political process and emphasis that reforms must take place as sustained processes of fundamental change in the context of health policy and health institutional arrangements [51].

That said, a good plan does not guarantee success; some factors relate to the implementation of reform. Implementation of health sector reforms resembles any other policy in that it requires evaluation and revision to produce the expected outcomes. Effective tactics include coordination between levels, administrative procedures, resource allocation for sustained implementation of the reform, and monitoring and evaluating systems used in other cases [13,17,24,29]. Some occupational groups such as physicians, health workers, insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and others may oppose changes or exhibit defensive behaviors because they feel that the reform would threaten their positions in the medical/health status quo [15,20,40]. Lack of adequate attention to the fundamental issue of human resources and the lack of development of appropriate strategies leads to the failure of reforms [14,27, 52]. This is particularly relevant to the case of Quebec, in which analysis shows that the obstacles to health reforms may relate less to what to do than to how it is done [20]. In support of this notion, one reason for the success of reforms in Turkey immediately after policy development and decision-making was the establishment of written guidelines and standard operating procedures [17].

This review showed that sometimes unexpected consequences of reforms, such as reduced service accessibility or reduced cost benefits, contribute to failure [7,29,30]. A reform initiative in China, in which county hospital efficiency was not meaningfully improved [53], and the impending risk of market failure due to the massive privatization of the health sector in Georgia [54] support the results of our study. The political, economic, social, and cultural contexts in which the reform takes place may influence all other factors. Our review indicated that economic crises or constant environmental and political changes could be fundamental issues. These factors imply diverse experiences across settings [14,17,21,46].

As previously described, in the present study, we examined the health reform experience in multiple countries. Despite limitations of access to a limited number of studies and their analysis, we conclude that all health systems, in both developing and developed countries, have faced many obstacles and challenges in establishing and implementing health reforms. We have covered an extensive selection of these factors in our study. Each of these issues is a potential reason for problems with or even failure of health reforms. Therefore, noting the importance of reforms to a country’s health system and the enormous expenditures on this process, these factors should be considered and evaluated for all stages of reform. Our study is the first systematic review examining factors contributing to failure of countries’ health system reforms. Methodologically, in this study, we searched all valid databases, carefully appraised article quality, and evaluated all selected articles to provide a coherent body of evidence.

Limitations

In our study, we used a qualitative evidence synthesis approach, which can provide valuable evidence to improve our understanding of reform complexity, contextual variations, implementation, and country preferences. However, the synthesis of qualitative studies involves challenges, including how to include studies from a great diversity of countries and cultures, as well as the challenges of reducing, merging, and abstracting the findings of primary studies without losing meaning. By following the thematic analysis steps described in the methodology section, we were able to merge data while retaining meaning. Nevertheless, limited knowledge of other languages and the choice to include only English-language or Persian-language studies are likely to exclude some knowledge conveyed in other languages. Additionally, despite the selection of a sophisticated search strategy and the search of many databases, a knowledge gap may exist in this area due to the high volume of gray literature in the field and unpublished organizational reports, particularly in developing and underdeveloped countries.

CONCLUSION

Analyses of the studies included in this review will allow policymakers, policy analysts, technical teams, and researchers to develop practical approaches to improve health system reform design and implementation. We found evidence that interventions meet health reform objectives when they are targeted and carefully designed. Health system reform is a deep and extensive process in which shortcomings and weaknesses in each step have overcome health reform attempts in many countries. Awareness of these failure factors and appropriate responses to these issues can help policymakers properly plan and implement future reform programs and achieve the ultimate goals of reform: to improve the quantity and quality of health services and the health of society.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All the data analyzed and reported in this paper were from published literature, which is already in the public domain.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Khalilnezhad R, Bayat M. Data curation: Fattahi H, Khodadost M, Ghasemi Seproo F, Shokri A. Formal analysis: Fattahi H, Khodadost M, Ghasemi Seproo F, Shokri A. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: Khalilnezhad R, Khodadost M, Bayat M. Project administration: Bayat M. Visualization: Ghasemi Seproo F, Younesi F. Writing – original draft: Ghasemi Seproo F, Younesi F, Khalilnezhad R. Writing – review & editing: Bayat M, Kashkalani T, Khalilnezhad R, Fattahi H, Khodadost M, Ghasemi Seproo F, Shokri A, Younesi F.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Center for Health Human Resource Research and Studies (CHHRRS) of the the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) in Iran supported this study.