Regional Differences in the Effects of Social Relations on Depression Among Korean Elderly and the Moderating Effect of Living Alone

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

Socioeconomic disadvantages interact with numerous factors which affect geriatric mental health. One of the main factors is the social relations of the elderly. The elderly have different experiences and meanings in their social lives depending on their socio-cultural environment. In this study, we compared the effects of social relations on depression among the elderly according to their living arrangement (living alone or living with others) and residential area.

Methods

We defined social relations as “meetings with neighbors” (MN). We then analyzed the impact of MN on depression using data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging Panel with the generalized estimating equation model. We also examined the moderating effect of living alone and performed subgroup analysis by dividing the sample according to which area they lived in.

Results

MN was associated with a reduced risk of depressive symptoms among elderlies. The size of the effect was larger in rural areas than in large cities. However, elderly those who lived alone in rural areas had a smaller protective impact of MN on depression, comparing to those who lived with others. The moderating effect of living alone was significant only in rural areas.

Conclusions

The social relations among elderlies had a positive effect on their mental health: The more frequent MN were held, the less risk of depressive symptoms occurred. However, the effect may vary depending on their living arrangement and environment. Thus, policies or programs targeting to enhance geriatric mental health should consider different socio-cultural backgrounds among elderlies.

INTRODUCTION

Unfavorable socioeconomic conditions among the elderly act as social determinants of health that both directly impact their health and interact with other factors [1]. Poor social conditions increase the risk of geriatric depression. Race, sex, social relations, family structure, education level, area of residence, income, and living arrangement (alone or in a nursing home) have been found to affect depression among the elderly [2]. In particular, the social relations may vary in terms of characteristics and subjective meanings experienced by the elderly depending on the environment. Also, the impact of social relations on health differs according to structural conditions on a macroscopic level [3]. These upstream factors include cultural elements such as social norms and values, socioeconomic elements such as the labor system and income level, political elements such as legislation and policies, and social changes triggered by large-scale events such as pandemics or economic recessions [3]. In particular, the effect of social relations may vary based on social capital, which refers to the material and psychological resources acquired as a result of belonging to the social network of a certain group. The impact of social relations on health may differ between bonding social capital, which occurs among members who share similar characteristics, and bridging social capital, which encompasses members with various backgrounds [3].

Previous studies have observed the preventive effects of social relations on depression [4,5]. In Korea, social relations have been measured and evaluated for their correlation with depression in terms of the following: appraisal social support, belongingness social support, loneliness [6], variety of associations [7], numbers of friends and neighbors, frequency of remote contact, frequency of visits [8,9], volunteer work, use of senior centers, participation in social groups, participation in community classes [10], and the the Korean version of the Lubben Social Network Scale [11,12]. Because the impact of social networks may differ based on the characteristics and conditions of individual elderly, subjects need to be classified into smaller subgroups, and various types of effects—such as mediating effects and moderating effects—should be taken into consideration [13]. This study focused on living arrangements and area of residence as factors that influenced the effects of social relations on depression. The number of the elderly who live alone is steadily rising in Korea [14], and living alone poses a risk of depression [15,16]. In addition, living alone has been found to moderate the effect of social integration on depression [10]. Area of residence must also be considered as a factor constituting the context of social relations. In previous studies, the factors associated with depression varied between urban and rural areas [17], and the effects of social factors on geriatric depression were dependent on the country and area of residence [18]. Bridging social capital may be more prominent in urban areas, whereas bonding social capital may be more dominant in rural areas [7]. Assuming that the characteristics of social capital impact the effects of social relations, the effects of social relations may vary depending on the area of residence.

While many studies have investigated how social relations influence depression, and some of these studies have included singular moderating variables and stratification variables [7,10,18], no studies have yet been conducted on how moderating effects vary with context. This study used meetings with neighbors (MN) as the operational definition of social relations and aimed to observe changes in the effects of social relations on depression according to the elderly’s living arrangements and areas of residence. In addition, this study aimed to verify the differences in the moderating effects of living alone according to the area of residence. The hypotheses of this study were as follows: (1) social relations among the elderly reduce depressive symptoms, (2) living arrangement (living alone or living with others) of the elderly has a moderating effect on the relationship between social relations and depressive symptoms, and (3) the effect of social relations and the moderating effect of living arrangements varies according to the area of residence.

METHODS

Data Source

This study used biannual data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA) conducted from 2006 to 2018. The KLoSA is a panel dataset that examined various aspects of the aging population, specifically Koreans aged 45 and over, in order to supply basic data for policy development and academic research [19]. The target population of the present study was individuals aged 65 and older who had previous measurements for depressive symptoms values, thereby eliminating wave 1. Among the 25 042 observations that met the criteria, 1794 (7.2%) were excluded due to missing values, and an unbalanced panel composed of 23 248 observations was ultimately constructed (Supplemental Material 1).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 10 (CES-D-10), which measures the severity of depressive symptoms, outcome variables were dichotomized with a score of 4 points as the cut-off [20]. The CES-D-10 is an extensively applied tool for measuring depressive symptoms, and after verifying its validity and measurement invariance, it was determined that the measured scores were appropriate for intergroup comparisons [21].

Social relations

The explanatory variable MN was measured using the question, “Do you have nearby friends, relatives, or neighbors, and, if so, how often do you meet?” Possible answers were divided into 2 categories, with “less than once a week” and “once a week or more.” In previous studies, frequent meetings with non-family members such as friends and neighbors were found to be associated with lower mortality rates [22].

Living arrangement and residential area

Living arrangements—the moderating variable—were classified as either “living alone” or “living with others.” For the area of residence—the stratification variable—large cities were defined as metropolitan areas with “dong” (neighborhood) unit districts, small and medium cities were defined as provinces made up of “dong” (neighborhood) unit districts, and rural areas were defined as provinces made up of “eup” (township) and “myeon” (town) unit districts.

Covariates

The control variables included age, sex, education, income, economic activity status, religion, subjective health status, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), chronic diseases, relationship with children, and previous depressive symptoms [23]. Age groups were divided into 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and 85 and older, and sex was classified as either male or female. Education level was classified into 2 categories (9 years and more [middle school degree or higher] or less than 9 years), and income was divided into quartiles of total annual income. Religion was categorized as no religion, Buddhist, Protestant, Catholic, or other. Relationship with children reflects both the frequency of remote contact and in-person meeting, and each was classified into 2 categories, with “less than once a week” and “once a week or more.” Though relationships with children can be considered an element of social relations, it was used as a control variable in this study since the difference in the effect of this variable according to the socio-cultural environment was predicted to be not significant. Health status included the participants’ subjective health status, IADL, and chronic diseases. The responses for subjective health status were classified into 2 sub-categories—”very good,” “fairly good,” and “average” were categorized as “good” while “bad” and “very bad” were categorized as “bad.” The IADL was classified into two categories, if there were any aspects of needs for assistance in daily life, it was categorized as “limited.” Chronic diseases were divided into 2 categories based on any history of previous diagnoses.

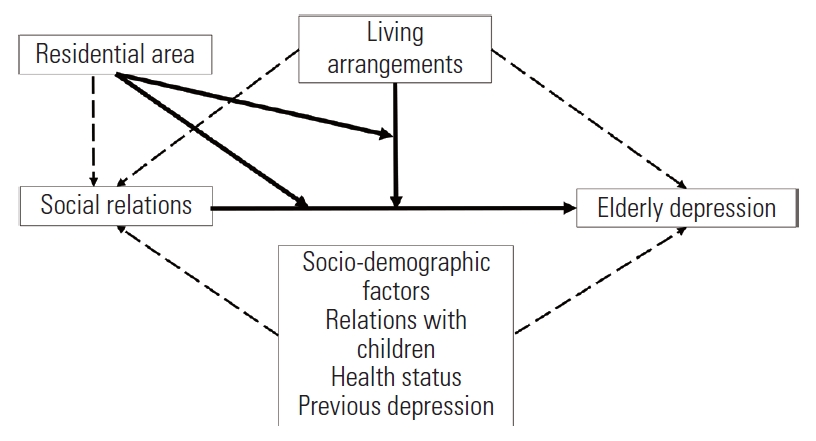

Statistical Analysis

Figure 1 is a causal graph that depicts the associations between variables. The generalized estimating equation (GEE), which incorporates the autocorrelation problem of the data based on the assumption of a working correlation matrix, was used for the analysis [24]. Since living arrangements do not change greatly with time, social relations could not be regarded as independent from unmeasured heterogeneity, and since the focus of the study was the effect at the population level, a GEE model was determined to be most appropriate [25]. In model 1, the effect of social relations was identified using univariate analysis. In model 2, living arrangements were added, and in model 3, the moderating effect of living arrangements on social relations was identified with an interaction term. In models 4 to 6, the adjusted effect was identified by adding control variables to models 1 to 3. Model 6 is shown below, and subgroup analysis was performed to make inter-regional comparisons to identify differences in the effects of social relations according to living arrangement and area of residence.

The quasi-likelihood under the independence model criterion (QIC) value of the model was compared among the working correlation structures and the independent correlation structure, with the lowest QIC value being used for the analysis. Stata version 14 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) was used as the statistics package.

Ethics Statement

The authors of this study submitted the research proposal to the Seoul National University Institutional Review Board, and an exemption was approved (IRB No. E2104/002-001).

RESULTS

The proportion of elderly who met with close neighbors more than once per week was highest in rural areas (74.0%), followed by large cities (63.0%) and small and medium cities (56.1%), while the proportion of elderly who lived alone was highest in rural areas (20.0%), followed by large cities (18.5%) and small and medium cities (18.2%). The proportion of elderly who suffered depressive symptoms was highest in small and medium cities (54.1%), followed by rural areas (53.4%) and large cities (49.0%) (Table 1).

Table 2 shows factors related to depressive symptoms among all of the study participants. In model 1, MN was found to be associated with a reduced risk of depressive symptoms (odds ratio [OR], 0.56; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52 to 0.60), and in model 2, living alone was found to be associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.52 to 1.81). However, in model 3, the moderating effect of living alone on the effect of social relations was found to be insignificant. The size of the effect in models 4 to 6, to which control variables were added, was slightly lower, but the direction and significance remained similar.

Generalized estimating equation models for associations between depressive symptoms and related factors among Korean seniors

Table 3 shows the outcome of the subgroup analysis performed using the GEE for models 5 and 6 according to the area of residence. In model 5 of each area, the effect of MN on depressive symptoms was greatest in small and medium cities (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.52), followed by rural areas (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.73) and large cities (OR, 0.76; 95% CI 0.69 to 0.85), while the effect of living alone was greatest in large cities (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.29 to 1.68), followed by small and medium cities (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.45) and rural areas (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.37). When comparing model 5 and model 6, model 5 was most appropriate for large cities and small and medium cities whereas model 6 was more appropriate for rural areas. The moderating effect of living alone was found to be significant only in rural areas (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.92).

Regional comparison of generalized estimating equation models for associations between depressive symptoms and related factors among Korean seniors

Figure 2 shows the different effects of MN on depressive symptoms according to living arrangements for each region. MN showed a clear effect in terms of reducing the risk of depressive symptoms among the elderly who lived alone in rural areas compared to their counterparts who lived with others.

DISCUSSION

In the descriptive analysis, half of the elderly overall were found to have experienced depressive symptoms. In the 2017 Survey of the Living Conditions of the Elderly, only 3.0% of the elderly were diagnosed with depression [26]. However, even taking into consideration that not all depressive symptoms meet the medical diagnostic standards of major depressive disorders, it is likely that the depressive symptoms of many elderly people are not adequately managed. While mental health promotion programs conduct screenings for depression and make efforts to improve public awareness of depressive disorders in Korea, the service usage rate is still inadequate, and the rate of antidepressant use in Korea is among the lowest of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member countries [27]. Since the elderly are at greater risk of depression than other age groups, more policy efforts are needed to identify and manage their depression.

The elderly in rural areas met with close neighbors more frequently than their counterparts who lived in large or small and medium cities. This implies that bonding social capital may be relatively dominant in rural areas. The previous studies have shown differences in local social capital between residential areas in Korea: The level of trust among neighbors and the adherence to social norms were higher in rural areas than in large cities. In addition, rural residents perceived social networks as more favorable, whereas organizational activities seeking private profit were less active among them [28]. These findings support the interpretation that bonding social capital is more commonly found in rural areas, whereas bridging social capital is more common in urban areas.

The GEE model analysis suggested that MN was associated with a reduced risk of depressive symptoms. The results of earlier studies also support the finding that frequent meetings with close neighbors have a protective effect on depression [29,30]. Based on the previous study that analyzed the mechanism of depression-alleviating effects of social relations [3,31], the results of the present study suggest that the exchange of social support plays an important role in the effects of MN. According to the Survey of the Living Conditions of the Elderly, 78.2% of the elderly met with friends, neighbors, and acquaintances more than once per week. This proportion was higher in the following conditions: in rural areas, among women and employed elderly. Also, the frequency of meetings was higher among elderlies with poor socioeconomic conditions including those who lived alone, were uneducated, and had a low income [26]. These results are possibly due to the elderly trying to resolve their socioeconomic hardships through social relations. Thus, it is necessary to promote positive mutual exchange such as informal group reunions since relationships with neighbors are a key component in the lives of the elderly. Also, both tangible and intangible resources needed to sustain social relations should be supported. Facilitating informal group participation may be an effective measure to do this [32].

The results of inter-regional comparisons showed that the effects of MN were greatest in small and medium cities, followed by rural areas and large cities. While the high level of heterogeneity in small and medium cities makes it difficult to draw a collective conclusion, these results suggest the existence of a set of characteristics that makes these areas more than simply a mid-level group that shares the traits of both large cities and rural areas. When comparing large cities to rural areas, the protective effect of meeting close neighbors on depressive symptoms was found to be greater in rural areas. Also, the moderating effect of living alone on the effect of MN was significant only in rural areas. Such outcomes may indicate that social relations had a more dynamic effect on depression in the context of bonding social capital, in which strong ties among members are prominent [3]. Though living alone showed negative moderating effects in this study, the effect of social integration (volunteer work, use of senior centers, participation in social groups, participation in community classes) on depression was greater among the elderly who lived alone in a previous study [10]. These conflicting results of the moderating effect may imply that the socio-cultural context of living alone worked in a different way between public social integration and private social relations. Therefore, interactions between various socio-cultural factors must be taken into consideration when addressing the mental health of the elderly in different settings [18].

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the possibility of reverse causality was not completely excluded. An intuitive method of identifying causality is by reflecting the chronological sequence in the model; however, the survey interval was considered too long to hypothesize that previous social relations would determine depression at a later time. Second, the area of residence was not categorized in full detail. Therefore, the causes of the differences according to the area of residence could not be sufficiently verified. Future studies with a more detailed hypothesis should be conducted that procure further segmented regional data and data on regional community resources.

This study identified the following results. First, meetings with close neighbors were found to be associated with a reduced risk of depressive symptoms. Second, meetings with close neighbors showed smaller effects among the elderly who lived alone than among the elderly who lived with others. Third, the moderating effect of living arrangements was only significant for the elderly who lived in rural areas. In addition, the effect of social relations was greater among the elderly who lived in rural areas than it was among the elderly who lived in large cities. Therefore, a detailed approach is needed to be taken when designing and implementing interventions that incorporate social relations in which the sociocultural environment and conditions are fully considered. For example, while the elderly who live alone may be more vulnerable to depression than the elderly who live with others, the preventive effect of social relations on depression among the elderly who live alone may be more limited than it is among the elderly who live with others in rural areas. Thus, a simple and unified approach may not be effective at resolving health problems among the elderly and could even further aggravate existing health inequality.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.21.337.

Korean version is available at https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.21.337.

Flowchart of participant selection for the analysis

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

FUNDING

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: CK, CYK. Data curation: CK. Formal analysis: CK. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: CK, EJC, CYK. Project administration: CK. Visualization: CK, EJC. Writing – original draft: CK. Writing – review & editing: CK, EJC, CYK.