Factors Associated With Quitting Smoking in Indonesia

Article information

Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to identify factors associated with quitting smoking in Indonesia

Methods:

Data on 11 115 individuals from the fifth wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey were analyzed. Quitting smoking was the main outcome, defined as smoking status based on the answer to the question “do you still habitually (smoke cigarettes/smoke a pipe/use chewing tobacco) or have you totally quit?” Logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with successful attempts to quit smoking.

Results:

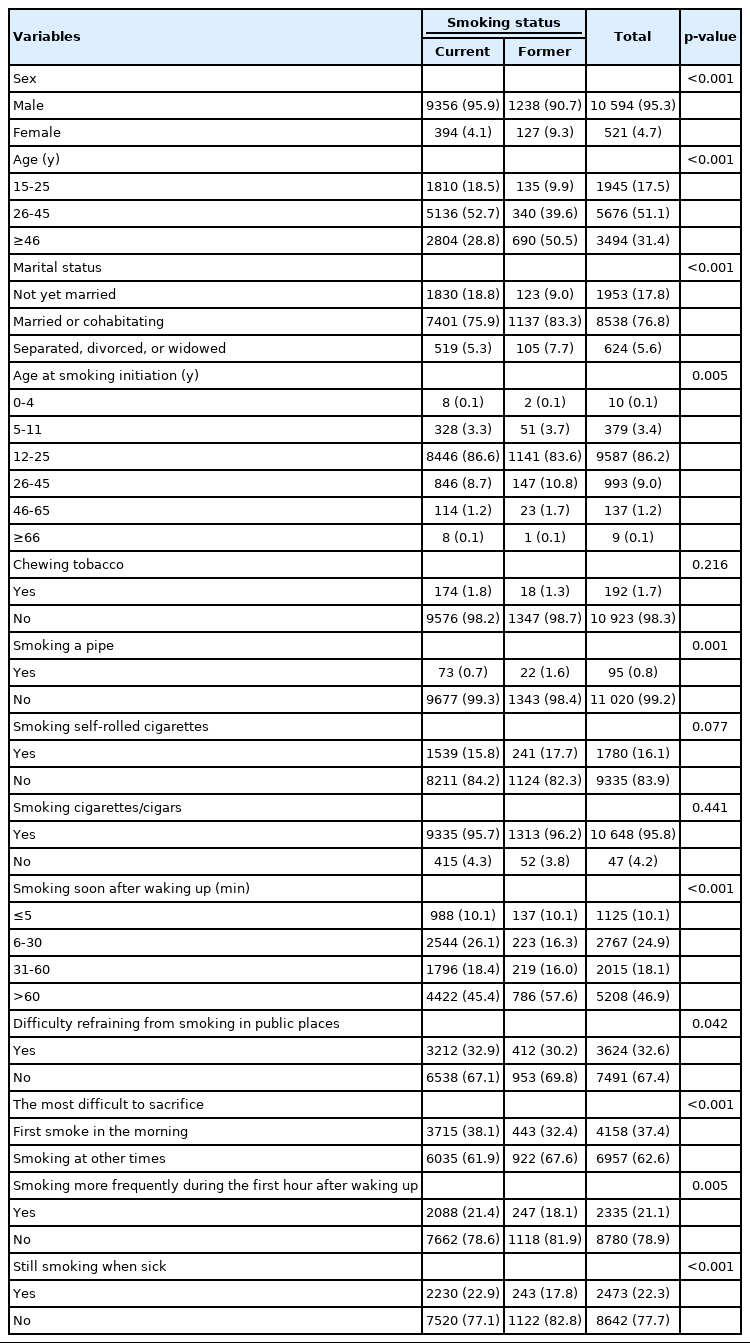

The prevalence of quitting smoking was 12.3%. The odds of successfully quitting smoking were higher among smokers who were female (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.08 to 3.33), were divorced (aOR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.82 to 3.29), did not chew tobacco (aOR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.79 to 5.08), found it difficult to sacrifice smoking at other times than in the morning (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.46), and not smoke when sick (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.54). About 59% of variance in successful attempts to quit smoking could be explained using a model consisting of those variables.

Conclusions:

Female sex, being divorced, not chewing tobacco, and nicotine dependence increased the odds of quitting smoking and were associated with quitting smoking successfully. Regular and integrated attempts to quit smoking based on individuals’ internal characteristics, tobacco use activity, and smoking behavior are needed to quit smoking.

INTRODUCTION

Smoking is the most common preventable cause of death, but about 1.1 billion adults continue to smoke globally and at least 367 million use smokeless tobacco [1]. In Indonesia, the prevalence of tobacco smoking decreased from 29.3% (2013) to 28.8% (2018) in individuals aged ≥10 years, but it increased from 7.2% (2013) to 9.1% (2018) in those aged 10-18 years and remained higher than the national target (5.4%) in 2019 [2,3]. A summary of MPOWER measures in Indonesia showed no changing trends in the affordability of cigarettes since 2008, and compliance with smoke-free policies was minimal (level 4) [2].

Indonesia has a national quitline to help smokers quit, but it has not been effective [2,4]. Only 15.7% of smokers have been reported to successfully quit smoking in Indonesia, lower than the corresponding proportions in Korea (41.2%) and South Australia (22.4%) [5]. Quitting smoking is challenging; prior research found that over 60% of smokers intended to quit and over 40% had attempted to quit [1]. Studies found that motivational factors and past attempts to quit were predictive of making attempts to quit, but not for success [6-8]. Without cessation assistance, only 4% of attempts to quit tobacco use were successful [1]. A study conducted by the Institution to Address Smoking Problems (Lembaga Menanggulangi Masalah Merokok) among 375 respondents found that 66.2% had tried to quit and failed, while 42.9% of those who unsuccessfully quit did not know how to quit smoking [8,9].

According to the theory of planned behavior, the immediate precursor of quitting smoking is an individual’s intention, or how hard someone is willing to try or how much effort her or she plans to exert in order to quit [10]. Important factors for advocating and promoting health-relevant include some internal factors (knowledge about risk factors and risk reduction; attitudes, beliefs, and core values; social and life adaptation skills; psychological disposition; and aspects of physiology) and external factors (social support; media; socio-cultural, economic, and political factors; biological factors; the healthcare system; environmental stressors; and societal laws and regulations) [11]. Age, income, smoking behavior, age at first smoking, direct cigarette costs, high education attainment, employed, and satisfaction from work affected the decisional balance in smoking cessation and were associated with long-term quitting in both female and male smokers [12-14].

Studies in Indonesia found that external factors such as the absence of family members who smoked at home, being informed of household smoking restrictions and the harmful effects of cigarettes, and being unexposed to cigarette advertisements were important factors for successful smoking cessation [5,8]. However, since quitting smoking is a complex behavior, the role of internal factors remains to be clarified. Therefore this study aimed to support previous studies by identifying associations between internal factors and successfully quitting smoking. Its findings are hoped to serve as basic data for planning tobacco dependence treatment based on smokers’ characteristics, with the goal of helping them to quit smoking.

METHODS

In this cross-sectional study, data on 11 115 individuals (4.7% female) aged 15 years and older from the fifth wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS) were analyzed. The IFLS is an ongoing longitudinal survey with a sample representing about 83% of the Indonesian population living in 13 of the country’s 26 provinces. The survey contains a wealth of information collected at the individual and household levels, including multiple indicators of economic and non-economic well-being (education, health status, etc.) [15].

The main outcome was quitting smoking defined based on individuals’ smoking status at the time of the interview. It was identified based on the answer to the question “do you still habitually (smoke cigarettes/smoke a pipe/use chewing tobacco) or have you totally quit?” Individuals who responded that they had quit were categorized as former smokers.

Thirteen exposure variables were analyzed because of their potential association with successfully quitting smoking: sex, age, marital status, age of smoking initiation, chewing tobacco, smoking a pipe, smoking self-rolled cigarettes, smoking cigarettes/cigars, smoking soon after waking up, difficulty refraining from smoking in public places, when (during the day) participants found smoking to be most difficult to sacrifice, smoking more frequently during the first hour after waking up, and still smoking when sick.

The chi-square test was used to compare differences in proportions between categorical variables, while logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with successful attempt to quit smoking. Associations between exposures and the outcome were quantified using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Using the backward elimination method, all variables were included in the initial model and mutually adjusted. The final model of successfully quitting smoking consisted of statistically significant variables after adjustment for the other covariate variables.

Ethics Statement

This study does not have institutional review board approval number since it uses secondary data of existing data (IFLS). The data are public use data sets, open access by visiting the website, do registration then download it. The website is https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral-policy/data/FLS/IFLS/access.html.

RESULTS

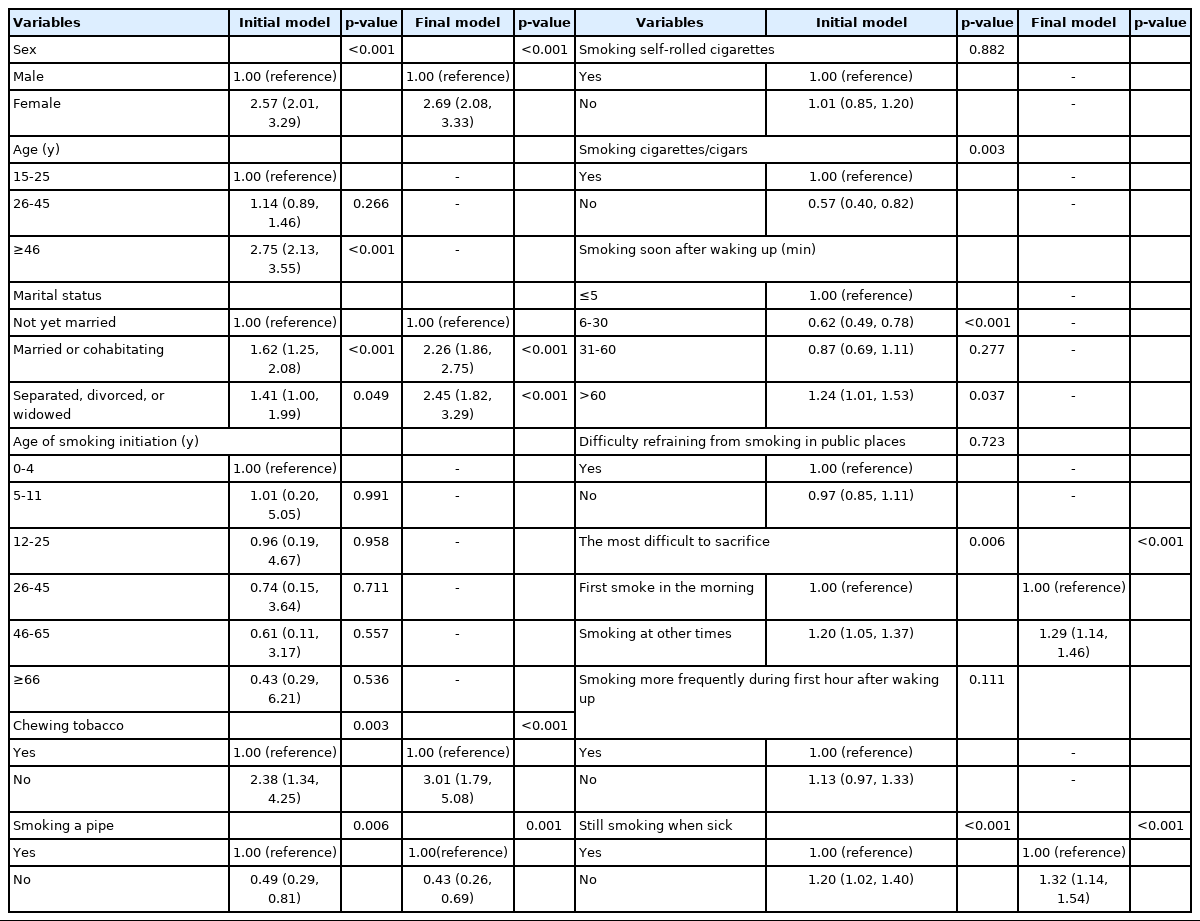

Among 11 115 ever-smokers, 12.3% had totally quit. Their median age was 37 years (range, 15 to 94), and 86.2% had started to smoke regularly in the age group of 12-25 years old. The most prevalent type of tobacco use was smoking cigarettes/cigars (95.8%). Smoking a pipe was the only type of tobacco use that showed a significance difference between current and former smokers. Furthermore, 10.1% smoked within 5 minutes after waking, 32.6% had difficulty refraining from smoking in public places, 21.1% smoked more frequently during the first hour after waking, and 22.3% smoked while sick (Table 1).

Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics, smoking behavior, and smoking status in Indonesia

Eight of the 13 variables showed significant associations with quitting smoking (Table 2). Specifically, sex, age group, marital status, not smoking a pipe, not having difficulty refraining from smoking in public places, not finding it difficult to sacrifice smoking at other times than in the morning, not smoking more frequently during the first hour after waking up, and not smoking when sick were associated with higher odds of successfully quitting smoking (OR>1.00, p>0.05).

Associations of socio-demographic characteristics and smoking behavior with smoking status (being a former smoker) in Indonesia

As shown in Table 3, all variables were analyzed to build a predictive model of successfully quitting smoking. After controlling for the other covariates, six variables showed significance in the final models: sex, marital status, not chewing tobacco, not smoking a pipe, difficulty sacrificing smoking at other times than in the morning, and not smoking when sick.

The formula of the final model to explain successfully quitting smoking was derived based on data in Table 4. The logit model of successfully quitting smoking is as follows: (Y)=-3.38+0.97 (sex)+0.82 (marital status [married])+0.89 (marital status [divorced])+1.10 (chewing tobacco)−0.84 (smoking a pipe)+0.25 (the most difficult time to sacrifice smoking)+0.28 (smoking when sick). The performance of the final model was 59% (95% CI, 58 to 60).

As an example, the logit model for a male smoker who was married, did not chew tobacco but smoked a pipe, found it difficult to sacrifice smoking at other times than in the morning, and still smoked when sick would be as follows:

Y=- 3.38+0.97 (0)+0.82 (1)+0.89 (0)+1.10 (1)−0.84 (0)+0.25 (1)+0.28 (0)

The probability of successfully quitting smoking=1/1+EXP [-(-1.21)]=1/(1+3.35)=0.23

Thus, the probability of successfully quitting smoking would be 23% in this case.

DISCUSSION

Of the 12.3% of smokers who successfully quit smoking, 9.3% were females, 50.5% were ≥46 years of age, 83.3% were married, and 83.6% had started smoking regularly in the age interval of 12-25 years old. Sex, age, marital status, tobacco activity (smoking a pipe), smoking behavior (difficulty refraining from smoking in public places, the most difficult time to sacrifice smoking, smoking more frequently during the first hour after waking up, and still smoking when sick) were associated with successfully quitting smoking. However, only sex, marital status, tobacco activity (chewing tobacco, smoking a pipe), smoking behavior (the most difficult time to sacrifice smoking, smoking when sick) were statistically significant after adjustment for the other covariate variables to explain successfully quitting smoking. This final model was organized to include each important variable and to avoid redundancy among variables for nicotine dependence.

Internal factors such as sex and marital status were associated with successfully quitting smoking. In Indonesia, stereotypical societal values and cultural disapproval of smoking among females still play an important role. Female smokers are stigmatized as morally flawed since they are promoted as the guardians of their families’ health [16]. However, this stigma could be reduced by perceptions of modernity in which smoking by female is considered more acceptable. This concept shifted smoking promotional material from focusing on a macho image to portraying smoking as part of a glamorous or otherwise desirable lifestyle [16,17].

Support from one’s spouse has been found to affect the success of quitting smoking [18-20]. A smoker’s spouse could help the smoker to find the best way attempt to quit smoking. A person in a partnership might influence his or her partner’s behaviors though a direct physical intervention (spillover effect). Females were more likely to control their spouse’s health than males. A study found that husbands with wives who did not smoke were more likely to successfully quit smoking due to the wives’ influence on their daily habits, including monitoring health, social behavior, and providing support for behavioral changes. Meanwhile, the presence of a husband who did not smoke only influenced quitting smoking for highly educated wives [20]. A possible explanation for this finding among females is that a high education level increases one’s knowledge, making one more likely to respond to a positive influence in this domain.

Using smokeless tobacco products combined with smoking cigarettes reduced the likelihood of quitting smoking. The odds of successfully quitting smoking were lower among smokers who did not smoke pipes. However, it should not be concluded that smoking a pipe is harmless and could be a desirable alternative for quitting smoking. Smoking a pipe is as harmful as, and perhaps more harmful, than smoking cigarettes [21]. The systemic concentrations of nicotine in pipe smokers was found to be high, about two-thirds the concentration found in cigarette smokers [22].

Even though the age of smoking initiation was not significant for explaining successfully quitting smoking in this study, it is an important variable in relation to the level of nicotine dependence. Age at smoking initiation has been found to be inversely associated with nicotine dependence; the earlier individuals started to smoke, the more difficulty they had quitting smoking [23-25]. High nicotine dependence was found among those who started smoking regularly under 18 years of age in comparison to those who started at age 21 or older [24]. A study among smokers in Kerala, India found that Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) scores increased with age [26].

The symptoms of nicotine withdrawal have been identified as a major barrier to quit smoking, and smokers who attempt to quit may not be well-educated about these symptoms. Nicotine use results in significant changes in the brain that make people want to smoke regardless of the long-term negative consequences. Long-term smoking also causes unpleasant psychological and physiological withdrawal symptoms when an individual stops. Smokers start to experience impairment of mood and performance within hours of their last cigarette. These effects are completely alleviated by smoking a cigarette [27,28].

A habit of smoking in the morning was found to be the behavior that most significantly affected nicotine dependence as measured using the FTND [29]. Craving and negative affect were the nicotine withdrawal symptoms most predictive of relapse, including urges to smoke that were experienced immediately after awaking in the morning [30]. A linear relationship was found between the latency until smoking in the morning and the lapse, relapse, and lapse-relapse latencies. An increase across each category (smoking within 5, 6-30, 31-60 and after 60 minutes) tended to be associated with meaningful increases in lapse and relapse latencies [30-32]. Specifically, smokers who waited a shorter time before smoking their first cigarette, were more likely to have high nicotine dependence. Due to the short half-life of nicotine, the plasma nicotine levels of very dependent smokers becomes exhausted by the time that they wake up. These smokers tend to experience great discomfort if they do not smoke their first cigarette quickly in the morning [32]. Each cigarette immediately decreases the craving, but desensitizes nicotine receptors and increases their number, thus increasing the urge for the next cigarette.

Since nicotine dependence has two components, physical dependence and psychological dependence, tobacco consumption is not driven by the frontal cortex, but rather by a non-conscious part of the brain not controlled by will (nucleus accumbens). During tobacco dependence initiation, smokers must raise the amount of nicotine administered in order to recreate the intense sensations they previously experienced. After the initial adaptation period, smokers need their individual dose of nicotine in order to feel a neutral state and to prevent withdrawal symptoms [33]. This morphological adaptation occurring in the central nervous system corresponds to the development of physical dependence, leading smokers to continue smoking even when sick.

Since this study used secondary data, a limitation relates to the validity of self-reported data such as age at smoking initiation and smoking status, which were not biologically validated and therefore might have been influenced by recall bias. The cross-sectional design also limits the ability to draw conclusions regarding the directionality or causal relationship of the findings. Despite these limitations, a major strength of this study is the amount of data from a representative sample of the Indonesian population.

Sex, marital status, chewing tobacco, smoking a pipe, not smoking in the morning, and not smoking when sick were factors with explanatory power for successfully quitting smoking. Regular and integrated support including concomitant therapeutic education, behavioral support, and pharmacotherapy should be provided to help individuals quit smoking.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

FUNDING

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All work was done by RAIS.