Perceptions of Contraception and Patterns of Switching Contraceptive Methods Among Family-planning Acceptors in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

The perceptions of family-planning (FP) acceptors regarding contraception influence the reasons for which they choose to switch their method of contraception. The objective of this study was to analyze the perceptions of contraception and rationales for switching contraceptive methods among female FP acceptors in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia.

Methods

This study involved the analysis of secondary data from the Improve Contraceptive Method Mix study, which was conducted in 2013 by the Center for Health Research, University of Indonesia. The design of the study was cross-sectional. We performed 3 stages of sampling using the cluster technique and selected 4819 women who were FP acceptors in West Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia as the subjects of this study. The data were analyzed using multiple logistic regression.

Results

The predominant pattern of switching contraceptive methods was switching from one non-long-term method of contraception to another. Only 31.0% of the acceptors reported a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods given their age, number of children, and FP motivations. Perceptions of the side effects of contraceptive methods, the ease of contraceptive use, and the cost of the contraceptives were significantly associated (at the level of α=0.05) with rational patterns of switching contraceptive methods.

Conclusions

Perceptions among FP-accepting women were found to play an important role in their patterns of switching contraceptive methods. Hence, fostering a better understanding of contraception through high-quality counseling is needed to improve perceptions and thereby to encourage rational, effective, and efficient contraceptive use.

INTRODUCTION

Family-planning (FP) programs are intended to regulate fertility to improve maternal and child health. They can decrease maternal, infant, and child mortality. Globally, the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR), an indicator for FP programs, has increased significantly from 35% in 1970 to 63% in 2017. However, FP programs continue to face challenges in developing countries, including Indonesia. One of these challenges is the lack of variety of available methods of contraception. In general, only one or two methods are commonly used [1]. Although Indonesia provides universal access to various methods of FP that are safe and reliable, following the recommendations of the International Conference on Population Development in Cairo [2], the use of contraception continues to be dominated by injections (32.0%) and pills (13.6%), which are not long-term methods. Only 10.6% of the relevant population uses long-term contraception in Indonesia [3].

The selection of a contraceptive method is important for FP acceptors. Because the objective of contraceptive use is mainly to space out or limit pregnancies, FP acceptors should choose effective methods that prevent unwanted pregnancies. Therefore, individuals should consider their choices carefully when switching from one method of contraception to another. Many previous studies have investigated switches in contraceptive methods, emphasizing the patterns of and reasons for switching [4-7].

Previously reported data indicate that many Indonesian FP acceptors do not show rational patterns of switching methods of contraception. A study showed that older women prefer non-long-term methods of contraception to long-term ones [8]. The Indonesian Basic Health Research study revealed that 49.4% of women with 3 or more children tended to use non-long-term contraception [9]. High levels of discipline and control are needed when utilizing non-long-term contraceptive methods to avoid unwanted pregnancies. Of women who used a non-long-term contraceptive method for 1-3 months, 20-40% discontinued contraceptive use, which may result in unintended pregnancy [10].

Thus, it is important that women make rational choices when switching contraceptive methods in light of changes in their age, number of children, and health conditions. Such changes may affect which methods of contraception are ideal. For example, the first contraceptive method used by a woman ≤35 years old might be a short-term method because she may want to have more children. Then, after 35, it would be recommended for her to switch to a long-term or permanent method that is more effective at preventing pregnancy [11]. Women older than 35 are at a higher risk in pregnancy and delivery; therefore, long-term or permanent methods of contraception may be preferable.

In Indonesia, no studies have yet investigated FP acceptors’ rationales for switching contraceptive methods, although some studies have explored the reasons why first-time FP users may adopt a certain method of contraception. For example, the result of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey (2012) show the percentages of choice of contraceptive method and the source of information [3].

Choices to switch contraceptive methods for reasons beyond rational considerations are influenced by FP acceptors’ perceptions of specific methods, including perceptions of side effects in comparison with those of their previous contraceptive method [12], the convenience of the particular method of contraception [13], and perceptions relating to how it is used [14]. Concerns have been raised about methods of contraception in the province of West Nusa Tenggara in Indonesia. The CPR of West Nusa Tenggara is lower than the national average. Furthermore, the percentage of unmet need in this province is 14%, which is higher than the national level [3]. The objective of this study was to analyze perceptions of contraception among FP-accepting women in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia and their rationales for switching contraceptive methods.

METHODS

This study used baseline data from the Improving Contraception Method Mix (ICMM) study conducted in 2013. This was a collaborative study between the Center for Communication Program of Johns Hopkins University, the Cipta Cara Padu Foundation, and the Center for Health Research of the University of Indonesia. The ICMM study included 7500 married women of reproductive age (15-49 years old) in West Nusa Tenggara by using a 3-stage cluster sampling technique. The study design was cross-sectional. The inclusion criteria for the respondents of our study were living in West Nusa Tenggara, being married, and having ever used and using contraception. Thus, we analyzed data from 4819 women who were FP acceptors. The data were collected through face-to-face interviews with a questionnaire.

The dependent variable of this study was the rationality of respondents’ pattern of switching contraceptive methods. The criteria used to define a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods were developed on the basis of the patterns of rational use of FP presented by the National Population and Family Planning Board of Indonesia. Rationality in switching contraceptive methods means that the method of contraception is changed in accordance with a woman’s age, number of children, and FP motivation [11]. The independent variables were perceptions of contraceptive methods, including perceptions of side effects, cost, ease of use, and accessibility. Individual characteristics and FP provider characteristics were analyzed as confounding variables.

This study analyzed data using univariate and bivariate analysis. These statistical analyses were followed by multiple logistic regression analyses to confirm the influence of factors related to rational patterns of switching methods of contraception.

We controlled for individual characteristics and FP provider characteristics in order to focus on the effects of perceptions of the side effects, cost, ease of use, and accessibility of contraceptives on the likelihood of having a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods. The first step in the multivariate analyses was to include all independent variables and to obtain odds ratios (ORs) for the main independent variables (perception-related variables). The second step was to control the confounding variables. We excluded the confounders one by one, and then we observed the changes in the ORs of the perception-related variables compared with their original values. By controlling the confounding variables, we obtained adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for the perception-related variables. The analyses concluded if individual characteristics and family planning provider were not the confounder variables.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, University of Indonesia (329/UN2.F.10/PPM.00.02/2016).

RESULTS

Of the 4819 women of reproductive age, 2196 were FP acceptors over 35 years of age, of whom 80.9% expressed the motivation to space their pregnancies (Table 1). Meanwhile, among the 3232 FP acceptors who had 2 or more children, 83.4% expressed the motivation to space their pregnancies.

Characteristics, FP motivations, and patterns of switching contraceptive methods among female FP acceptors in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, 2013

As also shown in Table 1, regardless of age and number of children, among women with the FP motivation of spacing their pregnancies or limiting the number of children, the predominant tendency was to switch from a non-long-term contraceptive method to another non-long-term contraceptive method. In other words, differences in women’s circumstances led to no fundamental difference in the pattern of switching contraceptive methods. Among women who were FP acceptors, only 31.0% reported a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods.

Table 2 presents the distribution of women who were FP acceptors, based on their perceptions of their methods of contraception. Women who perceived that their contraceptive method had no side effects tended to have a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods (33.2%), unlike those who reported that their method of contraception had side effects (18.8%). Women who reported that contraceptives were not easy to use were more likely to show a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods than those who stated that contraceptive use was easy. In addition, women who reported that the cost of their method of contraception was moderate tended to have a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods.

Patterns of switching contraceptive methods according to perceptions of contraception among female family-planning acceptors in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, 2013

Furthermore, Table 3 shows that rational patterns of switching contraceptive methods were more common among women who had a higher education (45.5%), made decisions with their husbands (32.6%), and received information on contraception from an FP provider (32.4%).

Patterns of switching contraceptive methods according to knowledge level, individual characteristics, and family-planning (FP) provider characteristics among female FP acceptors in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, 2013

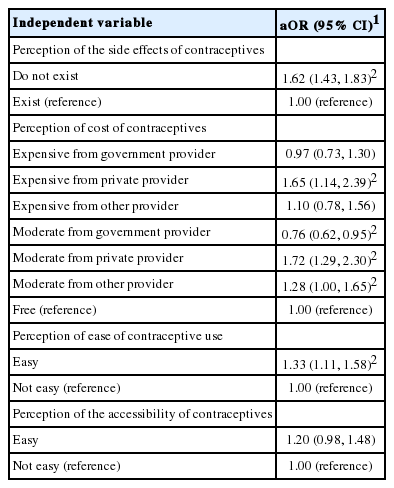

Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the relationship between perceptions of contraception and the likelihood of having a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods. When individual characteristics and FP provider variables were controlled, perceptions of the side effects, cost, and ease of use of contraceptives were significantly associated (α=0.05) with a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods.

Compared to women who perceived the cost of contraceptives to be free, those who perceived that the cost of contraceptives from a private provider was high were 1.65 times more likely (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14 to 2.39) to have a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods. Similarly, women who perceived the cost of contraceptives from a private provider to be moderate were 1.72 times more likely (95% CI, 1.29 to 2.30) to report a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods. Meanwhile, women who perceived that the cost of contraceptives from a government provider was moderate were 0.76 times less likely (95% CI, 0.62 to 0.95) to have a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods. In addition, women who perceived contraceptive use to be easy were 1.33 times (95% CI, 1.11 to 1.58) more likely to have a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods than those who perceived contraceptive use as difficult. Additionally, perceptions of the side effects of the contraceptive method had a significant impact on the likelihood of women to report a rational method of switching contraceptive methods (aOR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.43 to1.83) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that moving from one non-long-term method of contraception to another non-long-term method was the predominant pattern of switching contraceptive methods. This result is similar to that obtained by a study in southeastern Ethiopia [15], which found that 29.4% of participants had switched their contraceptive method, of whom 49.1% changed from pills to injections. In the USA, it was also found that 42.6% of married women had switched their contraceptive method from pills to condoms [16]. In fact, it appears that not all FP acceptors are willing to switch. Women older than 35 and those who have 2 or more children have motivations to limit the number of their children, meaning that high-effectiveness contraceptives are recommended for them. Therefore, a long-term method of contraception is an appropriate choice for such women [11]. However, in reality, women prefer to choose other non-long-term methods of contraception instead of long-term ones. We found that only one-third of FP-accepting women in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia had a rational pattern of switching their contraceptive method relative to their age, number of children, and FP motivation.

Our study indicated that perceptions of the side effects of methods of contraception were significantly associated with switching contraceptive methods, according to age, number of children, and FP motivation. Of the 4 perception-related variables measured in this study, perceptions of the side effects of contraception were the most influential factor in women switching contraceptive methods. Mansour [13]’s study showed that a minimum impact on health and wealth was key for the selection of a contraceptive method. Thus, improving FP acceptors’ understanding of the side effects of various methods of contraception is needed to help them consider which method is most appropriate for them and to enable them to rationally switch contraceptive methods.

This study also found that perceptions of the cost of contraceptives also influenced the pattern of switching contraceptive methods among FP acceptors. They might have had the perception that private providers offer high-quality services and can provide contraceptive methods appropriate for their need with fewer side effects. Therefore, FP acceptors preferred to obtain contraception from a private provider, although doing so is a more expensive option than obtaining contraception from a government provider. Our study is supported by the findings of Korachais et al. [17], who concluded that the demand for contraception was not cost-sensitive among users in low-income and middle-income countries. The present study also found that the likelihood of having a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods was higher among women who had specific perceptions about the cost of contraceptives obtained from private providers.

This study also analyzed the perceptions of contraceptive use. Women tend to switch to methods of contraception that are easy to use [4,13,14]. However, methods of contraception that are easy to use may be not effective for fertility reduction. Our study found that FP acceptors believed that non-long-term contraceptive methods, such as injections and pills, were easy to use. Parajuli et al. [14] found a similar result, concluding that oral contraceptive pills were felt to be easier to use. Contraceptive methods perceived as not easy to use included those requiring an invasive intervention or surgery, such as intrauterine devices, implants, and sterilization, which prompted fear among FP acceptors. However, we found that FP acceptors who perceived that their method of contraception was difficult to use nevertheless were more likely to have a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods. This may have been because women understood which method of contraception was most appropriate for their present condition. FP acceptors with a solid understanding of contraceptives tend to be loyal to their selected method [18]. More information is needed on FP acceptors’ rationales for selecting a method of contraception, and knowledge about how contraceptive methods are used is needed to help reduce fear regarding certain contraceptive methods.

In conclusion, our study found a high prevalence of irrational patterns of switching contraceptive methods. The predominant pattern among women who were FP acceptors was to switch from one non-long-term contraceptive method to another. This may have been because the majority of women had the motivation to space out their pregnancies, not to limit their number of children. Those participants considered non-long-term contraceptive methods to be the best options. Perceptions of the side effects of contraceptive methods were among the main factors contributing to the likelihood of a rational pattern of switching contraceptive methods. Hence, information on side effects must be disseminated to improve the rationality with which FP acceptors in Indonesia choose methods of contraception.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Program and the Center for Health Research, University of Indonesia for their permission, technical assistance, and help in finalizing the manuscript. This study was supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Department Foreign and Trade (DFAT) under the Improving Contraceptive Method Mix (ICMM) project, managed by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Program. The authors also express special thanks to Mrs. Yunita Wahyuningrum, S.Sos. M.Si, and Dr. Douglas Storey, PhD for their support in the implementation of this study.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: YA. Data curation: FY, DD. Formal analysis: YA, IA. Funding acquisition: RD. Methodology: BU, IA, RD. Project administration: DD. Visualization: FY. Writing - original draft: YA, DD, FY, BU, IA, RD. Writing - review & editing: NMN.