A Comment on “Quaternary Prevention in Public Health” by Dr. Jong-Myon Bae

Article information

Dear Editor

The recent paper of Dr. Jong-Myon Bae, “Quaternary Prevention and Public Health” [1], in your journal has attracted my interest. The spread of this concept is beyond all expectation, and I am quite happy that the paper contributes to analytic thinking about the complexity of health care.

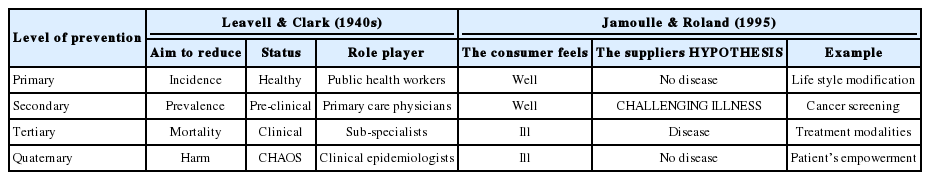

This particular application of the quaternary prevention (QP) concept is brilliant. Nevertheless, I would propose some slight modifications to Table 1 suggested by Dr. Bae, which I have taken the liberty to reproduce here with the due authorization of Dr. Bae after several rounds of correspondence with him.

The QP concept was born in Belgium in 1986. Leavell and Clark’s preventive medicine framework did not mention QP [2]. In fact, the QP concept started to diffuse at the World Organization of Family Doctors (Wonca) congress in Hong Kong in 1995. Therefore, I have added a red line to the table to distinguish the origin of each concept in the framework.

To understand the history of the QP concept, I suggest that your readers refer to the Wonca International Classification Committee web site, where the Wonca Prague 2013 poster on QP has been translated into several Asian and European languages [3].

It is worth notifyng that the concept proposed by Leavell and Clarke in the 1940s was a disease-based one, as the stages of prevention proposed are directly derived from the stages of syphilis studied by Clarke [4], while the stages I have proposed are relationship-based and thus a co-construction between the doctor and the patient.

I would also stress that the subdivision of roles among several players is unexpected but understandable in the context of severe epidemics such as Middle East respiratory syndrome. Indeed, in usual clinical practice, a family doctor is first of all a generalist and takes on all four roles, including duties in all four fields of prevention. Thus, in a hospital-based severe epidemic outbreak, the general practitioner has to be competent in all fields while taking a strong interest in clinical epidemiology.

The Status column in Table 1 with the distribution healthy, pre-clinical, and clinical is very informative. The empty space of this column in the QP row could be filled by the term ‘Chaos’. This term address the consequences of the non-agreement between the doctor and the patient as in the chaos described in the Stacey diagram [5], developed for management issues, which shows how chaos surges from the discrepancy between the meeting of the uncertainty of the supplier (here, the doctor) and the consumer (here, the patient). It also highlights how complexity is the core problem of health care [6]. Public health specialists are aware of the chaos provoked some years ago by the predicted epidemic of H1N1 [7].

I would also propose the replacement of the term ‘conclusion’ by ‘hypothesis’, more in line with the uncertainty we are facing. Lastly, and as suggested by Dr. Bae, the term ‘disease’ the doctor is looking for in the Secondary row could be replaced by ‘challenging illness’, which clarifies that in screening the doctor does not assume disease but tries to help the patient.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest with associated the material presented in this paper.