Health Impact Assessment as a Strategy for Intersectoral Collaboration

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the use of health impact assessment (HIA) as a tool for intersectoral collaboration using the case of an HIA project conducted in Gwang Myeong City, Korea.

Methods

A typical procedure for rapid HIA was used. In the screening step, the Aegi-Neung Waterside Park Plan was chosen as the target of the HIA. In the scoping step, the specific methods and tools to assess potential health impacts were chosen. A participatory workshop was held in the assessment step. Various interest groups, including the Department of Parks and Greenspace, the Department of Culture and Sports, the Department of Environment and Cleansing, civil societies, and residents, discussed previously reviewed literature on the potential health impacts of the Aegi-Neung Waterside Park Plan.

Results

Potential health impacts and inequality issues were elicited from the workshop, and measures to maximize positive health impacts and minimize negative health impacts were recommended. The priorities among the recommendations were decided by voting. A report on the HIA was submitted to the Department of Parks and Greenspace for their consideration.

Conclusions

Although this study examined only one case, it shows the potential usefulness of HIA as a tool for enhancing intersectoral collaboration. Some strategies to formally implement HIA are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Intersectoral collaboration, defined as the participation of various actors, is an essential subject of recent research and intervention in public health [1-3]. Intersectoral collaboration is important because the complexity of health determinants makes it difficult for one institution to deal with all public health problems [4]. In addition, it has been recognized that information delivery, motivation, skills, and self-confidence, which have been key strategies in health education, are not sufficient for inducing behavior changes. Instead, changes in the social and physical environment need to be made in a way that supports health [5].

Intersectoral collaboration was advocated as early as the Alma-Ata Declaration resulting from an international conference on primary health care in 1978 [6]. The first clause of this declaration states that the highest level of health requires the participation of various social and economic sectors as well as the health sector. Thirty years later, however, an evaluation of the Alma-Ata Declaration found that intersectoral collaboration had been largely ignored in various sectors, including education, agriculture, housing, and public programs [7].

In fact, intersectoral collaboration rarely occurs naturally, and therefore specially designed tools should be introduced [8]. Stead [8] categorized intersectoral collaboration in policy formation into three levels: policy cooperation as the lowest level, policy coordination as the middle level, and policy integration as the highest level. Stead [8] proposed health impact assessment (HIA), together with a sustainable development plan and strategic environment assessment, as a tool for policy coordination.

HIA is a policy tool for minimizing the possible negative health impacts and maximizing the possible positive health impacts of a policy, a plan, or a program by predicting and informing decision makers of its health impacts. HIA aims to have health considered in all policies rather than making health the top priority in all circumstances [9]. HIA was one of the priority areas during the fourth phase (2003 to 2008) of the European Healthy Cities Network and has been actively implemented in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and several Southeast Asian countries, especially Thailand.

Health impact assessment can be classified into narrow HIA and broad HIA based on the comprehensiveness of the health determinants and the acceptability of the evidence [10]. A narrow HIA, which originated from the field of environmental health, is based on toxicology and epidemiology and emphasizes the measurement and quantification of health impacts. On the other hand, a broad HIA, which originated from the holistic health model, emphasizes the value of democracy and community participation, but quantification of health impacts is relatively less appreciated. A broad HIA has greater relevance to health promotion policy because it can contribute to intersectoral collaboration as well as healthy public policy and community participation [9,11].

The merits of HIA as a tool for intersectoral collaboration for health promotion have little been explored in Korea. One study examined the potential of HIA as a tool for improving health inequality [12], and one case report of an HIA that can be classified as a broad HIA has been published [13]. Most of the HIAs reported in Korea have been narrow HIAs [13]. Overall, broad HIA has not been explored much in Korea, either in general or as a strategy for intersectoral collaboration.

The purpose of this study was to explore whether an HIA could be an effective tool for intersectoral collaboration in Korea. For this purpose, we examined the case of Gwang Myeong City, where a rapid HIA of the master plan for Aegi-Neung Waterside Park was conducted.

The Aegi-Neung reservoir was being used as a fee fishing spot. It was located in the development restriction area and had been polluted by trash and paste baits due to fishing. A good ecological pond and a wetland were located in the southern part of the reservoir, and low hills, farmlands, and the Gwang Myeong interchange were located in the western part. Mt. Gureum, Younghoewon, a historic site, and a 400-year-old nurse tree are also located near the reservoir.

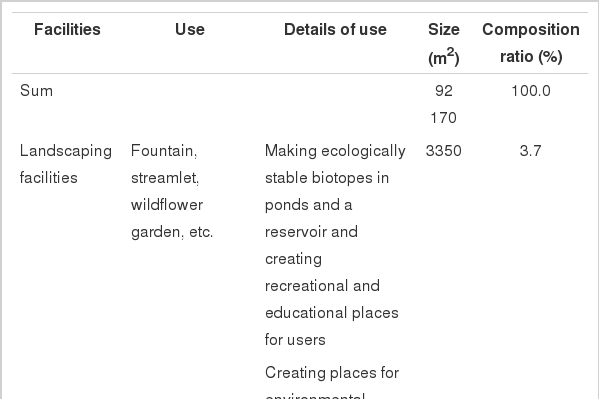

The waterside park was intended to be the center of the city's greenspace system, connecting hiking tracks, forests, and the nearby historical sites. The waterside park was also to provide places for leisure and relaxation for visitors and ecological learning for adolescents, and to become the landmark of the city. The plan was first drafted in 2008 and planned to be approved by 2011. The contents of the plan are summarized in Table 1.

METHODS

I. Rapid Health Impact Assessment (HIA)

Health impact assessment can be classified into rapid HIA, intermediate HIA, and comprehensive HIA, according to the level of resources required and the scope of health impacts being appraised [15]. Rapid HIA is the simplest type of HIA and is usually used when time and resources are limited. Rapid HIA normally takes 6 to 12 weeks and involves collection and analysis of existing literature and data to assess potential positive and negative health impacts [14]. It is the type of HIA most frequently used in practice because it requires less extensive resources than other types of HIA [15].

Rapid HIA goes through the same process as other types of HIA. It usually involves a participatory stakeholders' workshop [16]. A half-day or one-day workshop provides the participants with an opportunity to discuss health impacts from an initiative and at the same time realize democracy, which is one of the main principles of HIA [17]. Substantial evidence was found that participatory rapid HIA can be an effective tool for intersectoral collaboration or participation of interest groups, especially in European countries [10,18].

II. HIA Procedure

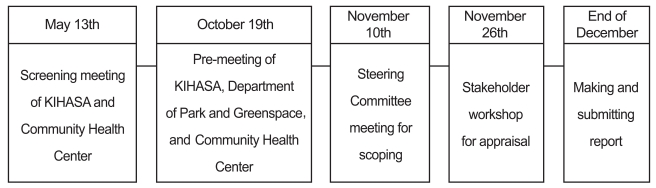

Gwang Myeong City selected Aegi-Neung Waterside Park Plan as the target of HIA according to the following process. As the screening process, the city chose 10 plans from the list of projects scheduled to be implemented in 2009, considering their size and political importance. Researchers from the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) examined the suitability of each of the 10 plans using a pre-screening tool [16]. The results of this review were then discussed with the Community Health Center of Gwang Myeong City, and three out of the ten projects were selected on 13 May 2009. Aegi-neung Waterside Plan was one of these three projects.

Before moving on to the scoping stage, a preliminary meeting took place among researchers from KIHASA who were in charge of the appraisal and civil servants from the Community Health Center and the Department of Parks and Greenspace which was in charge of the waterside park. The participants in this meeting also constituted the steering committee for the HIA. The aims of the meeting were to introduce HIA to the civil servants of the Department of Parks and Greenspace and to request data that might be needed for HIA.

Then, in the scoping stage, the steering committee met to discuss the specific assessment plan. The steering committee selected rapid HIA because of the limited time and expertise available. A number of other topics were discussed during the steering committee meeting, including preliminary positive and negative health impacts of the park plan, assessment methods and required data, and the range of the participants and their roles at the participatory workshop. Although judged by expert opinion, the positive and negative health impacts that were assessed using a comprehensive health impact checklist allowed even those new to HIA to effectively envision the HIA outputs. For instance, positive health impacts included preservation of the green fields, an increase in walking, protection of species and habitat, preservation of historical remains, decrease in community severance, and strengthening community networks.

Next, in the appraisal stage, a participatory workshop was held with the stakeholders from several sectors to overview the literature-reviewed health impacts and their evidence. After a comprehensive review on the potential health impacts, the group developed recommendations for maximizing the positive health impacts and minimizing the negative health impacts and prioritized them. Finally, a report was written by researchers from KIHASA. This report was first submitted to the Community Health Center and then to the Department of Parks and Greenspace as an official document. Figure 1 summarizes the complete procedure of the HIA.

III. Health Impact Assessment (HIA) Method

In a rapid HIA, it is common to use existing data with opinions from experts and stakeholders rather than to collect new data. In this HIA, the decision was made to use a literature review and a stakeholders' workshop. The group included ten plus the facilitator; this number was suitable to avoid neglect of minority opinions. Each decision was made by consensus. There were two members from the Department of Parks and Greenspace, one from the Department of Culture and Sports, one from the Department of Environment and Cleansing, two from the Community Health Center, two from civil society, and two residents.

The workshop was largely divided into two parts (Table 2). In the first half of the workshop, general descriptions of HIA, the Aegi-Neung Waterside Park Plan, and the health profile of Gwang Myeong City were presented. This part was carried out to allow for a general understanding of HIA before reviewing health impacts. During the latter half of the workshop, the preidentified health impacts and differential health impacts using a tool developed in England [19] and translated into Korean were reviewed and discussed, and recommendations were made accordingly. Last, the recommendations were prioritized by voting.

RESULTS

I. Community Profile

The purpose of the profile was to provide the health and socio-demographic context of the Aegi-Neung Waterside Park Plan and to clarify the potential health impacts and the particular population groups that may be affected. As of 2007, more than 316000 people (115000 households) lived in Gwang Myeong City. The area of the city was 38.5 km2. Approximately 31.53 km2 (or 81.6%) of the city was greenspace, including a limited development district, and 6.43 km2 (or 16.7%) of the area was used for residential purposes. The city was also relatively convenient for transportation and had several culture facilities and tangible and intangible cultural assets.

To characterize the health status of the population living in Gwang Myeong City, statistics from the Community Health Survey were examined. Some indicators were worse than the national average. For example, the prevalence of doctor-diagnosed hypertension was 136.4 per 1000 (national average, 129.3 per 1000). The prevalence of self-reported stress was 31.5% (national average, 27.6%). Approximately 49.8% adults experienced excessive alcohol use (national average, 45.8%). On the other hand, seemingly due to the large greenspace in Gwang Myeong City, 62.4% of adults were walking for exercise (national average, 51.4%) and 19.9% of adults (national average, 21.8%) were classified as obese (body mass index [BMI ] ≥25 kg/m2).

II. Participatory Workshop

A participatory workshop was held during the appraisal step. Various interest groups including the Department of Parks and Greenspace, the Department of Culture and Sports, the Department of Environment and Cleansing civil societies, and residents discussed the previously reviewed literature on the potential health impacts of the Aegi-Neung Waterside Park Plan. Positive health impacts were anticipated in areas including water quality and pollution, a clean city and recycling, accessibility/mobility/transport, education, leisure, community network, community development, health service, social service, physical activity, and stress. On the other hand, negative health impacts were expected in external air quality, water quality and pollution, energy consumption, noise, community safety, accidents, smoking, drinking alcohol, drugs, and sexual behavior (Table 3). After reviewing the possible health impacts, recommendations to maximize positive health impacts and to minimize negative health impacts were developed (Table 3).

III. Potential Differential Impacts Across Populations

After reviewing the potential impacts of comprehensive health determinants, the group discussed potential differential impacts across populations based on the literature review. The group identified issues of access to the park among the disabled, lower income people, and older people. On the basis of this finding, the group made recommendations to make the park more accessible to these people (Table 4).

IV. Prioritizing the Recommendations

Each participant was asked to put three stickers on his or her three most important recommendations. Using renewable energy or new energy, creating a public transport system, and securing water quality, all of which received seven votes, were the top priorities of the group.

V. Reporting

The report on the HIA, including the background, procedure and methods, and results, was first submitted to the Community Health Center for review. Then, the HIA report was submitted to the Department of Parks and Greenspace for their consideration.

DISCUSSION

Intersectoral collaboration is related to the process of decision making, and therefore the effectiveness of HIA in intersectoral collaboration can be evaluated by the extent that the health sector and other sectors collaborate. In this case study, the HIA was operated by the steering committee, which consisted of representatives from the health sector and the sector responsible for the master plan. Moreover, during the participatory workshop, the Department of Culture and Sports and the Department of Environment and Cleansing also participated. Without the HIA, the Department of Parks and Greenspace would not have involved these other sectors.

Success of intersectoral collaboration through HIA can also be evaluated based on the extent to which the common goal was achieved. The common goal of the intersectoral collaboration through HIA was to consider health in the planning of the waterside park. Impacts of the plan across comprehensive determinants of health including physical environments and social networks, as well as health behaviors, were assessed. Therefore, it can be said that health was considered by the non-health sectors through the HIA.

Although this case study found some usefulness of HIA, it would be difficult to expect ongoing intersectoral collaboration if an HIA is completed as an ad hoc program as in this case. To encourage continuous intersectoral collaboration through HIA, we should consider proper strategies, governance, capacities, outputs, and outcomes of HIA implementation [20].

First, strategies for providing a motivation for intersectoral collaboration through HIA are needed. The motivation for intersectoral collaboration could be firmly generated by a legal obligation of some kind [21]. In Thailand, for example, HIA is included in the Constitution. As a consequence, intersectoral collaboration through HIA is practiced at all levels of government. In this study, the HIA result was reported to the mayor, which is weak as an obligation. The lack of legal ground for HIA will hinder the regular practice of HIA.

Second, proper governance is necessary for HIA implementation. Governance is a system and structure that enables implementation of a plan and achievement of a goal. Governance for HIA can also be specified when HIA has a legal basis. Since there is no legal basis for HIA at the governmental level in Korea, governance for HIA is likely to be commissioned ad hoc.

Third, capacity building is needed for HIA implementation. Intersectoral leadership and mutual trust are necessary conditions for intersectoral governance [20]. One study found that the main cause of adopting HIA in decision making was the leadership of the key department [22]. In the case of Gwang Myeong City, the strong leadership of the Director of the Community Health Center encouraged the mayor to adopt the HIA program.

Leadership for HIA can be developed by education and training. However, there are few opportunities for education and training available in Korea, especially as related to health promotion. For the purpose of capacity building, education and training programs should be developed and provided to civil servants and academics. Demonstration projects can also be helpful by providing opportunities for learning by doing.

Fourth, specific outputs of intersectoral collaboration from HIA are needed. One of these outputs is whether health was considered in the decision making of the sector of interest [23]. Most HIA guidelines also recommend monitoring of the change in decision making resulting from HIA [14,24]. Visible outputs from intersectoral collaboration can help the collaboration to continue. This study, however, did not include monitoring because the final master plan had not been approved at the time of writing this paper.

Fifth, the improvement in final outcomes as well as outputs can demonstrate the value of HIA for intersectoral collaboration. Outcome indicators such as improvement of health status or reduction in health risks can provide solid evidence of the value of HIA, but extensive time and resources are required to obtain these indicators and therefore they are not practical. Quigley and Taylor [23] have recommended that we focus on whether HIA affects decision making rather than on long-term health outcomes because the purpose of HIA is to influence decision makers.

Last, we would like to discuss some of the limitations of this study. Rapid HIA in general uses qualitative evidence from a participatory workshop of interest groups as the evidence for decision making, and thus it may not be accepted in a decision environment where quantitative data and analyses are more appreciated. In addition, the result of a participatory HIA cannot be replicated, and therefore it is difficult to test its validity and reliability. Furthermore, HIA results can differ depending on who participated and who did not. In the HIA case of this study, only a few members of each sector participated, which might have undermined the representativeness of the study. In future rapid HIAs, more participants from various interest groups should be included so that the HIA can be more participatory and reliable.

In sum, rapid HIA can be an effective tool for encouraging the health sector and non-health sectors to meet and consider health in decision making. For HIA to be a continuous tool for intersectoral collaboration, we need HIA legislation, proper governance, leadership, capacity building, and monitoring of HIA results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

Notes

The authors have no conflicts of interest with the material presented in this paper.

This article is available at http://jpmph.org/.