Food is Medicine Initiative for Mitigating Food Insecurity in the United States

Article information

Abstract

Objectives:

While several food assistance programs in the United States tackle food insecurity, a relatively new program, “Food is Medicine,” (FIM) initiated in some cities not only addresses food insecurity but also targets chronic diseases by customizing the food delivered to its recipients. This review describes federal programs providing food assistance and evaluates the various sub-programs categorized under the FIM initiative.

Methods:

A literature search was conducted from July 7, 2023 to November 9, 2023 using the search term, “Food is Medicine”, to identify articles indexed within three major electronic databases, PubMed, Medline, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Eligibility criteria for inclusion were: focus on any aspect of the FIM initiative within the United States, and publication as a peer-reviewed journal article in the English language. A total of 180 articles were retrieved; publications outside the eligibility criteria and duplicates were excluded for a final list of 72 publications. Supporting publications related to food insecurity, governmental and organizational websites related to FIM and other programs discussed in this review were also included.

Results:

The FIM program includes medically tailored meals, medically tailored groceries, and produce prescriptions. Data suggest that it has lowered food insecurity, promoted better management of health, improved health outcomes, and has, therefore, lowered healthcare costs.

Conclusions:

Overall, this umbrella program is having a positive impact on communities that have been offered and participate in this program. Limitations and challenges that need to be overcome to ensure its success are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The Centers for Disease Prevention (CDC) estimates that approximately 6 adults in 10 adults in the United States of America (USA) are currently diagnosed with chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, cancer, and heart disease [1]. Despite being an advanced nation with the best healthcare facilities available, statistics suggest that the USA still has the dubious record of having the worst health outcomes [2]. This has led to an obvious strain on the healthcare system and a consequent increase in healthcare costs [3,4]. Notably, 90% of healthcare expenses in the USA are spent on treating chronic disorders [3].

The role of nutrition in maintaining health and preventing chronic disease is well-known [5]. Lifestyle modifications such as selecting foods high in nutrient density [6,7] and engaging in moderate-intensity physical activity reduce the risk of chronic diseases [8]. However, a significant challenge is the lack of consistent access to adequate food—also termed as food insecurity [9].

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has developed a Healthy Eating Index (HEI) to assess the overall diet quality. The HEI includes a set of 18 questions, formulated based on recommendations by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans [10,11], that assess a family’s difficulty in affording food on a day-today basis. A cross-sectional analysis of data derived from the 2011-2014 National Nutrition and Health Examination Survey (NHANES) found that food-insecure adults reported lower HEI scores, indicating poor diet quality. HEI was significantly higher among non-Hispanic Whites, Asians, and other ethnic minorities [12].

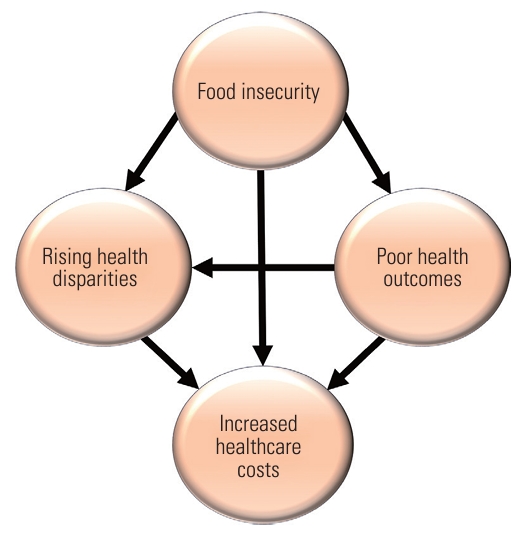

Food insecurity can stem from a variety of causes such as financial limitations, current poor state of health, lack of social support system, polypharmacy, and low literacy levels. The prevalence of food insecurity is high in ethnic minorities [13]. Food insecurity leads to serious consequences in the overall health and well-being of children by increasing their likelihood of developing iron deficiency anemia, low bone density, behavioral and social problems, infections, and need for hospitalizations, leading to poor academic performance and increased healthcare costs (Figure 1) [14]. Food insecurity is also associated with a higher risk of malnutrition, particularly in older adults [15] and corresponds to rising health disparities [16]. Food-insecure older adults may experience limitations in completing their activities of daily living [17].

Major consequences of food insecurity. Food insecurity contributes to poor health outcomes and further exacerbates health disparities in socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals and families, leading to increased healthcare burden and associated costs.

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, changes in employment status such as job loss, reduction in work hours, and lack of adequate health insurance led to increased out-of-pocket healthcare expenses, thereby increasing the risk of food insecurity [18]. Breakdowns in the food supply chain during the COVID-19 pandemic due to layoffs, especially in positions classified as non-essential, as well as the increased demand for food pushed more households toward food insecurity [19]. Before the pandemic, about 10.5% of households in the USA were food insecure; that number increased significantly in 2021 to 38% of households experiencing food insecurity [20]. Approximately 49 million people in the United States depended on food support programs in 2022 [21]. Food insecurity and chronic disease have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic [19], leading to poor mental health such as depression, anxiety, and stress [22].

Currently, federal programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC) Program, National School Breakfast and School Lunch Program, and the Congregate Meal/Home Delivered Meal Programs typically supplement individuals or households that meet eligibility criteria with food to allay some degree of food insecurity (Table 1) [23-31]. Local food banks, soup kitchens, and food pantries also contribute toward addressing the gaps that are not covered by federal programs [32]. Other programs provide nutrition assistance during certain times of the year [33], such as the Summer Food Service Program, which provides nutritious meals to low-income children during summer vacation [34], the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, which provides fruits and vegetables to children as an expansion of the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) [35], and the Farmer’s Market Nutrition Program which provides coupons for fruits and vegetables by WIC recipients and older adults. Nutrition education programs such as the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) aim to provide knowledge and access to resources that can help individuals incorporate healthy food choices [36].

SNAP is the largest federal safety net program that provides financial assistance to eligible low-income individuals and families to purchase food. The program covers about 1 in 7 Americans and provided approximately US$183 each month per qualifying individual for food-related purchases in fiscal year 2023 [37]. While SNAP has been successful in addressing food insecurity, it does not mandate participants to select nutrient-dense foods that are rich in essential nutrients. It also does not specifically focus on improving health or reducing the risk of chronic diseases, which are major public health concerns in the United States. Therefore, SNAP could be improved by encouraging participants to choose healthier food options by providing further incentives for purchasing nutrient-dense foods or by offering nutrition education programs to help participants make informed decisions about their food choices [38]. A cost-benefit analysis study conducted by Rajgopal et al. [39] that included female and male adults enrolled in the EFNEP in Virginia found that, for every dollar spent on nutrition education, an average between US$2.66 to US$17.04 was saved in healthcare costs.

Participating in the WIC can help mothers, infants, and children access healthy foods and benefit from nutrition education. In North Carolina, for every dollar spent on the WIC program, resulted in a savings of US$2.91 in Medicaid costs to cover newborn care [40].

Beyond these programs, the recently launched FIM initiative that is implemented in certain areas of the United States not only addresses food insecurity but also helps manage chronic diseases by customizing the food delivered to its recipients, making it patient-centric. This review provides more detailed descriptions of its components and their effects on the community.

FOOD IS MEDICINE INITIATIVE

The FIM initiative provides healthy food choices to qualified individuals based on the diagnosis of certain chronic diseases. Programs that fall under this category include medically tailored meals (MTMs), medically tailored groceries (MTGs), and produce prescriptions. A major benefit of FIM programs is that the prescribed food package is tailored to address the specific health needs of food-insecure individuals, whereas general food assistance programs such as SNAP, WIC, National School Breakfast Program, and NSLP, as well as meals dispersed through food banks and soup kitchens, only address food insecurity [41].

Under the FIM initiative, the Medically Tailored Home Delivered Meals Demonstration Pilot Act of 2020 requires the CDC to provide coverage for MTMs as an added benefit to Medicare recipients diagnosed with certain chronic diseases and a limiting condition [42]. Additionally, the federal government approved Section 1115 waivers for several states, including Massachusetts, Oregon, Washington, Arkansas, and New Jersey, to provide increased FIM coverage to Medicaid recipients [43]. Applications from other states are also currently being reviewed. The USDA also contributes to the FIM initiative by allowing certain high-risk patients to redeem produce prescriptions for fruits and vegetables through the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program [43]. Similar produce prescription programs are supported by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs and Indian Health Service, in collaboration with the Rockefeller Foundation. Finally, the National Institutes of Health and CDC provide funding for grants focused on best practices and interventions for the FIM initiative [43].

Preliminary studies evaluating FIM programs have indicated improvements in food security levels, health status, health outcomes, mental health, and better diet quality [44-47]. For example, a systematic review of the effects of food prescription programs on diet and cardiometabolic parameters found that increased fruit and vegetable consumption was associated with a 0.6 kg/m2 decrease in body mass index (BMI) [48]. Another study provided patients identified as food-insecure in 3 acute care clinics with a bag of food, education, and referral to community resources upon discharge. Survey results indicated that these patients felt more confident and equipped with tools and resources to address food insecurity [49]. MTGs and produce prescription programs have thus emerged as effective intervention strategies for reducing food insecurity and healthcare costs [50]. Individual evaluations of these programs are presented in the following sections.

Medically Tailored Meals

MTMs are meals recommended by a healthcare provider and approved by a Registered Dietitian based on the patient’s disease condition. MTMs typically include ready-to-eat meals and snacks that provide complete or nearly complete nutrition needs. They are usually recommended for individuals with severe or terminal illnesses who are not able to cook or go grocery shopping for food [51]. Organizations that prepare MTMs are required to use fresh ingredients with no added preservatives and need to pass safety checks through the local food safety department. The meals can either be picked up in person or can be delivered to the patient’s home. The purpose of MTMs is to improve health outcomes through better nutrition status, thereby reducing healthcare costs. Participating hospitals providing MTMs must partner with meal delivery services and retain a qualified provider such as a physician, registered dietitian, or social worker who can coordinate the meal delivery service. Upon approval, participants receive between 10 meals and 21 meals per week based on their requirements, and their situation is reassessed every 6 months. Providing tailored meals can help improve health outcomes, minimize hospital admissions, and reduce overall healthcare costs [51].

MTMs may be covered under the Medicare Advantage Program [52]. The concept of MTMs originated during the peak of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic and was broadly covered under the Ryan-White Act [53]. Several states such as California and Massachusetts, as well as Medicaid, have begun to test the effects of MTMs on health outcomes and food insecurity [41].

Berkowitz et al. [54] evaluated the benefits of MTMs in food-insecure individuals with type 2 diabetes. The randomized, crossover clinical trial study conducted over 24 weeks included 44 adults who were food insecure and had diabetes, with hemoglobin A1c levels more than 8%. Study participants received 12 weeks of MTMs, while the control group received 12 weeks of usual care with no MTMs. At the end of the intervention period, the HEI score was calculated as 71.3 for participants receiving MTMs as compared to 39.9 for participants not receiving MTMs. Importantly, MTM participants reported lower food insecurity (42%) than participants not receiving MTMs (62%).

Palar et al. [55] evaluated improvement in health outcomes in food-insecure individuals receiving MTMs. The study design was a pre-study and post-study conducted over 6 months. It included 56 adults who were below 300% of the federal income poverty level and were clinically diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and/or HIV. During the intervention period, participants received MTMs that met 100% of their daily nutrient needs. At the end of the study intervention, the percentage of individuals classified as having very low food security decreased from 59.6% to 11.5%.

Additionally, Hager et al. [56] reported that MTMs were associated with reduced healthcare costs and hospitalizations among individuals with diet-related chronic illnesses who performed limited activities of daily living.

While most referenced studies focused on the impact of MTMs on food insecurity, Berkowitz et al. [57] conducted a qualitative study that evaluated the experiences of twenty food insecure participants diagnosed with type 2 diabetes who received MTM benefits. Participants reported a positive experience in terms of better management of their diabetes, decreased levels of stress, and improved quality of life. The study also emphasized the importance of providing meals that were culturally appropriate and catered to the participant’s taste preferences.

A retrospective study was carried out in the state of Massachusetts on a sample of 1020 participants to investigate the resulting impact of MTM program participation on the utilization of healthcare services, hospital admissions, and overall healthcare costs. Participation in the program led to a decrease in medical costs per patient resulting from inpatient and skilled nursing visits. Moreover, the group that participated in the MTM program experienced more benefits than the control group that did not participate. The benefits included a significant reduction in overall healthcare costs by 16%. This was evidenced by 49% fewer hospital admissions and 72% fewer admissions to skilled nursing facilities [58].

Medically Tailored Groceries

MTGs, also called food boxes, include the distribution of unprepared or slightly processed foods for residents to consume at home. They are usually recommended for individuals who are food insecure and present with identified risks or conditions and include store-bought products or a meal kit to provide nutritionally adequate meals. These items usually require referral through a healthcare provider and are chosen by a registered dietitian. Participants in this program must have the ability to prepare a complete meal at home using the raw ingredients and be able to pick up the items from the source [59]. WIC is an example of an MTG program that covers nutritionally deficient pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, infants, and children up to the age of 5 years [24,59].

Seligman et al. [60] conducted a randomized controlled trial for 6 months in participants diagnosed with type 2 diabetes to evaluate the effect of relevant food packages on blood glucose control provided by food banks. The study included 568 food pantry participants with hemoglobin A1c ≥7.5%. Participants were provided with 11 diabetes-appropriate food packages during the study period. At the end of the intervention, while no significant changes were observed in hemoglobin A1c levels, food security significantly improved in study participants as compared to the control group.

Aiyer et al. [61] evaluated the benefits of a clinic-based food prescription program on food insecurity. The mixed-method design study was conducted over 9 months and included 172 food-insecure adults. During the intervention, 4 non-perishable food items and 30 pounds of fresh produce were distributed to each study participant every 2 weeks. The results showed that food insecurity with a baseline value of 100% at week 0 decreased to 10.2% by week 3 of intervention and was at 5.9% by week 12.

Cheyne et al. [62] evaluated the benefits of diabetes-appropriate food packages on food security and their ability to reduce risk factors for type 2 diabetes. The study model was a pre-post analysis that was conducted over 12 months on 192 adults with a history of prediabetes. Diabetes-appropriate food packages were provided to participants during the study period. Participants who reported skipping meals declined from 43.6% at baseline to 29.3% during midpoint evaluation.

Produce Prescriptions

Produce prescriptions are recommended for food-insecure individuals diagnosed with a disease condition. The prescription is provided as a voucher or a debit card that can be redeemed for produce items. Produce items are ideally fresh but can also include canned or frozen fruits with no added sugar, salt, or fat. Participants can redeem their vouchers at local farmers’ markets, grocery stores, or supermarkets and should have the ability to cook the finished product using the produce items at their place of residence [59,63].

Increased fruit and vegetable consumption can lead to better health outcomes and decrease the risk of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes [64], and yet, many individuals, especially those from a lower socioeconomic status, are unable to do so [65]. The inclusion of farmers’ markets, particularly in areas that serve individuals with heightened food insecurity rates, can provide better food choices [66]. For this reason, several incentive-based fruit and vegetable programs have been established, such as the Double Up Food Bucks program. This program allows individuals receiving SNAP benefits to double up on the benefits received if they purchase more fruits and vegetables at participating grocery stores. At the same time, the program also supports local farmers [67].

Gao et al. [68] found that produce prescriptions increased fruit and vegetable intake and decreased hemoglobin A1c levels in food-insecure individuals. Ridberg et al. [69] evaluated the effects of produce prescriptions on food security in the pediatric population. A pre-post study was conducted on 578 households identified as food insecure and included children 2-18 years of age who were overweight or at risk of being overweight. The study was performed for 4-6 months. Each participant received produce prescriptions worth US$0.50-1.00 per day for 4-6 months. Nearly 50% fewer households reported the incidence of a pediatric participant not eating food for an entire day at the end of the study period. A subsequent study by the same group determined the effects of produce vouchers on food security; however, this time, the study was focused on WIC participants and evaluated 592 pregnant women for 14 months. Produce vouchers were distributed monthly throughout the study period. Food insecurity dropped from 23% at baseline to 14% at the end of the intervention period [70].

Slagel et al. [71] performed a non-randomized, parallel control study on 36 adults identified as food insecure and having a pre-existing health condition for seven months. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the benefits of produce prescriptions on health outcomes in the study participants. Produce prescriptions were provided to participants in combination with diet education. The study noted significant improvements in overall fruit and vegetable consumption but not in overall food security level.

Bryce et al. [72] conducted a 13-week Fresh Prescription Program intervention on 65 adult, non-pregnant, low-income participants diagnosed with uncontrolled diabetes in Detroit. These participants were provided with a total of US$40 produce vouchers for 4 weeks that were redeemable at a farmers’ market (mercado) and followed up for their clinical care by a healthcare provider from a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) if they had a diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, abnormal lipid profile or obesity. FQHCs exist in areas that are considered underserved and cover wide populations that are food insecure and face an increased risk of chronic diseases [73]. While the study did not observe a significant change in blood pressure and weight among the participants (potentially due to the short study duration), hemoglobin A1c levels decreased by 0.7 percentage points [72]. A similar intervention study of 40 members of a rural community with type 2 diabetes that included 24-week of culturally tailored meals, produce prescription and nutrition handouts also resulted in decreased hemoglobin A1c levels, increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, and lower levels of perceived stress [74].

There are more ongoing studies. For example, the Nutrition to Optimize, Understand, and Restore Insulin Sensitivity in HIV for Oklahoma (NOURISH-OK) conducted a multi-level trial to determine the impact of food insecurity on insulin resistance and provide evidence-based information that will help draft effective guidelines on FIM initiatives [75].

CHALLENGES AND SUGGESTIONS

Given that the FIM programs have been recently implemented, they certainly have had their share of challenges. The impact of these programs is restricted, as only small groups of individuals qualify as beneficiaries because most of these programs are funded by short-term grants and funding sources and are based on specific criteria [76]. FIM programs would, therefore, be more impactful if integrated with large-scale community programs such as SNAP and the Congregate Meal Programs.

Additionally, many of these programs require prior approval or prescription from a physician or a healthcare provider. Therefore, incorporating nutrition education within the medical school curriculum can result in more clinicians recognizing the importance of incorporating a healthy lifestyle through diet changes in the prevention and management of chronic diseases [36]. Indeed, medical students participating in a 4-week cooking program using olive oil-based recipes reported improved nutrition knowledge [77]. Incorporating culinary skills training as part of the curriculum for clinicians can improve their nutritional knowledge and increase the incorporation of FIM in treatment protocols [78]. Application of food safety regulations and providing education on various food processing and food preservation methods can be beneficial to retailers, vendors, and manufacturers [79]. In addition, medical anthropology that includes observation of program participants on how food is incorporated into their daily dietary intake including cultural practices will improve our understanding of public acceptance of FIM initiatives [80].

A few other challenges to the FIM initiative include participants being unable to travel to a farmers’ market to redeem their food vouchers, inability to redeem vouchers before the expiration date, inadequate variety of foods or choices that are culturally tailored, low literacy rate, and lack of resources and cooking facilities at home [81,82]. A study of 27 colorectal patients noted dissatisfaction of participants in their overall experience after surgery due to a lack of adequate nutrition and diet support [83]. Providing cooking education in combination with produce prescription can lead to increased consumption of fruits and vegetables leading to improved health outcomes [84]. Establishing teaching kitchens in partnership with agricultural agencies, community gardens, and farms would improve opportunities for networking and collaboration and serve the dual purpose of educating healthcare providers on the importance of nutrition, as well as a platform where cooking classes and demos can be provided to the community members and patients [85-87], thereby enhancing the long-term success of these initiatives.

Changes in policies and legislations that help integrate public and private sector entities and include improved nutrition standards of meals provided through food assistance programs can help maintain health and prevent diseases in wider target populations [46,76,88]. Expanding nutrition education and increasing the scope of subject matter experts such as registered dietitians in providing medical nutrition therapy and drafting FIM-focused, culturally tailored meals will perhaps result in better adherence. In addition, providing subsidies, particularly for low-income families, can increase the incorporation of healthier food choices [89,90].

FIM initiatives have thus far only been evaluated in small-scale settings as compared to some of the larger food assistance programs that address food insecurity [41]. Many studies evaluating the impact of fruit and vegetable incorporation did not have an adequate sample size, and some lacked a control group [91]. Future studies need to be more rigorous and include more study participants [92]. Inclusion and eligibility criteria also need to be standardized and would particularly help in identifying coverage and reimbursement by healthcare facilities and insurance programs.

Since the studies were conducted on different age groups, comparing benefits across various populations is not fully feasible. Electronic health records should be used to evaluate the impact of FIM programs on access to healthy foods and health outcomes [93].

Importantly, since food security levels are impacted by external factors such as the economic condition of a household [13], interventions can potentially produce positive changes only as long as they are active. Further research needs to focus on studying the impact of these programs not only at the end of the study but over many years to determine long-term effects [94].

CONCLUSION

FIM initiatives appear to have a positive impact on health outcomes by lowering the impact of food insecurity during the program implementation phase. This, in turn, translates to a reduction in healthcare costs, especially for individuals with chronic diseases. A simulation model developed by researchers from Tufts University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and supported by the National Institutes of Health, used data from the NHANES to predict outcomes if food prescription policies were applied to Medicare and Medicaid. Incentives in the form of a 30% subsidy for fruits and vegetables and a 30% subsidy for other healthy foods such as whole grains, nuts, seeds, and plant-based oils were applied to estimate the savings in healthcare costs and impact on health. The study found that lifetime subsidies for fruits and vegetables would result in an increase in consumption by 0.4 servings per day, which would lead to the prevention of 1.93 million cardiovascular disease-related complications and an overall reduction in healthcare costs by US$39.7 billion [95]. Similarly, data from another computer-simulated model incorporating MTM in 6 309 998 eligible United States adults led to overall savings of US$13.6 billion and reduced hospitalizations by 1.6 million in the first year of implementation [56].

Incorporating FIM initiatives into healthcare coverage would involve integrating programs that emphasize the importance of healthy and nutritious food as a key component of healthcare. Additionally, modifying existing supplemental nutrition programs to include FIM options would provide individuals with access to meals and ingredients that are specifically designed to promote health and wellness. Long-term policy reforms are needed to systematically address issues related to food insecurity. Healthcare plans should focus on incorporating FIM initiatives and cover households affected by low food security levels to promote the maintenance of health and prevention of disease. These changes can have a significant impact on health outcomes, reducing the risk of chronic diseases and improving overall quality of life.

Notes

Ethics Statement

As this was a systematic review, data extraction was conducted solely from published articles. Therefore, no institutional review board approval was needed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to conceiving the study, analyzing the data, and writing this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.