Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Prev Med Public Health > Volume 57(3); 2024 > Article

-

Scoping Review

The Role of Pharmacists’ Interventions in Increasing Medication Adherence of Patients With Epilepsy: A Scoping Review -

Iin Ernawati1,2

, Nanang Munif Yasin3

, Nanang Munif Yasin3 , Ismail Setyopranoto4

, Ismail Setyopranoto4 , Zullies Ikawati3

, Zullies Ikawati3

-

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2024;57(3):212-222.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.23.592

Published online: April 25, 2024

- 752 Views

- 81 Download

1Doctoral Program in Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2Akademi Farmasi Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia

3Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

4Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Corresponding author: Zullies Ikawati, Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia E-mail: zullies_ikawati@ugm.ac.id

Copyright © 2024 The Korean Society for Preventive Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

-

Objectives:

- Epilepsy is a chronic disease that requires long-term treatment and intervention from health workers. Medication adherence is a factor that influences the success of therapy for patients with epilepsy. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the role of pharmacists in improving the clinical outcomes of epilepsy patients, focusing on medication adherence.

-

Methods:

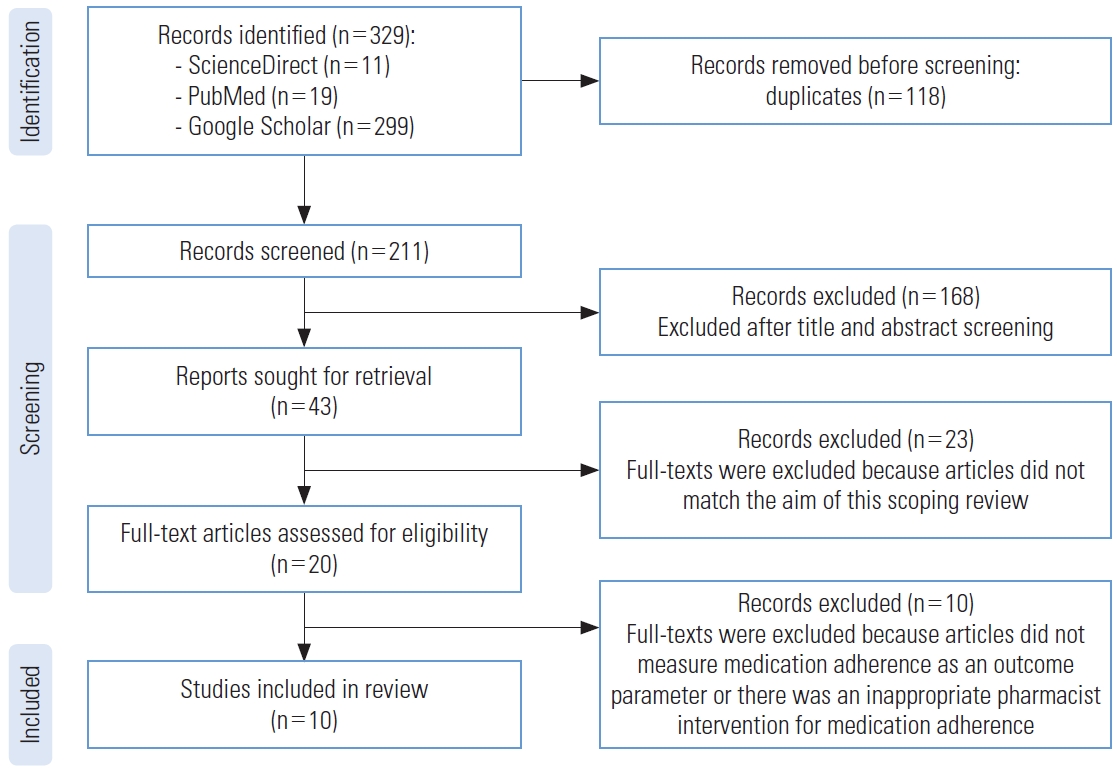

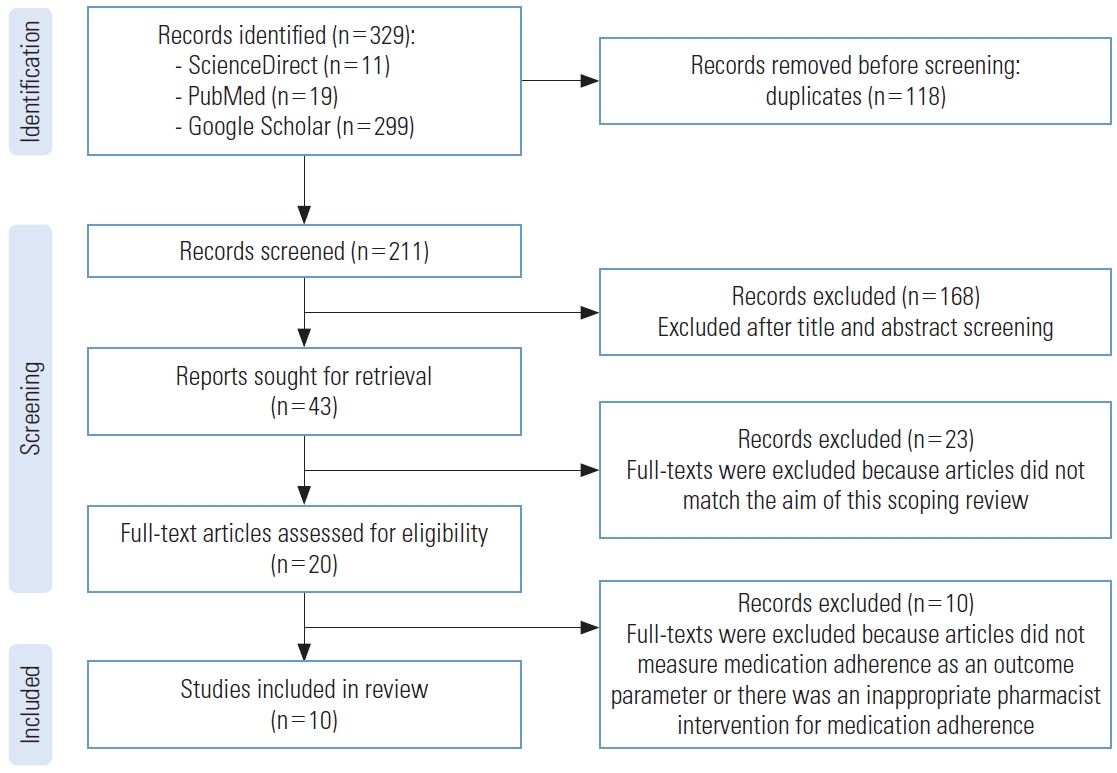

- A scoping literature search was conducted through the ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases. The literature search included all original articles published in English until August 2023 for which the full text was available. This scoping review was carried out by a team consisting of pharmacists and neurologists following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews and the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines, including 5 steps: identifying research questions, finding relevant articles, selecting articles, presenting data, and compiling the results.

-

Results:

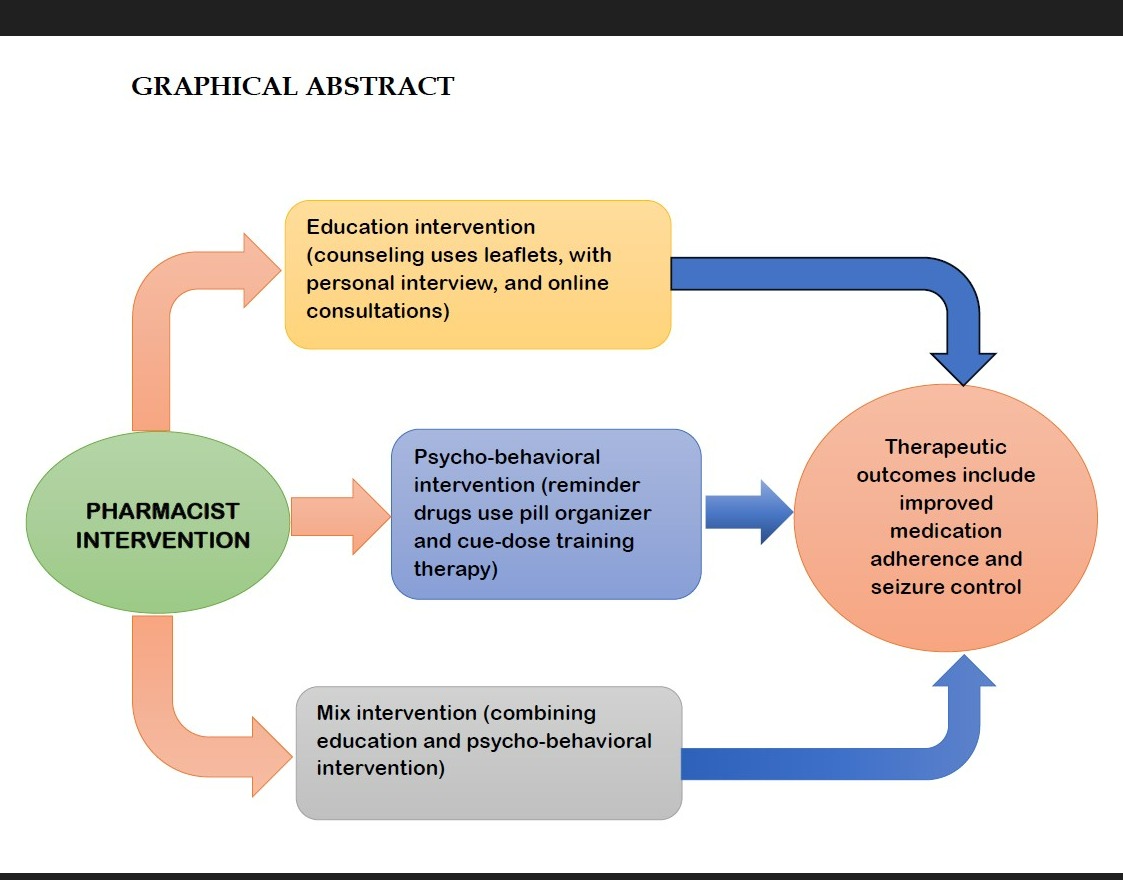

- The literature search yielded 10 studies that discussed pharmacist interventions for patients with epilepsy. Five articles described educational interventions involving drug-related counseling with pharmacists. Two articles focused on similar pharmacist interventions through patient education, both verbal and written. Three articles discussed an epilepsy review service, a multidisciplinary intervention program involving pharmacists and other health workers, and a mixed intervention combining education and training with therapy-based behavioral interventions.

-

Conclusions:

- Pharmacist interventions have been shown to be effective in improving medication adherence in patients with epilepsy. Furthermore, these interventions play a crucial role in improving other therapeutic outcomes, including patients’ knowledge of self-management, perceptions of illness, the efficacy of antiepileptic drugs in controlling seizures, and overall quality of life.

- Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by the occurrence of unprovoked seizures [1]. These seizures are recurrent and result from excessive and abnormal neuronal activity in the brain, which can be caused by various factors including head trauma, stroke, or metabolic disorders [2]. According to data from the World Health Organization, it is estimated that 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, and 70% of them could be seizure-free with proper diagnosis and treatment [3]. However, the prevalence of treatment failure is still significant, as demonstrated by the results of the Standard and New Antiepileptic Drugs trial, which reported a 29% rate of antiepileptic medication failure among patients with generalized tonic-clonic seizures [4]. Additionally, about 63% of individuals receiving epilepsy treatment show favorable seizure control in response to the prescribed therapy, while 37% experience treatment failure with poor seizure control [5]. To date, poor drug adherence remains a major cause of uncontrolled therapy in patients with epilepsy. Adherence to medication involves patient behavior in taking medication according to the prescriber’s (doctor’s) instructions [6,7]. Non-adherence to medication regimens is a potential risk for the recurrence of epilepsy and is closely linked to a higher incidence of hospitalization and increased financial burdens [8-10].

- Epilepsy treatment is complex and may require multiple antiepileptic drugs, special diets, and neurostimulation [11]. Additionally, the use of antiepileptic drugs often leads to side effects and drug-drug interactions [12,13], which can result in poor patient adherence, especially among those with limited knowledge about the disease and its treatment [14]. Given these challenges, the role of pharmacists is crucial in providing education and counseling [15]. Pharmacists have demonstrated their ability to enhance medication adherence among epilepsy patients [16]. According to a systematic review by Reis et al. [17], pharmacists can positively impact epilepsy patients by increasing adherence to antiepileptic drugs, enhancing knowledge about epilepsy, and improving patients’ quality of life. One strategy of the American Epilepsy Society for managing epilepsy is to integrate pharmacists who can collaborate with other health workers to improve access to health services [18]. However, there is limited information on how pharmacists specifically contribute to increasing patients’ adherence to medication. Therefore, this literature review aims to examine the contribution of pharmacists to improving the clinical outcomes of epilepsy patients, focusing particularly on medication adherence.

INTRODUCTION

- This scoping review was conducted by a team of pharmacists and neurologists in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines [19] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews [20]. The framework for the scoping review, based on the JBI guidelines, comprises 5 stages: identifying research questions, locating relevant articles, selecting articles, presenting data, and summarizing the findings [19]. The study selection process adhered to a flowchart adapted from the PRISMA statement [20].

- Identify Research Questions

- The research question was as follows: how can pharmacists contribute to improving medication adherence in epilepsy patients?

- Find Relevant Research

- We conducted a scoping literature search using the databases ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Google Scholar. The search employed a Boolean combination of terms: (“pharmacist” or “pharmacy”) AND (“intervention”) AND (“epilepsy” or “epileptic”) AND (“adherence” or “compliance”). This search included all original articles published in English up to August 23, 2023, with full texts available. Four authors—IE, ZI, NMY, and IS—implemented a two-step procedure to select relevant articles. Initially, after eliminating duplicates, each author independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of articles that discussed interventions conducted by pharmacists for epilepsy patients, without restricting the type of intervention or study.

- Research Article Selection

- The next step was to read full-text articles that meet the inclusion criteria: (1) interventions conducted by pharmacists or in collaboration with other multidisciplinary health practitioners, (2) studies published in English, (3) no restrictions on the types of interventions provided in the full-text articles, (4) the therapeutic parameters observed included adherence, with or without secondary outcomes such as knowledge, seizure control, or quality of life (Figure 1).

- Data Presentation

- Four authors (IE, ZI, NMY, IS) were responsible for data extraction and presentation from the included studies. The tables record information such as authors, publication year, country, study design, pharmacist interventions, participants involved, outcome parameters, and study results. The data are presented through a qualitative analysis based on the existing data in each article (Table 1) [7,21-29]. Additional details about the type and description of interventions can be found in Table 2 [7,21,22,24,26,27,30-32].

- Results Compilation

- A series of discussions among all reviewers was conducted to refine the best approach for reviewing, summarizing, and presenting the literature findings in a consistent format. The results are organized and summarized based on their relevance to the overall research question.

- Ethics Statement

- As this was a scoping review, data extraction was conducted solely from published articles. Therefore, no institutional review board approval was needed.

METHODS

- A comprehensive search of the ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases yielded a total of 329 entries identified as potentially relevant for the study. After screening to remove duplicates and examining the abstracts of articles used in this scoping review, 43 articles were obtained. Upon reviewing the full-text, we excluded 33 articles due to objectives that did not match and because they did not measure medication adherence as an outcome parameter. The adherence measurements used in the reviewed articles included not only questionnaires but also blood drug levels (Figure 1).

- This scoping review examines all publications that involve interventions by pharmacists or pharmacy students in treating patients with epilepsy. The contributions of pharmacists identified in the studies include providing counseling (verbal, written, and online consultations), as well as setting schedules and reminders for medication adherence [7,22,25,27-29]. Additionally, pharmacists may distribute informational leaflets to patients as part of their clinical practice [24]. Educational interventions through counseling are often paired with strategies to improve adherence to drug regimens, such as modifying drug schedules to simplify medication intake [22]. Pharmacist interventions also encompass education through personal consultations, which cover understanding the disease (patient’s condition), drug use (adherence, benefits, administration methods, preparation, drug interactions, procedures for reporting side effects, seizures, and how to contact a clinician if issues arise during treatment) [23,25]. As health professionals, pharmacists collaborate with other healthcare providers in multidisciplinary programs to offer insights into epilepsy medications and therapies for comorbid conditions (Table 1) [26]. Moreover, collaboration between pharmacists and other multidisciplinary professionals is not limited to healthcare workers but can also include educators. Research by Yilmazel [33] indicates that there is generally low awareness of epilepsy, negative attitudes towards the condition, and limited health literacy among teachers and students. This highlights an opportunity for pharmacists to partner with teachers to enhance epilepsy awareness through activities such as workshops, panels, and health education training on epilepsy.

RESULTS

- Epilepsy is a chronic condition that requires long-term treatment. The administration of antiepileptic drugs typically starts with a monotherapy at the lowest possible dose, which may be increased to achieve effective levels while minimizing side effects. If seizures continue, a combination of antiepileptic drugs may be required [34]. In this context, pharmacists play a crucial role by reviewing patient medications, conducting drug reconciliations, analyzing adverse events, and implementing interventions to enhance treatment outcomes [35]. According to ten reviewed studies, pharmacist interventions are designed to improve drug adherence through either direct or face-to-face counseling, or via digital services [26]. Direct counseling involves providing patients with detailed information about epilepsy symptoms, seizure triggers, antiepileptic drugs, medication adherence, and the effectiveness of these drugs in controlling seizures [7,21,24,27,29]. Additionally, printed leaflets containing information about epilepsy treatment can be distributed to the patient’s caregiver [24]. Moreover, Tang et al. [22] implemented an educational intervention that combined direct face-to-face counseling with a behavioral strategy by providing a medication-taking schedule. This intervention included a modified medication schedule presented in a table format, which illustrated the daily therapy regimen with pictures of the antiepileptic drugs and cues to remind patients to take their medication. This approach helps patients better understand their treatment regimen and prevents them from missing doses. Lastly, Zheng et al. [26] explored the effects of comprehensive counseling provided by multidisciplinary health worker teams.

- According to the reviewed studies, interventions conducted by pharmacists have played a crucial role in improving patient health outcomes, particularly in enhancing medication adherence. Research conducted by AlAjmi et al. [7], Fogg et al. [21], Chandrasekhar et al. [27], Jarad et al. [28], and Tamilselvan et al. [29] demonstrates that educational interventions, either through direct verbal counseling or structured 30-minute faceto-face interviews, can significantly increase adherence to medication regimens and strengthen patients’ belief in their treatment (Table 1). Additionally, studies by AlAjmi et al. [7] and Jarad et al. [28] indicated a significant difference in drug adherence between control and intervention groups. Another effective counseling method, providing leaflets, has proven particularly beneficial for caregivers of pediatric epilepsy patients [24]. In the realm of pharmaceutical care, counseling is crucial for enhancing the quality of life among epilepsy patients [36]. The goal of educational interventions is to bolster patient knowledge about the disease and treatment, as well as to alter patient beliefs or perceptions about their treatment, as assessed by a questionnaire. Such education helps reduce patients’ fear of the stigma associated with seizures and enhances their ability to self-manage epilepsy [36]. Educational interventions can be administered by pharmacists or other healthcare professionals, such as doctors. Li et al. [23] developed a program known as the Epilepsy Review Service, which provided comprehensive information about the disease, including the types of seizures, their duration, triggers, and potential side effects. The service also included a therapeutic drug monitoring service, which served as a reference for dose adjustments by prescribing doctors and helps prevent drug toxicity.

- Interventions for epilepsy patients can also be administered by a multidisciplinary team of health workers, including pharmacists, neurologists, and nurses. These professionals are expected to deliver integrated and comprehensive information and services tailored to their specific areas of expertise [26]. Such interventions have been shown to significantly enhance medication adherence and quality of life, as measured by the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) and the 31-item Quality of Life in Epilepsy questionnaires, respectively. Moreover, Tang et al. [22] reported that educational interventions (both verbal counseling and written materials) combined with behavioral changes, such as the use of medication reminders, significantly improved medication adherence and seizure control. Patients were prompted to take their medication through the use of illustrated tables that outlined their daily therapy schedules. However, there was no significant difference in outcomes between the control group, which received only educational interventions, and the intervention group, which received both educational and behavioral interventions (Table 2). Behavioral interventions, or skill-based psychological strategies, are implemented to modify behavior. They require practice and understanding to effectively change habits and enhance quality of life [37]. Furthermore, improving patient self-management or self-efficacy in their treatment can lead to greater therapy success, foster adaptation to chronic disease treatment patterns, and directly impact the patient’s quality of life [38].

- Adherence to taking medication refers to the extent to which a patient follows the prescriber’s instructions when using medication [6]. Research has shown that adherence to antiepileptic drug therapy can prevent seizures or even achieve seizure freedom in up to 70% of cases [39]. A study by Niriayo et al. [40] found that epilepsy patients with low medication adherence were eleven times more likely to experience uncontrolled seizures compared to those with high medication adherence. Adherence to treatment can be measured directly or indirectly [16]. Direct methods include measuring drug levels in hair or body fluids such as blood or saliva. Indirect methods, in contrast, utilize non-biological tools, including self-reported pill counts, appointment attendance, medication refills, questionnaires, and seizure frequency [41]. Questionnaires are commonly used as indirect measures to assess drug adherence outcomes, including the MMAS-8, MMAS-4 [22,26-28], the Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire [25], and the Medication Adherence Report Scale [21].

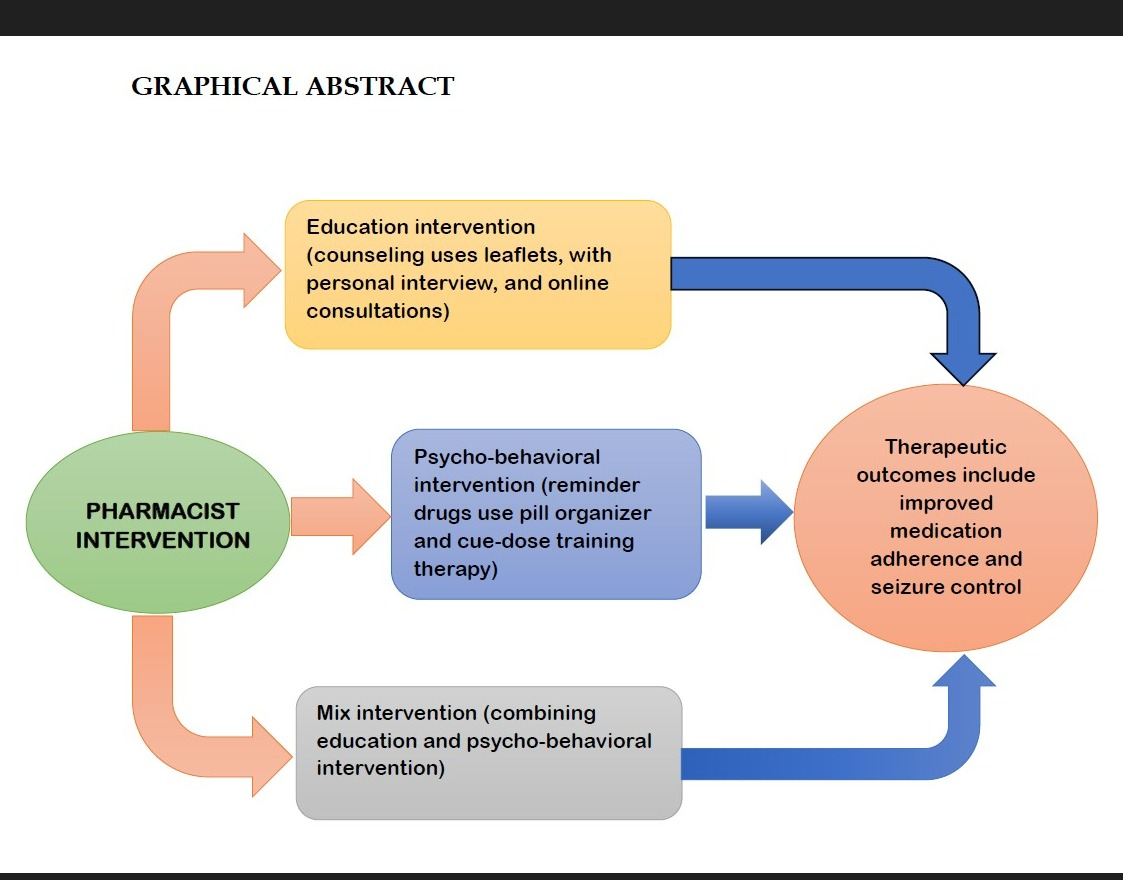

- This scoping review indicates that pharmacists can improve medication adherence and impact other parameters, such as seizure control and quality of life for epilepsy patients, through three types of interventions: educational, psycho-behavioral, and mixed interventions (Table 2). This aligns with findings from a review by Al-Aqeel et al. [32], which suggests that adherence can be increased through these three intervention methods. However, this scoping review has limitations, including only reviewing articles published in English and the need for a broader literature search across more databases. Another limitation is the narrow inclusion criteria related to outcome parameters, as the criteria for this review are limited to pharmaceutical interventions concerning drug use adherence (medication adherence). Future reviews could explore pharmacist interventions on epilepsy awareness, potentially involving other health workers or social workers.

DISCUSSION

- Pharmacist interventions have been shown to be effective in improving medication adherence among epilepsy patients. Direct counseling, provided either through face-to-face interactions or digital services, equips patients with essential information about their condition and insights into epilepsy symptoms, seizure triggers, and antiepileptic drugs. Additionally, distributing educational materials like leaflets can be particularly helpful for caregivers of pediatric epilepsy patients. Multidisciplinary interventions that include pharmacists, neurologists, and nurses offer comprehensive care that can improve both drug adherence and the quality of life for epilepsy patients. Furthermore, behavioral interventions, such as medication reminders and skill-based psychological support, can significantly boost medication adherence and seizure control. Overall, pharmacist interventions are crucial in optimizing therapy outcomes, which include increased knowledge of self-management, improved perception of illness, enhanced effectiveness of antiepileptic drugs in controlling seizures, and better quality of life.

CONCLUSION

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

-

Funding

This work was supported by the Indonesian Endowment Funds for Education (LPDP) and the Center for Higher Education Funding (BPPT) (No. 202209091837) for financial support for education and research dissertations.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ernawati I, Ikawati Z, Yasin NM, Setyopranoto I. Data curation: Ernawati I, Ikawati Z, Yasin NM, Setyopranoto I. Funding acquisition: Ernawati I. Methodology: Ernawati I, Ikawati Z, Yasin NM, Setyopranoto I. Writing – original draft: Ernawati I, Ikawati Z, Yasin NM, Setyopranoto I. Writing – review & editing: Ernawati I, Ikawati Z, Yasin NM, Setyopranoto I.

Notes

Acknowledgements

| No | Study (country of origin of the study) | Study design | Pharmacist intervention | Participants involved | Outcome parameter measurements | Results of the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fogg et al., 2012 [21] (UK) | One-arm interventional study | PLEC | A total of 106 patients participated; Of these, 82 received PLEC, but only 50 patients completed the intervention thoroughly | Self-reported medication adherence using the MARS | Medication adherence increased significantly (p = 0.030); |

| Participants in the clinic received a 30-min consultation with a practice-based pharmacist; The pharmacist allows patients with epilepsy to ask questions about their medication | Epilepsy-related quality of life using the QOLIE-10 | Quality of life (QOLIE score post-PLEC) improved significantly (p = 0.049); | ||||

| General psychological well-being via the GHQ-12, a 12-item questionnaire | The total GHQ-12 score also improved significantly (p = 0.009, Wilcoxon matched pairs) | |||||

| 2 | Tang et al., 2014 [22] (China) | RCT with 2 groups: group I (control) received an educational intervention, and group II received both educational and behavioral interventions | Education and behavioral interventions | A total of 109 patients with epilepsy were randomized into 2 groups | Adherence using the MMAS-4 | There was a statistically significant difference between the baseline and follow-up levels of adherence (p<0.001), as well as seizures (p<0.001) |

| Education intervention (written and oral instruction); A pharmacist provided patient education and counseling in accordance with the criteria of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists | Frequency of seizures | Knowledge score (p<0.00) | ||||

| Understanding of AED information (the 5 items tested in the questionnaire were the name of the AED, dosage, length of AED use, how to deal with adverse drug responses, and missed pills) | However, no statistically significant difference (p>0.05) existed between the intervention and control groups | |||||

| The cue-dose training therapy-based behavioral intervention included a modified drug schedule | Adherence increased (p = 0.827) | |||||

| Control of seizures (p = 0.988) | ||||||

| (31-item) QOLIE-31 | Knowledge improvement (p = 0.231) | |||||

| Overall quality of life (p = 0.947) | ||||||

| 3 | AlAjmi et al., 2017 [7] (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) | Quasi-experimental study with 2 groups (control and intervention) | An educational interview with a pharmacist (30-min structured verbal face-to-face interview) | After 6 wk, only 29 patients in the control group and 27 patients in the intervention group had completed the adherence measurement | Medication adherence using MMAS-8 | The intervention group had statistically significant differences between before and after the intervention (p<0.001) |

| Education on the medical aspects of epilepsy, as well as information on AEDs; Education materials such as instructional pharmacy interviews, brochures, or pill organizers were used to deliver information on the medical features of epilepsy in the first portion and information on antiepileptic drugs | The medication adherence score in the control group did not show a statistically significant difference after the second visit (p=0.792) | |||||

| At baseline, there was no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups in adherence scores, but a difference after the intervention was significant (p=0.024) | ||||||

| 4 | Li et al., 2018 [23] (Malaysia) | Quasi-experimental groups | ERS | The no. of respondents was 203, but 156 patients completed the study until the final follow-up | ERS quality (QUIET) | There was an increase in counseling (89.3%), drug-related reviews such as side effects (77.9%), and drug interactions (82.1%) |

| The ERS quality indicator uses QUIET, which has 3 components: a review of the epileptic condition, and individualized epilepsy counseling | Seizure frequency | There was a statistically significant decrease in the number of seizures at the end of follow-up (p<0.001) | ||||

| 5 | Jinil et al., 2018 [24] (India) | One-arm interventional study | Patient counseling | 66 subjects completed the second visit | Medication adherence using MMAS-4 | The no. of patients who had high adherence increased after giving counseling interventions with leaflet designs (from 0.00 to 36.36%) |

| Counseling for pediatric | ||||||

| Patients’ caregivers use leaflets about epilepsy and its treatment | ||||||

| 6 | Ma et al., 2019 [25] (China) | Quasi-experimental study with 2 groups (control and intervention) | Patients/families are served by a pharmacy and receive educational interventions | There were 1031 patients from the intervention hospital, and 1902 valproic acid samples were taken | Medication adherence using the Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire | Adherence to medications increased from 56.0% to 73.9% |

| The pharmacy service and verbal instruction information supplied to patients/families included the following: | ||||||

| (1) Understanding of the epilepsy illness condition; (2) AED treatment (treatment rationale, benefits, drug adherence, and treatment duration); (3) Medication administration (dosing, when to take a dose, storing the medication, and what to do if a dose is missed); (4) Drug interactions or drug-food interactions; (5) Medication side effects and what to do if you experience them; (6) How to properly discontinue or switch medications; (7) Drug concentrations in the laboratory are monitored; (8) How to contact clinicians | There were 1134 patients from the control hospital, and 2441 valproic acid samples were taken | |||||

| 7 | Zheng et al., 2019 [26] (China) | RCT with 2 groups: group I (control) received usual care, and group II received usual care with an additional 12-mo multidisciplinary program | The epilepsy specialist nurse, psychiatrist, and pharmacist give the information about epilepsy | 184 patients with epilepsy from a tertiary hospital in eastern China (92 in the control group and 92 in the intervention group) | Medication adherence using MMAS-8 | Medication adherence (p=0.006) |

| The intervention’s (multidisciplinary program) content included knowledge of epilepsy (the condition itself, its comorbidities, therapies, medication use, and pregnancy-related difficulties), daily self-management skills, and pertinent psychosocial information from a specialist epilepsy nurse, psychiatrist, pharmacist, and members of the multidisciplinary management program; (1) personal interviews; (2) online counseling | Standard of living (QOLIE-31) | A higher overall QOLIE-31 score (p=0.001) | ||||

| The BDI measured the severity of depression | There were fewer patients with severe depression (p=0.013) | |||||

| Anxiety (according to the BAI) | Anxiety (p=0.002) in the intervention group, more patients with moderate-to-high AED use | |||||

| Frequency of seizures | After 12-mo, there was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of patients in the control and intervention groups who had low seizure frequency (p=0.001) | |||||

| 8 | Chandrasekhar et al., 2020 [27] (India) | One-arm interventional study | Patient counseling | 100 epileptic inpatients at a South Indian tertiary care hospital’s neurology department | Medication adherence using the MMAS-4 | According to the study, the total improvement in medication adherence and patient understanding was statistically significant following the intervention; High adherence wa found in 62% of participants, medium adherence in 20%, and low adherence in 18% |

| The counseling intervention included an educational interview involving a 30-min structured verbal face-to-face interview | Believing in medication use belief survey (contained 10 questions, with a 5-point Likert scale used to record the response to each statement strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, and strongly agree) | Medication belief assessment showed statistically significant results (p≤0.05) | ||||

| 9 | Jarad et al., 2022 [28] (Jordan) | RCT with 2 groups: intervention group (received the standard medical care and pharmacist-led educational interview) and control group (only received the standard medical care) | Pharmacist-led clinical education | At the time of the follow-up, 71 patients (36 in the intervention group and 35 in the control group) were included in the statistical analysis | Adherence to medication using the MMAS-8 | At the follow-up, there was a significant difference in medication adherence between the 2 groups (p<0.001) |

| As an intervention group, clinical pharmacist-led education was used | Safety using the Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality Score | There was no significant difference between groups in terms of effectiveness (p>0.05) or safety (p = 0.08) at follow-up | ||||

| In addition to routine medical care, the first group had a 30-min educational conversation with the parent/caregiver led by a clinical pharmacist; The control group was given only standard medication care | Parent/caregiver satisfaction with AED information was assessed using the Soccer Injury Movement Screen Score | Higher information satisfaction (p<0.001) | ||||

| The Paediatric Quality of Life Epilepsy Module Score was used to assess quality of life in pediatric patients with epilepsy | The intervention group had higher quality of life (p = 0.05) | |||||

| 10 | Tamilselvan et al., 2022 [29] (India) | One-arm interventional study | Patient counseling (no detailed explanation of the form and counseling material provided) | The total no. of respondents was 150, but only 109 patients completed the study by the end of the follow-up period | Medication adherence was evaluated using the MMAS-8 | Improvement in medication adherence from the mean of MMAS-8 score (standard deviation) in the first and end of follow-up was 4.50 (1.80) and 5.23 (1.29) |

| Quality of life using the QOLIE-31 (version 1.0) questionnaire | The educational group exhibited a positive correlation with all the subscales of QOLIE-31 |

PLEC, pharmacist-led epilepsy consultations; MARS, Medication Adherence Rating Scale; QOLIE, quality of life in epilepsy; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; RCT, randomized controlled trial; MMAS, Morisky Medication Adherence Scale; AED, antiepileptic drug; ERS, Epilepsy Review Service; QUIET, Quality Indicator in Epilepsy Treatment; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory.

| Type of intervention | Pharmacist contribution | Description of the intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Education intervention | Pharmacist counseling about epilepsy uses leaflets (written instructions), personal interviews (face-to-face consultation), and online counseling [7,21,24,26,27] | An educational intervention can be provided by pharmacists or other health workers such as doctors; An educational intervention including explanations of medication use, discussions of the importance of adherence, and information about the effects of non-adherence and problems related to medication management can increase adherence to medication use [30] |

| Psycho-behavioral/behavioral intervention | Pharmacists can use drug reminders (use pill organizers) [7] | A behavioral intervention or skills-based psychological intervention is another intervention that is carried out to change behavior and requires practice and understanding so that it can produce various physiologic changes [31]; Psycho-behavioral interventions, based on the theory of psychotherapy, include behavioral, cognitive behavioral, and mind-body treatments; Behavioral interventions and self-management may improve the quality of life and health-related emotional well-being of adults and adolescents with epilepsy [31] |

| Cue dose training therapy to remind patients about their drug schedule [22] | ||

| Mixed/combination intervention | An education intervention has been combined with a behavioral intervention in a modified medication schedule, which was presented in the form of a table that illustrated the daily medication therapy of participants with pictures of antiepileptic drugs, along with cues to take their medication [22] | Pharmacists combine patient education (written or oral instructions) with a behavioral intervention [32] |

- 1. Wirrell EC. Classification of seizures and the epilepsies. In: Cascino GD, Sirven JI, Tatum WO, editors. Epilepsy. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2021. p. 11-22 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119431893.ch2

- 2. Aminoff M, dan Douglas V. Nervous system disorders. In: Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, editors. Current medical diagnosis & treatment. New York: McGraw Hill Education; 2022. p. 987-991

- 3. World Health Organization. Epilepsy; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy

- 4. Bonnett LJ, Tudur Smith C, Smith D, Williamson PR, Chadwick D, Marson AG. Time to 12-month remission and treatment failure for generalised and unclassified epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85(6):603-610. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-306040ArticlePubMed

- 5. French JA, Pedley TA. Clinical practice. Initial management of epilepsy. N Engl J Med 2008;359(2):166-176. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp0801738ArticlePubMed

- 6. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action; 2003 [cited 2023 Jul 17]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42682

- 7. AlAjmi R, Al-Aqeel S, Baz S. The impact of a pharmacist-led educational interview on medication adherence of Saudi patients with epilepsy. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11: 959-964. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S124028ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Faught RE, Weiner JR, Guérin A, Cunnington MC, Duh MS. Impact of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs on health care utilization and costs: findings from the RANSOM study. Epilepsia 2009;50(3):501-509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01794.xArticlePubMed

- 9. Lie IA, Hoggen I, Samsonsen C, Brodtkorb E. Treatment nonadherence as a trigger for status epilepticus: an observational, retrospective study based on therapeutic drug monitoring. Epilepsy Res 2015;113: 28-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.03.007ArticlePubMed

- 10. Chen Z, Brodie MJ, Liew D, Kwan P. Treatment outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy treated with established and new antiepileptic drugs: a 30-year longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Neurol 2018;75(3):279-286. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3949ArticlePubMed

- 11. Rohde NN, Baca CB, Van Cott AC, Parko KL, Amuan ME, Pugh MJ. Antiepileptic drug prescribing patterns in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2015;46: 133-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.027ArticlePubMed

- 12. Moseley BD, Chanteux H, Nicolas JM, Laloyaux C, Gidal B, Stockis A. A review of the drug-drug interactions of the antiepileptic drug brivaracetam. Epilepsy Res 2020;163: 106327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106327ArticlePubMed

- 13. Mutanana N, Tsvere M, Chiweshe MK. General side effects and challenges associated with anti-epilepsy medication: a review of related literature. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2020;12(1):e1-e5. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2162Article

- 14. Bacci JL, Zaraa S, Stergachis A, Simic G, White HS. Community pharmacists’ role in caring for people living with epilepsy: a scoping review. Epilepsy Behav 2021;117: 107850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107850ArticlePubMed

- 15. Ratanajamit C, Kaewpibal P, Setthawacharavanich S, Faroongsarng D. Effect of pharmacist participation in the health care team on therapeutic drug monitoring utilization for antiepileptic drugs. J Med Assoc Thai 2009;92(11):1500-1507PubMed

- 16. Ernawati I, Islamiyah WR. How to improve clinical outcome of epileptic seizure control based on medication adherence? A literature review. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2018;6(6):1174-1179. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.235ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Reis TM, Campos M, Nagai MM, Pereira L. Contributions of pharmacists in the treatment of epilepsy: a systematic review. Am J Pharm Benefits 2016;8(3):e55-e60

- 18. Taube M, Kotloski R, Karasov A, Jones JC, Gidal B. Impact of clinical pharmacists on access to care in an epilepsy clinic. Fed Pract 2022;39(Suppl 1):S5-S9. https://doi.org/10.12788/fp.0252ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13(3):141-146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050ArticlePubMed

- 20. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(7):467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850ArticlePubMed

- 21. Fogg A, Staufenberg EF, Small I, Bhattacharya D. An exploratory study of primary care pharmacist-led epilepsy consultations. Int J Pharm Pract 2012;20(5):294-302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00207.xArticlePubMed

- 22. Tang F, Zhu G, Jiao Z, Ma C, Chen N, Wang B. The effects of medication education and behavioral intervention on Chinese patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2014;37: 157-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.05.017ArticlePubMed

- 23. Li WS, Ye CC, Sulaiman N, Rahman HM, Mun NK. The impact of epilepsy review service on seizure control in primary care. Pharm Res Rep 2018;1: 32-41

- 24. Jinil AL, Bharathi DR, Nataraj GR, Daniel M. Impact of counseling on patient caretaker’s knowledge and medication adherence to paediatric antiepileptic drug therapy. Int J Sci Healthc Res 2018;3(4):158-165

- 25. Ma M, Peng Q, Gu X, Hu Y, Sun S, Sheng Y, et al. Pharmacist impact on adherence of valproic acid therapy in pediatric patients with epilepsy using active education techniques. Epilepsy Behav 2019;98(Pt A):14-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.06.003ArticlePubMed

- 26. Zheng Y, Ding X, Guo Y, Chen Q, Wang W, Zheng Y, et al. Multidisciplinary management improves anxiety, depression, medication adherence, and quality of life among patients with epilepsy in eastern China: a prospective study. Epilepsy Behav 2019;100(Pt A):106400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.07.001ArticlePubMed

- 27. Chandrasekhar D, Mohanlal SP, Mathew AC, Hashik PM. Impact of clinical pharmacist managed patient counselling on the knowledge and adherence to antiepileptic drug therapy. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2020;8(4):1242-1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2020.04.021Article

- 28. Jarad S, Akour A, Khreisat WH, Elshammari AK, Madae’en S. The role of clinical pharmacist in pediatrics’ adherence to antiepileptic drugs. J Pharm Technol 2022;38(5):272-282. https://doi.org/10.1177/87551225221097619ArticlePubMedPMC

- 29. Tamilselvan T, Menon AG, Vijayan AS, Pradosh A, Thomas H. Impact of pharmacist assisted patient counselling in improving medication adherence and quality of life in epileptic patients. Sch J App Med Sci 2022;10(6):1012-1015. https://doi.org/10.36347/sjams.2022.v10i06.023Article

- 30. Özdağ E, Fırat O, Çoban Taşkın A, Uludağ İF, Şener U, Demirkan K. Pharmacist’s impact on medication adherence and drugrelated problems in patients with epilepsy. Turk J Pharm Sci 2024;20(6):361-367. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjps.galenos.2023.36080ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Haut SR, Gursky JM, Privitera M. Behavioral interventions in epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol 2019;32(2):227-236. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000000661ArticlePubMed

- 32. Al-Aqeel S, Gershuni O, Al-Sabhan J, Hiligsmann M. Strategies for improving adherence to antiepileptic drug treatment in people with epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;10(10):CD008312. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008312.pub4ArticlePubMed

- 33. Yilmazel G. Teachers’ negative attitudes and limited health literacy levels as risks for low awareness of epilepsy in Turkey. J Prev Med Public Health 2023;56(6):573-582. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.23.330ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Boon P, Ferrao Santos S, Jansen AC, Lagae L, Legros B, Weckhuysen S. Recommendations for the treatment of epilepsy in adult and pediatric patients in Belgium: 2020 update. Acta Neurol Belg 2021;121(1):241-257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-020-01488-yArticlePubMed

- 35. Marawar R, Faraj M, Lucas K, Burns CV, Garwood CL. Implementation of an older adult epilepsy clinic utilizing pharmacist services. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2021;61(6):e93-e98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.07.003Article

- 36. Eshiet UI, Okonta JM, Ukwe CV. Impact of a pharmacist-led education and counseling interventions on quality of life in epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsy Res 2021;174: 106648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2021.106648ArticlePubMed

- 37. Michaelis R, Tang V, Wagner JL, Modi AC, LaFrance WC Jr, Goldstein LH, et al. Psychological treatments for people with epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;10(10):CD012081. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012081.pub2ArticlePubMed

- 38. Pandey DK, Levy J, Serafini A, Habibi M, Song W, Shafer PO, et al. Self-management skills and behaviors, self-efficacy, and quality of life in people with epilepsy from underserved populations. Epilepsy Behav 2019;98(Pt A):258-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.07.042ArticlePubMed

- 39. Belayneh Z, Mekuriaw B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of anti-epileptic medication non-adherence among people with epilepsy in Ethiopia. Arch Public Health 2020;78: 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00405-2ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Niriayo YL, Mamo A, Kassa TD, Asgedom SW, Atey TM, Gidey K, et al. Treatment outcome and associated factors among patients with epilepsy. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):17354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35906-2ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Paschal AM, Hawley SR, St Romain T, Ablah E. Measures of adherence to epilepsy treatment: review of present practices and recommendations for future directions. Epilepsia 2008;49(7):1115-1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01645.xArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

KSPM

KSPM

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite